Digital advancements expand Africa’s economic history

Willem de Vries

Since the launch of the Laboratory of Economics of Africa’s Past (LEAP), its projects have contributed to widening the scope and awareness of the economic and social history of Africa. The research group at the heart of this laboratory have done so in a systematised and innovative way, using quantitative tools to uncover facts and trends that inform a larger narrative.

Prof Johan Fourie is the coordinator of LEAP and its programmes, hosted in the Department of Economics at Stellenbosch University (SU). He sees the group’s work as representative of the renewed global interest in economic history since the early 2000s.

The origin of LEAP dates back to 2009 when SU had the opportunity to submit a bid to host the World Economic History Congress, says Fourie. Stellenbosch ended up being chosen as location over Glasgow and Sydney.

This selection gave Fourie and the rest of the group of researchers at SU energy, partly because international colleagues could suddenly see that something was happening here, Fourie recalls. “I got my first PhD student in 2013. In 2015, we founded LEAP.”

The first LEAP project (on the economy and social history of the Cape at the time of the Dutch East India Company), ran from 2015 to 2019 under the leadership of Fourie and Dr Erik Green from the University of Lund in Sweden.

“This project started out with much less funding than is the case today. However, its potential was apparent, so we later received a grant from the Bank of Sweden’s Jubilee Fund Foundation – the largest amount awarded to a project of this nature in Sweden to date.”

Fourie finds it frustrating that quantitative historical research was not encouraged in South Africa until recently. “This means that you simply cannot answer certain questions about South Africa if you do not have access to the relevant techniques, nor have mastered them.”

Telling our own stories

For Fourie, economic history is “largely about telling a story”. People absorb facts more easily through narratives, he says – much more so than through statistics.

“The kind of story that LEAP writes through quantitative means offers a different picture of history. When we think of history, we think of our own stories and how we fit into the bigger story.

“The challenge for economic historians is that we typically work with averages and not outliers, which is what traditional historians and biographers tend to focus on. However, to tell these stories – those of the average person at a certain time – you still want to write as if it were the story of an individual. It’s an interesting challenge.”

The large amounts of data LEAP analyses and then uses to calculate average trends give different answers to those offered by traditional historiography. “It also answers different types of questions”, he points out.

“If you have a question about the average income of a person, you can’t really find out from newspaper articles, letters or the like. For that, you need other techniques. And this is where we make an important contribution. Also, the book I wrote is a way to capture these broader trends in the stories of individuals so that they can serve as an example of the rest.”

In this book, Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom, published in 2021 by Tafelberg, Fourie examines lessons from economic history that span 100 000 years of human history. He critically engages with the question of what contributes to and detracts from creating wealth.

In writing the book, Fourie prioritised bringing African perspectives from the continent itself, rather than from elsewhere, to the economic history of Africa. He sees LEAP as a part of what he describes in his book as “a renaissance in African economic history”.

Asking the right questions

Fourie is joined at LEAP by two other permanent staff members, Prof Dieter von Fintel and Dr Calumet Links. In addition to master’s and postdoctoral students, an extensive group of collaborators, co-authors, and two extraordinary professors from the universities of Utrecht and Arizona are also involved in LEAP’s research projects.

The group’s interdisciplinary work shows that a topic such as the economic history of South Africa in the colonial era has substantially more to it than can be claimed by research done in a single traditional subject area. Moreover, it shows that such topics can now be unlocked on a scale previously impossible.

Fourie emphasises the use of machine learning and other new techniques to analyse the large datasets that LEAP works with, and is increasingly factoring it into projects’ upcoming phases. “We experiment frequently with new methods. Some of them are more successful than others. But this is what research should be all about.

“Most people who pose the question about the reasons for poverty are rich,” Fourie says. “But the historical norm, one should remember, is that people have always been poor. For most of humanity’s existence, people lived just above subsistence levels. Infant mortality was extremely high.

It is only in the last three or four generations that life has become much better for most of us. ‘How did we get so remarkably rich?’ is the question economic history tries to answer.

Well, to create order, one needs to spend energy. So why is it that certain people or certain countries use the energy they generate productively to create surpluses that improve their lives? This is the question we must keep asking.

“We at LEAP want to contribute to an international conversation. We’ve got strong connections with some of the leading universities in the world. There is also a lot of overlap with other research units. The one that comes to mind immediately is Research on Socioeconomic Policy (ReSep), the development economics unit in the Department of Economics here at Stellenbosch University. They ask the same question about poverty that we do about wealth. We learn a lot from one another.”

For Fourie, the goal is to do research that makes us better understand the world, ourselves, time, and place. “These high-quality research projects focus on a very complex society. As researchers, we especially want to bring to light the parts of history that were not fully illuminated before.”

The preservation of complexity is of equal importance in Fourie’s research. LEAP’s approach is not necessarily only geared towards finding answers but also towards reaching insights that enable academics to ask better questions.

