Music archives promote sociocultural understanding

Prof Stephanus Muller

Prof Stephanus Muller is the director of the Africa Open Institute for Music, Research and Innovation (AOI) at Stellenbosch University (SU). Research done by this acclaimed writer and academic has led to the establishment of the Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS) at SU. Muller spoke to Willem de Vries about his research, the founding of DOMUS, the role of music archives, digital humanities and what lies beyond.

Muller’s work shows that conducting research into compositions is to realise the inherently trans- and interdisciplinary nature of music, which is in itself a varied archive. DOMUS is proving to an ever-broadening extent that the study of music is a rich source for the interpretation of both itself and other genres and disciplines, thereby contributing to various academic discourses and societal concerns.

You are the much-lauded author of Nagmusiek (2014, ‘Night Music’), for which purpose you catalogued the music manuscripts of the South African composer Arnold van Wyk. The collection marks the beginning of DOMUS. How did this documentation centre come to be?

The idea of DOMUS started, as you correctly state, with my work on the Arnold van Wyk Collection, held in the Africana section of the SU Library. This work started in 2002, and was partly funded by the late Huberte Rupert (the influential philanthropist with a special interest in arts and culture). As I worked through the materials held in the Africana section of the library, I became aware that a much larger portion of Van Wyk’s materials was held at the Nasionale Afrikaanse Letterkundige Museum en Navorsingsentrum in Bloemfontein. This collection was eventually transferred to the University on permanent loan. I remember with great appreciation the support and wisdom of the then head of Africana, Hanna Botha, whose gentle diplomacy guided the progress we made in constituting Van Wyk’s archive at SU. When I was appointed as a lecturer in SU’s Department of Music in 2005, I formalised DOMUS as an archive-based scholarly project that is intimately concerned with improving research and preserving South Africa’s music heritage.

Nagmusiek by Stephanus Muller was published in three volumes with hard covers and a slip case by Fourthwall Books. Muller was awarded various awards for the work, such as the Eugène Marais Prize, the kykNET-Rapport Prize (non-fiction) and Jan Rabie Rapport Prize for debut fiction, as well as the University of Johannesburg Debut Prize for Creative Writing in Afrikaans.

Since DOMUS was started in 2005, it has grown exponentially, accumulating a varied range of music collections. Are there additions to DOMUS that you are particularly glad are housed there, and why?

Every single collection that arrived at SU during the time I headed up DOMUS, and now that I no longer do so, means something deeply personal to me: a victory against forgetting, a defiant affirmation of the importance of art in the university, and a stand taken in the cultural entropy inimical to the fragile, the vulnerable, the transient, the beautiful, the marginal and the joy of the non-utilitarian. Having said that, there are collections that are symbolically of major importance to SU in terms of transforming its image from that of a custodian of white supremacist culture to an institution that values the cultures of all South Africans. These collections include the Eoan Group Archive, the Taliep Petersen Archive and the Surendran Reddy Archive, which will arrive in 2023. By taking in these archives and looking after them, we are saying that SU has changed, that it no longer exclusively values the musical culture that used to be called ‘European’, and that we are investing resources into this form of transformation.

The AOI and SU’s Department of Music play an important role in procuring collections. What is the role of DOMUS today in terms of collating special collections at a university level? How does DOMUS tie in with the larger landscape of music archives in South Africa and elsewhere?

I think it is reasonable to say that DOMUS is the largest university-based music archive in the country, and possibly on the continent. As continually proven by research (most recently Dr Paula Fourie’s magnificent book on Taliep Petersen), it also presents a model for scholarly involvement and engagement with archives that, if allowed to flourish by institutional structures, will change the scholarly and archival landscapes of our and other disciplines beyond recognition in the next few decades.

What are current research focuses and trends pertaining to the DOMUS collections? How involved do you remain with DOMUS?

When DOMUS became a Special Collections Section of the SU Library in 2016, a decade after its founding, I relinquished control over acquisitions, processing, strategy and planning. It was very difficult for me, as DOMUS was a scholarly project in which I had invested 10 years of my academic career. Today, however, I am still involved in DOMUS via the AOI, which continues to pursue research that leads to new DOMUS acquisitions, and develop research foci in the materials already at SU. For example, the Hidden Years Music Archive (HYMA), acquired and funded for many years by Prof Lizabé Lambrechts, is the subject of her ongoing research into the Free Peoples’ Concerts. Prof Willemien Froneman and I are working on materials associated with the South African music avant-garde, and Dr Hilde Roos will be publishing, along with two colleagues, (contained in the Eoan Group Archive) in 2023.

