Cape Colony economic history project most extensive of its kind

Willem de Vries

How was wealth created in the Cape region of South Africa during the time it was governed by the Dutch East India Company (VOC)?

For the past seven years, this has been a central research question posed by the economic historians of the Cape of Good Hope Panel, the flagship project of the Laboratory for the Economics of Africa’s Past (LEAP). This laboratory, hosted at Stellenbosch University (SU), focuses on the quantitative study of African economic and social history. It is the result of a growing international focus on economic history since the 2000s.

The Cape Panel, funded until 2026, studies the development of the VOC’s maritime service station in the Cape of Good Hope, as well as the region’s economic growth in the ensuing years.

Prof Johan Fourie, coordinator of LEAP and its programmes, says the initial Cape Panel project flowed naturally from the research he conducted for his PhD degree on the nature, causes, and distribution of wealth in the Cape Colony between 1652 and 1795. He defended his dissertation in 2012 at the University of Utrecht. In 2015, on grounds of his doctoral research, he was announced as winner in the early-modern history category at the International Economic History Congress held in Kyoto. In the same year, he began collaborating with Prof Erik Green of Lund University in Sweden on what would later become known as the Cape Panel.

Even though the initial project had little funding, it already showed potential. As a result, LEAP applied for and received funding from, among others, the Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation. The grant of approximately R51,84 million (SEK 29,4 million) is, to date, the largest amount awarded to a project of this nature in Sweden.

Prof Johan Fourie

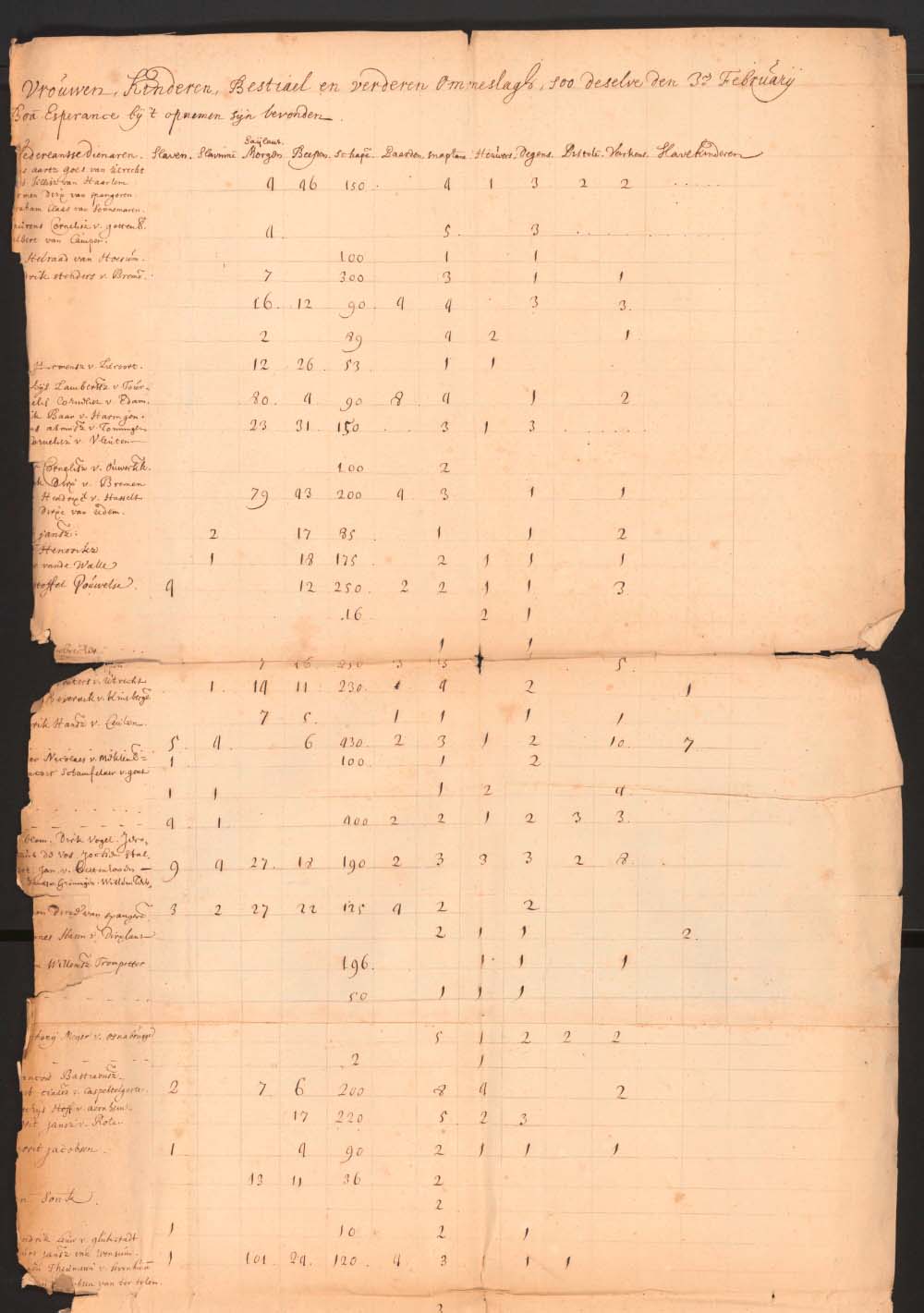

An excerpt of one of the VOC's tax records, known as an "opgaafrol". These records are kept in The National Archives (Nationaal Archief) of the Netherlands.