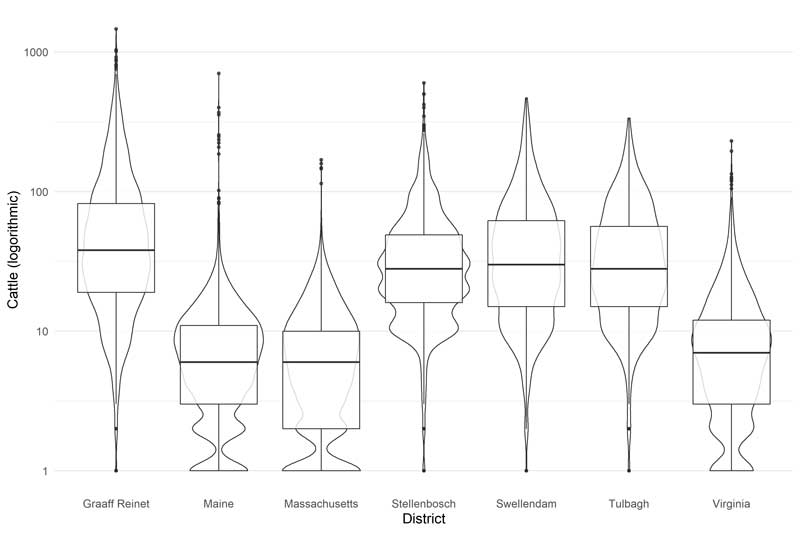

Comparison of cattle ownership by district, pooled years. Source: Various tax censuses

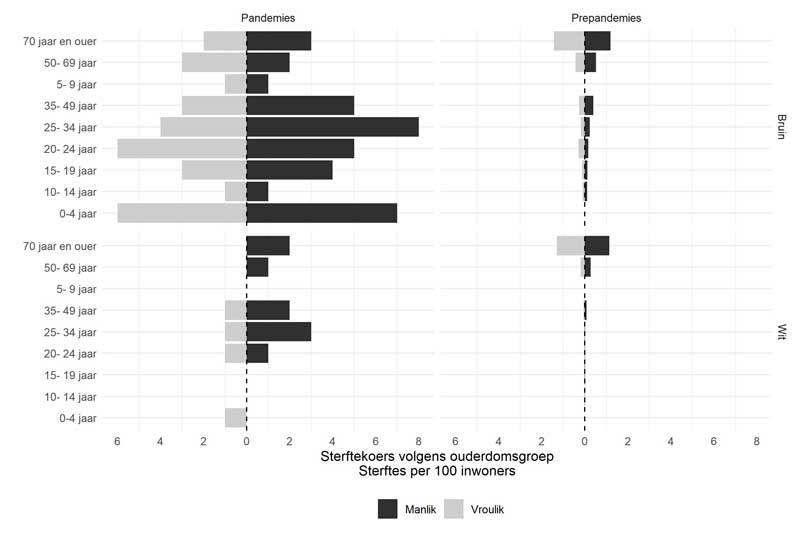

Deaths divided into race, age group, gender and pandemic era, Paarl (1915 -1920). Source: Litnet

Teaching machines to unlock history

For LEAP’s researchers, unlocking big data from the past requires the systematic analysis of various archives using techniques from the digital humanities. Academics working in this mode are expanding their existing research tools to include image recognition software, algorithms that help with text analysis, and programs that easily process large datasets.

The digital humanities hold enriching implications for the pace at which research can be conducted, and for the ways in which research can be presented and interpreted. As such, a part of LEAP’s work is to equip the historians of tomorrow with knowledge of the new techniques through which sources can be analysed.

Explaining LEAP’s work, Fourie says the physical source documents are first made available digitally, then transcribed. “One can do the transcription by hand. However, there are more and more machine learning techniques that can help you do that automatically.”

Fourie explains this using the example of death certificates, information recorded on a standardised form. “Suppose you have a million of these. Rewriting it by hand is going to take time. So now, you transcribe ten thousand by hand and then you tell the computer what this and that thing mean. Over time, it learns the meanings of the words. It still makes mistakes, but the mistakes, interestingly enough, are systematic. If you know what mistakes there are, you can easily fix them. There is more and more software available to help you do this. In the next five years, we will do something like this with really big datasets.”

Transcribing sets of data also means identifying gaps. What does a usable, wholesome dataset look like?

“It is important to emphasise that LEAP is not saying the study of history as it is currently done is something that should be done away with. What we are saying is that some of the questions about history simply cannot be answered using traditional methods,” he clarifies.

“If you want to know what people were thinking at a specific time, then you need written records. Did they do what they set out to do? Then you also have to look at what they bought more or less of. There are gaps in the data and, of course, one must also show sensitivity about data and aspects of a time that we may judge differently today. You don’t want to condone the relevant period, but you want to understand it.”

