An activist for excellence

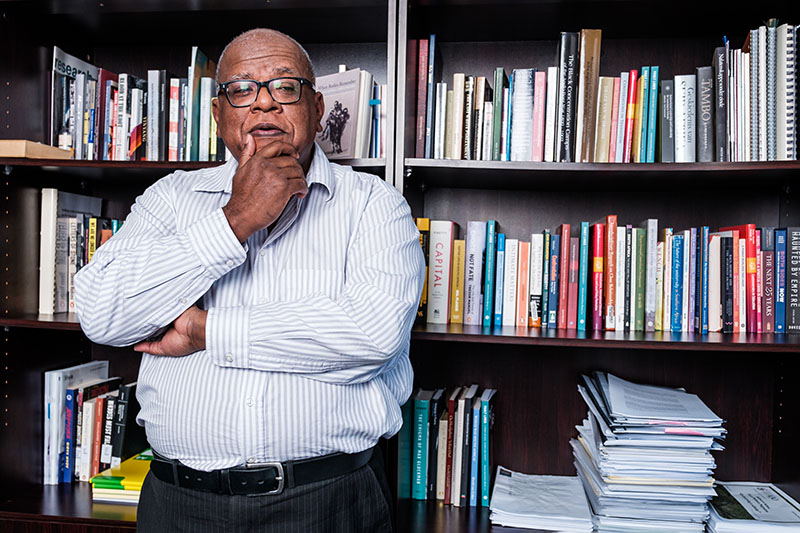

Few A1-rated academics can, among their outputs and citations, list that their tweets in support of Springbok rugby were quoted in newspapers. But such is the public following of Prof Jonathan Jansen, distinguished professor in education at Stellenbosch University (SU) and president of the Academy of Science of South Africa.

In 2022, the 65-year-old thought leader on South African education and the country at large received his second A-rating from the National Research Foundation. When he received his first, he was still rector and vice-chancellor of the University of the Free State (UFS), a position he held from 2009 to 2016, after which he joined SU in 2017.

Jansen has received honorary degrees from universities in Scotland, the USA and South Africa, the Education Africa Lifetime Award, and Stanford University’s inaugural Alumni Excellence Award. He is a fellow of the International Academy of Education, and in 2021 received the Human Sciences Research Council and Universities South Africa’s gold medal.

However, Jansen is proudest of his academic and popular books and articles, the young academics he has mentored, connecting with his Twitter and Facebook followers, and engaging readers through his weekly opinion piece in The Times and other newspapers over the past decade.

This motivating speaker reckons he has visited more local schools than most politicians.

His recent message to attendees of the International Conference on Chemistry Education was clear: “Teach with attitude, teach for meaning, and teach for change.”

An academic activist

As an activist for academic excellence and a better South Africa, Jansen takes his ‘civic duty’ as an academic seriously. His critique isn’t always well received, though, and therefore he has had to develop some of the thickest skin in South African academia.

Jansen describes himself as a comprehender rather than a stirrer – he wants to understand complex aspects of science and society.

But, to use one of his favourite phrases, “Here’s the thing …”

Despite being so visible and vocal, Jansen doesn’t want to be remembered. At all.

“I want people to remember those in whose lives I’ve made a difference. In the bigger scheme of things, I am irrelevant to this world.

“My late mother always switched to her childhood language of Afrikaans when she wanted to leave you with some beautiful wisdom. She would, for instance, say: ‘Dis alles net die genade’. It’s all through grace.”

Shaping futures

Jansen describes himself in fewer characters than is allowed in a tweet: “I am absolutely passionate about teaching, and passionate about making the world I live in better for others. That’s it.”

He has been doing exactly this since finishing his BSc studies at the University of the Western Cape and accepting his first teaching post in Vredenburg in the 1970s. The trend continued throughout his subsequent positions, such as dean of education at the University of Durban-Westville and at the University of Pretoria (UP).

