Forensic facial imaging laboratory promotes interdisciplinarity

Willem de Vries

Installation view of ID/Inventory (1999) and The Studio Familiar: X0198/1669 (2014) by Dr Kathryn Smith, from the exhibition Between Subject and Object: human remains at the interface of art and science | Photo by Dr Kathryn Smith

Stellenbosch University (SU) is the first tertiary institution in Africa to offer research and casework expertise in forensic facial imaging, a critical tool in human identification.

VIZ.lab is an imaging laboratory based in SU’s Department of Visual Arts. The laboratory was launched in 2021 by the Chair of Visual Arts, Dr Kathryn Smith — an interdisciplinary visual artist and curator — and Pearl Mamathuba, a forensic artist and PhD candidate at SU, joining VIZ.Lab as a full-time postgraduate researcher. As the only two academically trained forensic facial imaging specialists on the continent, the pair have a shared interest in working towards reinstating personhood through the lens of forensic art.

The imaging laboratory draws on both local and international expertise in its research projects that lie at the interface of art and science. Here, knowledge of facial anatomy, biological anthropology, forensic pathology, and cognitive psychology is blended with cutting-edge technology to perform craniofacial analysis, reconstruction, and depiction for both forensic and archaeological applications.

Dr Kathryn Smith and her VIZ.lab colleague, Pearl Mamathuba, with their collaborative work Fugitive | Photo by Phillip du Plessis

According to Smith, other universities offer short introductions to this field as a part of forensic anthropology or medical illustration modules. Some have special units that offer research support, such as Face Lab at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU), with which Smith has a formal affiliation as visiting research fellow.

When Mamathuba first contacted Smith about furthering her work academically, she was an employee of the South African Police Service (SAPS), with more than six years of experience in facial compositing.

In SAPS, she was working in the Facial Identification Unit, which is part of the Criminal Record Centre, where forensic officers conduct interviews and do facial composites of suspects. SAPS is structured in such a way, however, that the post-mortem work happens in the Victim Identification Centre, which falls under the Forensic Division.

Smith helped Mamathuba develop a proposal for doctoral research at SU, for which she has received a full scholarship. Her PhD focuses on the impact of visual style in the presentation and reception of forensic facial depictions, and on whether updating depictions using more contemporary methods (such as digital compositing instead of a clay sculpture) has an impact on the success of such images or, indeed, what factors do.

Unfolding interdisciplinarity

Smith has introduced a workshop titled ‘Introduction to Forensic Art and Illustration’ into the scientific illustration module of SU’s degree course Honours in Visual Arts (Illustration). “After starting out as a single-day workshop hosted during COVID-19 in 2021, it has been granted two weeks on the academic calendar from 2023 onwards,” she explains.

Smith also teaches courses at other universities in the Western Cape. At the University of Cape Town, she gives guest lectures as part of two separate postgraduate programmes: biomedical forensic science, where she teaches in the forensic anthropology module, and an interdisciplinary critical health humanities in Africa module, where she lectures on socio-cultural and forensic representations of death and the corpse. At the University of the Western Cape (UWC), in the Craniofacial Biology Unit (a part of the Faculty of Dentistry), she teaches an introduction to forensic craniofacial analysis, reconstruction, and depiction to postgraduate students in forensic odontology. She is also involved in a postgraduate course in forensic history in UWC’s Department of History.

In Smith’s experience, the Department of Visual Arts at SU is an apt home for her research into forensic art.

“SU has always been incredibly supportive of my interest in this field, particularly previous Chair of Visual Arts Prof Keith Dietrich and Prof Hennie Kotzé, in his then role as dean of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. They were the first to see the possibilities and supported my applications for study leave back in 2012. That said, when I started at the University of Dundee, SU wasn’t nearly as ready for the conversation about interdisciplinarity or art-science interactions as it is now.

“Subsequent faculty deans and research chairs have continued to support my efforts as I try to connect with other fields and programmes and contextualise the forensic in the broader art-science collaboration, or ‘STEAM’ [science, technology, engineering, the arts, and mathematics], field. This helps people familiar with STEAM concepts understand the less-familiar world of forensic art.