Is it important that the DOMUS collections be digitised in their entirety? What are the criteria whereby artefacts should be made available digitally?

Digitalising all DOMUS collections would be impossible with the resource constraints that pertain to this kind of work here but also elsewhere in the world in better-resourced contexts. Two factors are important: Preservation of materials and directed creation of access to scholarship. With regard to the former, it stands to reason that materials that are constantly deteriorating (like sound recordings in old formats, or compromised photo negatives) should be digitised as a matter of priority. As regards the latter, scholarly interest is a good way to both determine priorities and obtain funding from research or other funding streams to assist in archival functions. This requires teamwork and collaboration between as many institutional and extra-institutional stakeholders as possible. We have to look upon this work as the shared interest of South Africans, not as the special interest of scholars, librarians or a single university isolated from the broader cultural ecosystem in which we exist.

Internationally, across tertiary institutions, the digital humanities have come to the fore, bringing with it new ways of unlocking and cross-referencing collection items. What influence do the digital humanities have on the archival work and practices at DOMUS?

DOMUS digitises collections, which are then housed by the SU Library and Information Service. But the AOI is experimenting with differently curated forms of digital archival work in advance of the digital humanities agenda through our online enriched-media archive and provocative e-journal herri, and through other projects like the Genadendal Music Archive .

The work done at DOMUS reveals the inherently inter- and transdisciplinary character of music, as well as changes in academia and society’s ways of thinking through and about music. What have been the major trends in how music is researched since DOMUS was started, and how do they reflect the ways in which special collections form part of a larger discussion about and in society?

That is a very perceptive comment. I think the best current example of this kind of work from within our institute is the research of Prof Willemien Froneman. Her work, which started out as a scholarly investigation of boeremusiek (South African folk music), led to the acquisition of a large archive of this music type, which is now part of the DOMUS collections. Froneman’s work is archivally based – I think, for example, of her writings on Jo Fourie – but music research has become for her a pen with which to write in a radical, post-disciplinary way about whiteness and affect. Her monograph on the subject will appear in 2023 and represents, in my estimation, a brilliant refining of and advance on thinking about race as constituted in and through aesthetics and affect, so influentially articulated by the author JM Coetzee in the 1980s. So, in light of the recent Khampepe report on racism at SU, I can think of no more relevant research, suggestive not only of an aesthetic or social analysis but of a transformation agenda.

