A peek at penguins’ posture

Engela Duvenage

Nowadays, when Roanné Coetzer (24) looks at a black and white African penguin, she sees coloured dots.

This is because penguins have been keeping this MEng student very busy during her studies. She has been using her knowledge of deep neural networks and other data science skills to write a computer program that automatically detects African penguin behaviour caught on camera. Her work supports the conservation of this critically endangered seabird, the only species of penguin found along the South African coastline.

At its core, her project is about studying animal behaviour with the help of as much computer capability as possible. Interestingly, this high-tech project started on a very low-tech scale.

The first step was for Coetzer to watch 100 videos of penguins waddling about in order to assign a range of coloured dots to their beaks, flippers, feet and other key movement points on their bodies.

Only then could she start writing an algorithm that helps to ensure that the initial manual phase of assigning key points is, in future, done automatically whenever more footage is fed into her program.

Next, she wrote another algorithm to teach the program to learn and automatically recognise certain types of penguin behaviour, and classify them. These behaviour types include braying, cleaning and aggression towards other birds.

According to Coetzer, the application of machine learning and artificial intelligence to the domain of ecology is gaining ground in a bid to help save the planet and its species.

Her work forms part of a larger project being conducted by the Data Science for Eco-Systems (DS4ES) research group in Stellenbosch University’s (SU’s) School for Data Science and Computational Thinking, led by Dr Emmanuel Dufourq. The project involves, among others, Prof Kanshukan Rajaratnam (director of the school) and Prof Francesco Petruccione, a professor in quantum computing at SU and interim director of the National Institute for Theoretical and Computational Sciences (NITheCS).

Coetzer is following SU’s MEng (Industrial Engineering) structured programme with a focus on data science, a recent future-driven addition to the University’s programme offering. In December 2022, she will be one of the very first students to graduate from this programme.

The use of computers to study animal behaviour builds on pioneering work done in the field of human posture. It has since allowed zoologists and ecologists to more quickly and more easily gain an understanding of the behaviour of animals such as mice and cheetahs, all through means of software that automatically detects and analyses animal behaviour captured on video.

“Coetzer’s work is unique – no one has yet done similar work on penguins or other seabirds,” says her supervisor, Dufourq.

Coetzer’s algorithm can already, at least 80% of the time, automatically and correctly code the movement types captured in a video recording of a single penguin. When broadening the range to include up to three penguins appearing together on screen, her algorithm has an average accuracy rate of 70%.

“The value of this work lies in the foundation it provides for the design, development, and implementation of a passive monitoring system, as well as its time-saving benefits.”

By computerising the process of analysing animals appearing on camera, she ultimately wants to save time for others working in the field of conservation ecology who would otherwise have to manually code each action.

In theory, this computer analysis can now be performed on any footage of African penguins ever filmed – something of which there must be vast volumes, ranging from tourists’ cell phone footage to professional documentary makers’ reels.

Footage shot at the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town and at uShaka Marine World in Durban form the basis of Coetzer’s project, which was undertaken in collaboration with Dr Anna Bastian and MSc student Tenita Padayachee from the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Dufourq explains their choice of footage: “Even in the case of animals in captivity, there are interesting questions to be asked about their behaviour. For example, among African penguins, is there a dominant penguin, and does their behaviour change once the tourists leave and there’s no one around watching them in their home?”

Dufourq’s DS4ES team is building upon Coetzer’s ideas to make them more robust. Soon, they want to mount cameras around the penguin pen at the Two Oceans Aquarium and, for a full year, record the seabirds as they go about their day. Ideally, their behaviour will be analysed in real time.

He believes Coetzer’s penguin work is transferable to work on other animals. “You’d simply need some pictures, do some manual work, and then add these elements to the algorithm.”

The DS4ES’s African penguin project forms part of a larger, ongoing collaborative study on passive acoustic monitoring, led by evolutionary biologist Dr Anna Bastian of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Dr Sara Beery, and Dr Lorène Jeantet. Beery is an assistant professor in the artificial intelligence and decision-making unit of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (MIT EECS) and in the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (MIT CSAIL). She is also a visiting researcher at Google. Jeantet is a postdoctoral researcher at the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences and at SU.

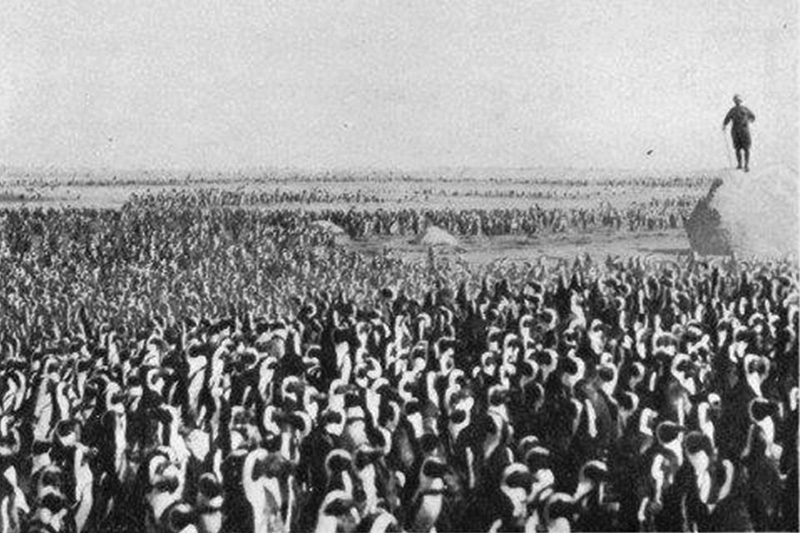

Dassen Island, 1900 | Photo by Cherry Keaton

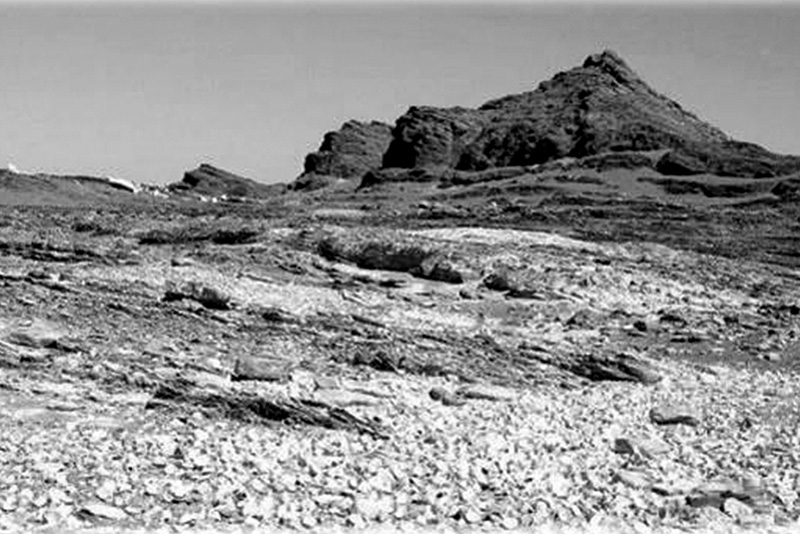

Dassen Island, 2014 | Photo by Christina Hagen

Halifax Island, 1930s | Photo provided by the Eberlanz Museum

Halifax Island, 2004 | Photo by Jessica Kemper