Since the start of 2022, author and historian Karen Jennings has been doing postdoctoral work at LEAP. Her historical novel An Island, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2021, was recently published in America. In The Guardian, the “small but powerful” book is described as a “fable about the turbulent history of an unnamed African country”.

Jennings now aims to turn her research at LEAP into a narrative about the emancipation of slaves in the Cape. For this, she is drawing on LEAP’s records and the enormous datasets contained therein. “If all goes to plan, the manuscript will be completed by next year,” Fourie says. “This kind of work brings statistics to life and makes it a part of larger conversations. I’m very excited about it.”

An overview of LEAP’s research projects

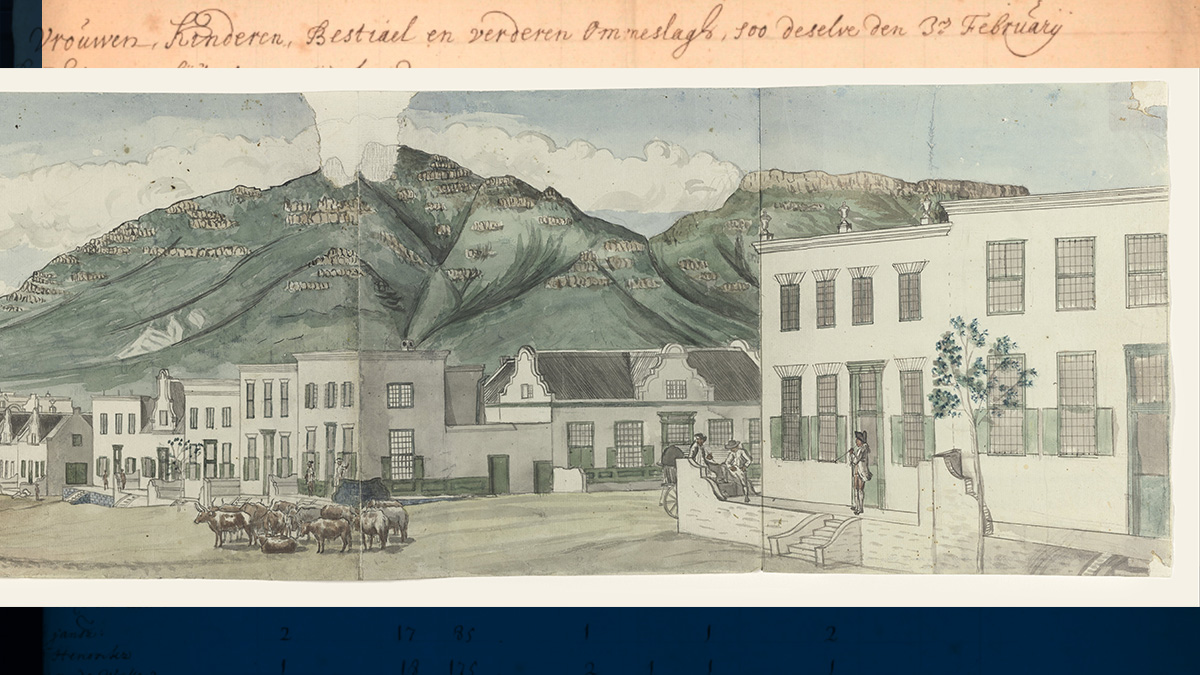

The Cape of Good Hope Panel is a series of annual tax censuses (‘opgaafrolle’) collected by the colonial authorities in the Cape Colony during the 17th to 19th centuries. The censuses contain information about not only the complete settler population – by the end of the period, a total of more than 50 000 individuals – but also about the indigenous, enslaved Khoesan population that lived and worked within the colonial economy. Researchers involved in the Panel project are using this data to investigate economic development, the evolution of living standards, inequality, social mobility, elite formation, slavery and labour coercion in the colony at this time.

The digital humanities project titled ‘Biography of an Uncharted People’ involves scrutinising administrative databases for information about South Africans, particularly black citizens, who were often excluded from censuses and reports, and underrepresented in other types of archival records such as personal collections of letters. Individual-level records are a treasure trove of information about the economic, social, demographic, health, labour, genealogical, and migration histories of the Cape Colony and South Africa at large. Even though digitised records are available online, they are largely inaccessible to most South Africans. The only systematised series of birth, marriage, and death records available at present represents only the white population. By making historical information easily accessible, the Biography of an Uncharted People project gives dignity to black, Coloured, and Indian South Africans, and enables them to bring to light the histories of families that were overlooked in the past. The project makes use of large, previously unexplored datasets, analysing the information systematically to contribute to debates in South African history.

The Frontiers of Finance is a research project that studies the financial and business history of the British Cape Colony. Funded partially by the South African National Research Foundation, the project examines the emergence of joint stock companies in the Cape Colony, and in Southern Africa more broadly, from 1862 onwards.