A life dedicated to helping children

HIV is the infection that defined the late 20th century, says paediatrician Prof Mark Cotton – a clinician and researcher who has been helping shape, strengthen and define care for HIV patients, especially children.

His world-class expertise in this regard was yet again acknowledged in 2022 when he received another A1-rating from the National Research Foundation.

In 2021, Cotton retired as a distinguished professor and head of the Division of Paediatric Infectious Diseases in Stellenbosch University’s (SU’s) Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. At the end of 2022, he also passed on the baton as director of the Family Centre for Research with Ubuntu (FAMCRU), which he established in the early 2000s.

He describes himself first and foremost as a clinician with keen observational skills – one that has a knack for statistics, number-crunching and keeping things together.

During his career of 40 years, Cotton was one of the first doctors in Africa to treat children with antiretrovirals (ARVs). Global health policy was often rewritten thanks to the large-scale trials he contributed to.

The CHER trial

Cotton’s involvement as co-principal investigator of the Children with HIV Early Antiretroviral Therapy (CHER) trial was a career highlight. The trial was funded by the USA’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Its findings demonstrated how important it is to rapidly identify young infants who have HIV, to start them on ARV treatment as soon as possible thereafter, and have it used continuously for years.

Cotton had the honour of presenting the trial’s findings to the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, on behalf of the entire research team.

“Even before we had published on it, the WHO changed their guidelines so that ARVs could be given to children soon after they are diagnosed. This was later also extended to adults,” he says proudly.

He knows this has since saved many lives and spared much suffering.

“Children really led the way.”

A career of influence

Cotton, the previous president of the World Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases (WSPID), is also a WHO advisor on matters related to HIV-positive children, TB co-treatment, HIV and TB prevention, and antiretroviral guidelines.

He was a founder board member of the Collaborative Initiative for Paediatric HIV Education and Research (CIPHER), funded by the International AIDS Society to do HIV-related research on children from resource-limited settings. For years, he also helped edit the eminent Journal of the International AIDS Society (JIAS) and Frontiers in Infectious Diseases.

Cotton was a board member of the South African Medical Council and established the curriculum on infectious diseases that is used by the College of Medicine of South Africa. He was the founder president of both the Southern African Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (SASPID) and the African Society of Paediatric Infectious Diseases (AfPIDS).

Cotton ascribes these positions and achievements to timing, teamwork and the professional relationships that he built up over decades.

“As a stand-alone researcher, I cannot do anything. Being in a team where people get on and are committed to working in a specific area is one of the best things ever.”

The early years

Cotton was raised in Goodwood, Cape Town, where his father worked as a pharmacist “who worshipped medicine”.

He qualified as a doctor from the University of Cape Town in 1979 – a time when no one yet knew about the existence of HIV. His first clinical experience of working with “kiddies” was as a student, at the old Somerset Hospital in Cape Town.

“I really just liked the kids, their enthusiasm and innocence. They tended to get better more quickly [than adults]. It was generally a very positive experience. Working with children was a way to make a positive impact on families.

“I also liked how my lecturers brought science into the treatment of children, applied it to make a diagnosis and did something that was rational and made sense.”

Cotton’s interest in research grew during his registrar years at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) in the mid-1980s. He was working in what is now the Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital and Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital in Johannesburg. He was impressed by how senior clinicians used their observational skills to generate data about specific patients, and refined it into case studies that were valuable to other health practitioners.

His first foray into practical research was made possible by one of his many mentors, Prof Alan Rothberg of Wits. He suggested that Cotton conduct a double-blind cross-over trial to test whether Ritalin medication really helped children with perceived attention problems.

“The results caused lots of controversy,” he says in reference to his finding that children on Ritalin exhibited more attention problems than those given a placebo.

Wits paediatrician Prof Frank Berkowitz, one of the first South African researchers to receive training in infectious diseases abroad, inspired Cotton to research hospital-acquired infections in children. At that stage, this topic had not yet been studied in Africa.