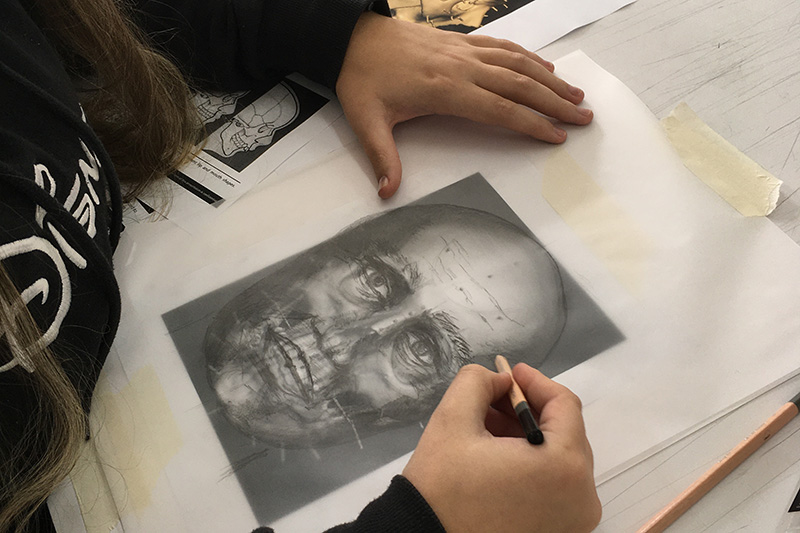

One of the SU honours students at work during a facial reconstruction workshop in 2021 | Photo by Dr Kathryn Smith

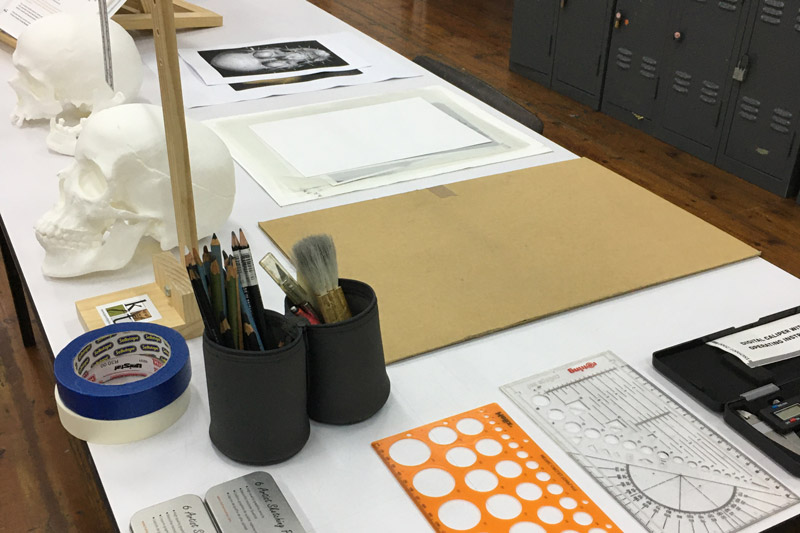

Tools and setup for the facial reconstruction workshops that form part of SU’s Honours in Illustration course | Photo by Dr Kathryn Smith

Practical hurdles to innovation

For Smith, being Chair of Visual Arts at SU “is a massively complex role”.

“I am currently focused on addressing our urgent staffing needs and appealing for a basic operational and capital budget to upgrade ageing infrastructure. The role allows for some strategic vision, but the day-to-day realities are very much about human resources issues and about building management systems.

“I am also trying to re-establish a world-class exhibitions programme for GUS, the University’s gallery, which our department is responsible for managing. It was transferred to us from the SU Museum in 2014, but given the post-#feesmustfall reality of institutional finances and commercialisation efforts, we have not had an operational budget or full-time curator for GUS since 2018, which is extremely challenging. I am applying every curatorial, ‘artist-run-space’ and project-management-with-zero-budget strategy I have gathered over 30 years!”

Smith also teaches fine art, integrated art and design, and drawing modules on first- to third-year level and supervises fourth-year theory of art and design, as well as studio practice. In addition, she teaches a part of the Honours (Illustration) programme and supervises postgraduate students in visual arts, visual studies, and clinical anatomy.

Moreover, she serves on the institutional committee for creative research outputs, advising on, coordinating, and reviewing submissions in the categories of art and design.