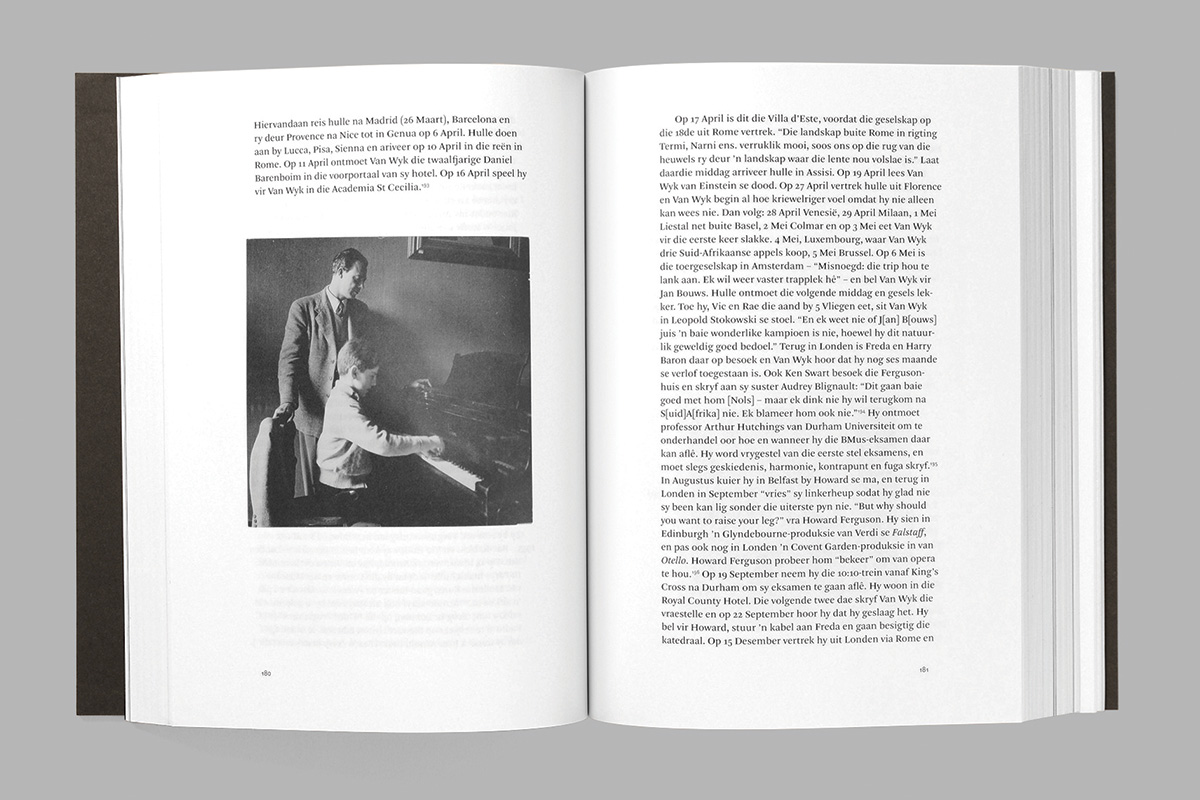

Nagmusiek has been described as "both a scholarly study of the Afrikaans composer Arnold van Wyk and a work of fiction in which the author/biographer — who is and is not Stephanus Muller — hijacks his own literary undertaking". The publisher announced the work in 2014 as "an extraordinary meditation on the art of biography, on South African classical music under the apartheid regime, and on the complicated relationship between life and fiction."

What are currently some of the oldest works included and accessible in the DOMUS archive, be they physical or digital?

The oldest archives in the Music Special Collections precede the creation of DOMUS in 2005. These include the Albert Coates Collection, which can actually be viewed on SUNDigital. Much older still are items in the collection of Commander Michael Scott, which includes extremely valuable music scores, letters, monographs and facsimiles.

What have been constraints and what have been the most positive developments at DOMUS since it was founded?

Funding and resources are always constraints. This impacts not only on the processing of materials but also on more basic things like storage facilities with ideal conditions for the preservation of different media, and conditions conducive for the kinds of creative intellectual interactions that I regard as the life force of the University. The most positive development is the fact that the archival holdings of DOMUS continue to expand, not only in quantity but also in its reflection of our region and country’s richly diverse landscape of musical culture.

Looking to the future, what are the plans for DOMUS? Are there any forthcoming projects or publications that specifically illustrate something of DOMUS’ research philosophy or approach?

The long-term planning for DOMUS certainly includes establishing a proper archive. With this I mean not only facilities that will preserve our heritage in a responsible manner but also support the kinds of human interactions that constitute a culture of learning, scholarship and refined aesthetic and academic sensibility. I have dreamt of this for many years: At the centre of the dream there is always a beautiful reading room in which I sit, surrounded by books and manuscripts, embracing the silence of shared immersion in things other than the tasks and burdens of the everyday. The AOI is a decolonial initiative, and its approach to DOMUS must be understood as such. For us, this means that we want to do better and more interesting work, think things that cannot be thought elsewhere, and discover what we can still only intuit. In 2023, scholars associated with the institute will publish three monographs. The first is on the tragic consequences of exile for one of the most internationally celebrated South African musicians of the twentieth century, who happened to be a coloured, gay man who was never able to fulfil his potential in South Africa. The second focuses on the reception of opera in the Western Cape, and the remarkable story of how opera became a laboratory for working out the ideas of the ‘New South Africa’ of the 1990s. The last monograph will investigate the pleasures and desires of whiteness, performed and imagined in boeremusiek through modalities of the subjunctive. There will also be a new, eighth edition of herri, guest-edited by Vulani Mthembu, on artificial intelligence in Africa. Find a philosophy or approach in those four things (there are many more!), and regard that as where we are heading.

An excerpt of pianist Daniel-Ben Pienaar performing Arnold van Wyk's work Nagmusiek. Read more here.

Useful links

Africa Open Institute for Music, Research and Innovation (AOI)

Twitter: @MatiesResearch