Tax returns reveal colonial history

For the purposes of this project, researchers have been focusing on the annual tax censuses that the authorities in the Cape collected between the 17th and 19th centuries. The archival documents that the researchers study and transcribe are kept in the Cape Archives in Cape Town and in the National Archives in the Netherlands. The latter also offers access to digital sources.

Funding has made it possible for LEAP to, for the first time ever, transcribe the VOC’s complete tax censuses for their time at the Cape. As a result, the Cape Panel constitutes a dataset documenting a complete settler population over a period of more than 150 years – the largest such dataset in the world, tracking multiple generations.

“Colonial tax records provide a census of sorts of the settler population in each year,” Fourie explains. “The first of these dates from the late 1650s and covers only the Cape. Thereafter, in the 1680s, Stellenbosch was added. The last record for Stellenbosch is from 1844. So, these archives offer records of 160-odd years, a really long time for documentation of this nature.” Apart from settler numbers, the tax documents also provide insight into the economy of the settler population and that of the indigenous Khoesan population at the time.

By using machine learning and other technical tools and techniques of the digital humanities, the researchers involved have gained previously unprecedented access to data that reveals a more detailed account of the economic development of South Africa at the time (1652–1795). They have also created a foundation for future research in the form of an extensive web of references.

Given the extensive nature of the project, LEAP utilises the expertise of academics across subject areas, thereby broadening the base of their empirical work. “The interdisciplinary nature of our projects makes this kind of investigation possible.”

Fourie says the researchers of the Cape Panel will eventually have all the annual census data on the Cape’s settler population available at the level of individuals and households. “The richness of this data is something that no one has been able to unlock before anywhere in the world.

“You can now follow people over time, generations even. You can see whether people migrated. We can conclude a good many things about, for example, demographics and marriages.”

Fourie says he was surprised at the extent to which people in the colonial era underreported their tax returns. “We can calculate this because we have access to the estate inventories and the previous years’ tax returns. Suppose someone has 50 cattle, but when he dies, suddenly 100 cattle are recorded. People typically reported only about 50% of their assets. I would never have thought that tax evasion was so big at the time. It’s substantial.”

Using machines to connect the dots

Some of the challenges that the researchers have encountered thus far include correctly matching people and data over time.

Fourie gives the example of one of his own ancestors, the Huguenot refugee Louis Fourie, who was documented by the VOC for the first time in 1700 and the last time in 1750. “His data must be connected over time, but his name is spelled 13 different ways in the first 13 years it was recorded.”

Machine learning offers an efficient way to track Louis Fourie and the many other men like him, Fourie says. “You adjust the algorithm so that it picks up the different spellings of a particular name. Also, Louis Fourie has a son with the same name, so the algorithm must be taught to read this Louis’ data separately. And now, say the older Louis marries another woman, but in 1713 the younger Louis also marries someone else... The algorithm must be able to indicate that the data on a particular wedding certificate is this Louis’ data and not the other’s.”

The researchers map the various datasets brought into the project in such a way that the initial Louis Fourie is connected to his children, his children to their children, and the latter to theirs.

“Now, we have this household panel data spanning across generations. In this way, we can see Louis Fourie was rich, his children were not so rich, but their children were affluent again. You can thus compare people’s life cycles across generations. Globally, there has never before been such a wealth of detailed data for a project of this nature.”

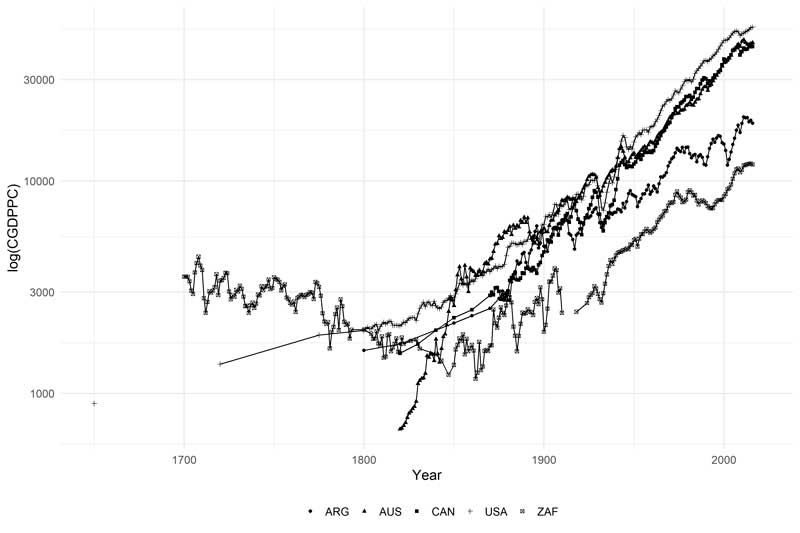

Comparison of real GDP per capita (2011 US$, logarithmic), Argentina, Australia, Canada, the USA, and South Africa, 1650–2016. Source: Maddison Project