It’s in his DNA to challenge others to grow and find their own personal and intellectual worth, and to support them in doing so. He has done this for his two children and hosts of younger academics.

These days, leading and teaching the first two cohorts of South Africa’s Future Professors Programme, based at SU, provides him great joy. Building on a concept that Jansen developed as the UFS rector, it prepares senior-lecturer-equivalent scholars to take up their positions among the professoriate.

“I get the thrill, the joy, of seeing senior lecturers in 26 public universities become associate professors and professors. What a feeling, what a rush that is!”

Intellectual puzzles

Jansen himself has been inspired and challenged by significant figures in his life. Among them are psychologist Prof Chabani Manganyi, a valued mentor during his time at UP.

“One day, he said: ‘You know JJ, your problem is you get angry before you think.’ Since then, I’ve been turning even the most grievous, upsetting problem into an intellectual puzzle.”

One of the results of this feat is Jansen’s award-winning book Knowledge in the Blood: Confronting Race and the Apartheid Past (2014), which won the British Academy for the Social Sciences and Humanities’ Nayef Al Rodhan Prize. The book considers how young, white, Afrikaans-speaking youth have come to embrace a past that they were never a part of.

Jansen still rates this his “most impactful” book.

“It did something that nobody expected: Instead of just talking about how white, Afrikaans youth acquire knowledge about our past, it was a profoundly intimate story about how they transformed me, the first black dean of education at Tukkies.

“I don’t think people could have guessed that it would be so personal,” says Jansen, who grew up on the Cape Flats.

“No one had yet written so intimately, so close-up about the intergenerational mechanisms involved in the transfer of knowledge in post-traumatic societies – not at that level of detail. That’s even true in the case of the thousands of books on the Holocaust.”

The joy, and value, of writing

Jansen tries to write at least one academic and one popular book per year, often in conjunction with colleagues or former students. In 2022, he produced four.

“The day I stop writing is the day I stop breathing. The day I stop thinking is the day I stop existing,” says Jansen, for whom six hours of writing is pure relaxation, as is playing jazz on the piano.

“Several of my books are aimed at the broader communities in which I live and work. It’s how I translate my research works into practical and accessible ‘science communication’ as a part of my public service commitments.”

“Coming up with new problems to solve through thinking and writing doesn’t feel like work. I love the life of the mind.”

Among Jansen’s many publications are As by Fire: The End of the South African University (2017), which won an SA Literary Award. Who Gets in and Why? (2019) documented the first empirical study to link the micro-politics of school desegregation to the macro-politics of social transition, while The Decolonization of Knowledge (2022) examined the uptake of curriculum in 10 public universities.

The politics of knowledge

Jansen’s interest in curriculum change, institutional analysis, political science and the politics of knowledge was shaped in the 1980s, when he was a young high-school biology teacher looking for alternatives to the apartheid curriculum. His ideas on these topics were honed through postgraduate studies and by mentors such as Prof George Posner from Cornell University and Prof Hans Weiler from Stanford University in the US.

Jansen says research, science and the official knowledge (curriculum) built up around it are never really neutral, value-free or without baggage. Power, politics, the time frame and context all come into play.

“When deciding what to teach, for instance, you must be selective because there is so much knowledge to choose from. The moment you make a selection, you include some things and exclude others. And that is the politics of knowledge, pure and simple.”

In 1991, Jansen received his PhD on the politics of knowledge from Stanford University and published his first major work on the concept, titled Knowledge and Power: Critical Perspectives Across the Disciplines. The book critically analysed the concept within fields such as nursing, anthropology, urban planning and dentistry.

The topic of so-called ‘imperial durabilities’ in the medical sciences is one Jansen has returned to recently. He is considering how it plays out in the fields of human anatomy and genetics in South Africa.

“You cannot understand the power of medicine without looking at history. It allows you to understand the lingering effects of troubled knowledge.”

Prof Jonathan Jansen

Photo by Stefan Els

Written by Engela Duvenage