Cotton and Berkowitz were the first researchers to describe a candida (yeast) infection at a so-called ‘drip site’ (i.e., a place where a drip is inserted into the body) in a premature baby, in a paper in 1988. Cotton was also the first to prove that it is safer to give premature babies antifungal therapy orally than intravenously.

At the time, HIV was emerging as an unstoppable, untreatable infection. Cotton received a fellowship to study HIV and other infectious diseases in children in Denver in the USA, where Berkowitz had previously studied.

“My goal was to come back and apply what I had learnt. I was interested in the science, did benchwork in an immunology lab and tried to make it all clinically relevant.”

And that he did.

Cotton and his family returned to Cape Town in 1996, when he started working at SU and Tygerberg Hospital.

He clearly remembers the frustrating HIV-denialism years in South Africa: “The unfolding of HIV was a big problem. There was nothing that one could do for the kiddies. Starting a clinic was difficult. There wasn’t space or money, and we weren’t allowed to use antiretrovirals.”

As such, he joined forces with many other South Africans who have subsequently, like him, all become world leaders in HIV research. Together, they conducted some of the first large-scale HIV trials in South Africa by South Africans, thanks to significant funding from NIAID.

Into the future

Although he has scaled down considerably, Cotton is today still involved in planning and executing trials via FAMCRU. Among these trials are TB vaccine and therapeutic HIV vaccine studies. The latter could, in theory, eventually make it unnecessary for HIV-positive people to use ARVs on a daily basis.

“Through ongoing research in South Africa and worldwide, great strides have been made in HIV treatment, even though a vaccine is not yet on the cards. All of the infrastructure and medicines are now available, comprehensively so.

“When kids with HIV are identified early and they take the medicines, they do amazingly well. That’s actually the best thing.

“ARVs and the fact that more mothers are being protected in pregnancy have made a huge difference.

“In the past, we used to do very big studies, and now we struggle to find enough people to take part in some. Instead of 30 000 babies [per year] being born with HIV, there are now about 1 000 across the country. It is more complex and difficult to manage, but there are far, far fewer cases.

“I never thought I would see it.”

He realises, however, that the job is not yet finished. “The next big challenge is the same as the one we had with the COVID antivaxxers: How do we influence people’s beliefs and practices?

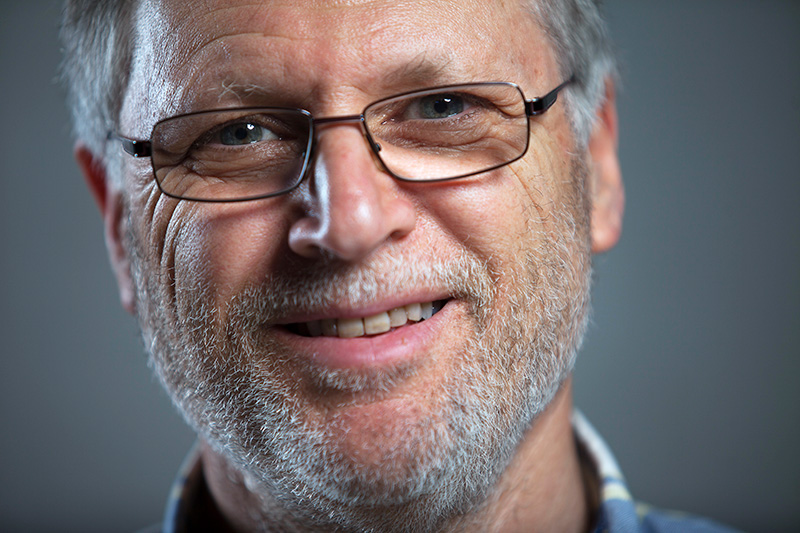

Prof Mark Cotton

Photo by Damien Schumann

Written by Engela Duvenage