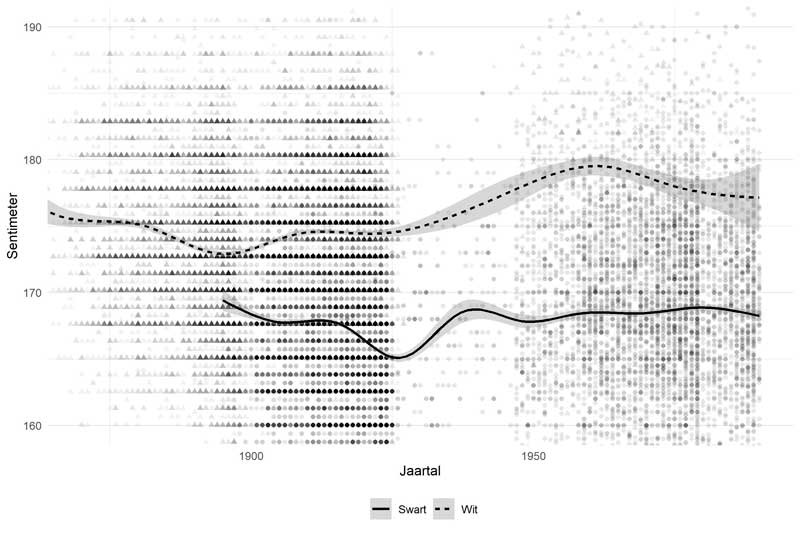

The height of black and white men, 1870−1990

Different sources to complete the story

Fourie juxtaposes LEAP’s research with that based on the typical kind of census that documents the existence of a particular individual every 10 years only. “Finding the same person in the data from the following census is difficult because there’s been 10 years of changes in the meantime. [...] With our datasets, you see evidence of the same person in each year of their life, and the same for their children. That means an enormous change. There is now an incredible amount of information.”

In addition to tax documents and family and slave registers, the LEAP researchers also have access to, among other things, estate inventories. The latter lists all the possessions someone had when they passed away. These inventories become important for several reasons, the research shows.

“The tax documents show a person’s agricultural assets, what they produced, and the number of slaves, cattle, and sheep they owned. A verified will presents a more detailed picture. If an estate inventory was drawn up, then most of it was auctioned off. The auction rolls give you prices for everything,” says Fourie.

“Using all these documents, you start uncovering networks. You can see who was at the auction of Louis Fourie’s estate after he passed away and who in the district attended it. You can find them, in turn, in the tax documents. This research shows you dynamic networks over time.”

The archives documenting life in the Cape under the VOC are very detailed. The reason for this is because the VOC was a company and not a colonial power in the traditional sense of the term. This means that the company systematically collected and preserved information for tax purposes, Fourie explains.

Conditions in the Cape have helped retain this wealth of data. “Cape Town has never had a war or experienced a major natural disaster. The VOC archives of the Cape have also been well preserved.

“The VOC didn’t manage other large settler colonies. The idea was not that the Cape should become a large colony, but that everyone here around Cape Town should have small farms. Then, the settler community expanded. This resulted in an enormous administrative system.

Having a census of that kind every year must have had tremendous costs for everyone involved. But the VOC needed this detailed work for the taxes they collected, so it was important for them to do it.”

“I recently co-wrote an article [with Frank Garmon of the Christopher Newport University, Virginia] that compares the tax records in America with the tax records here. We show that the Cape was much more prosperous than America at the beginning of the 19th century.”

And how does the data dating from the era of British rule over the Cape compare with that of the VOC?

“What we see is that when the British took over towards the end of the 18th century, the VOC was no longer the entity it was initially,” explains Fourie. “The British actually did a very good job of rebuilding the quality of the records and, for the first few decades, the British continued with the same system the VOC had used.”

Read more

Projects: The Cape of Good Hope Panel, Biography of an Uncharted People and Frontiers of Finance

Book: Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom

Journal article: “The settlers’ fortunes: Comparing tax censuses in the Cape Colony and early American republic”

Fourie’s inaugural lecture: South Africa’s Long Walk to Economic Freedom: A Personal Journey

Fourie’s doctoral dissertation: An inquiry into the nature, causes and distribution of wealth in the Cape Colony, 1652–1795

Twitter: @JohanFourieZA, @Leap_SU and @MatiesResearch