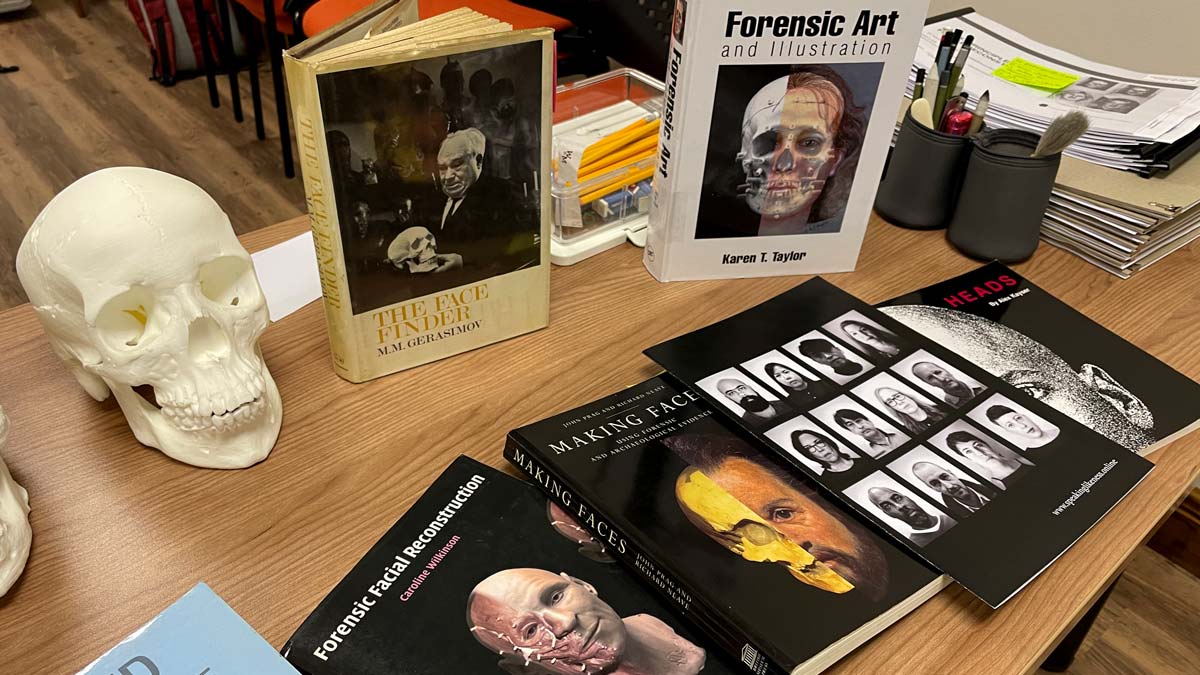

A collection of reference resources on display at a workshop held in 2022 at the University of the Western Cape for PGDip students in forensic odontology | Photo by Dr Kathryn Smith

Art as foundation across disciplines

Art is an inherently interdisciplinary activity, says Smith. “Research — whether visual, textual or empirical — underpins everything we do. That old saying about genius being ‘1% inspiration and 99% perspiration’ is true: The technical skills of most artistic methods can be learned. Sure, some people will have a more innate facility for drawing or whatever, but basic technique can be taught.”

Currently, Smith is working to grow VIZ.Lab’s ability to host postgraduate researchers working with visual cultures of science, object-orientated ontologies, and digital imaging. She also hopes to welcome students pursuing research in fields other than forensic art, including anatomy and related sciences, with a forensic identification application.

With a background in art and critical visual studies, one can move anywhere, Smith believes. “I think it’s really interesting that, over the last two years, requests to transfer to the visual arts programme, or do visual arts modules, by students currently registered for everything from agrisciences to engineering, have increased notably. It would be great to be able to accommodate these interdisciplinary interests and foster a real culture of curiosity and enmeshing of diverse skills.”

Thus far, Smith has co-supervised a postgraduate researcher doing an MSc on edentulous mouth morphology (that is, how tooth loss affects mouth shape), and is currently working closely with another MSc project mapping facial muscle volume. The latter is geared towards building a database of virtual facial muscles relevant to a local population. (The current lack of local research makes it difficult to know whether the data produced in other contexts for application in facial reconstruction work is, in fact, relevant to local populations, Smith explains.)

There is also a prospective doctoral student who is developing a proposal for a joint study with PXL-MAD (Hasselt, Belgium) in algorithmic design and the post-human. “Her background is jewellery design, so this gives you an idea of the transferability of core skills in digital 3D modelling, for example,” says Smith.

Forensic aesthetics: A modern approach in visual arts

Forensic art supports investigative intelligence in that it aids in the identification of both living people (suspects or persons of interest in active investigations) and that of the deceased. It is used in cases where conventional methods — using fingerprints, dental records, and/or DNA — have either failed or the necessary evidence is unavailable. In essence, it is art that supports a legal enquiry, she says.

“The word ‘forensic’ has become shorthand in everyday language for ‘detailed’ or ‘a close look’,” Smith remarks. “It immediately conjures those CSI-style animations of a bullet travelling through a body, as a metaphor for the forensic investigator’s penetrating gaze, looking beyond the surface, into the interior of a body or object. So, I also think of a ‘forensic gaze’ as one that is about touch as much as it is about sight.”

The ‘forensic turn’ in visual art can today be understood as a distinctly modern approach. Pivotal to its advent, Smith recalls, was a late-nineties exhibition in Los Angeles called ‘Scene of the Crime’, which was curated by Ralph Rugoff.

“He used the term ‘forensic aesthetics’ in the context of conceptual or performance artworks, where the work itself is an event. And what is then left of it is essentially a trace, or an artefact of the original event. As a viewer, you need to reconstruct the context that left this trace. Examples of such work include that of the artist Ana Mendieta, who created body silhouettes in the landscape, or Chris Burden, who did a performance during which he got shot in the arm.

“A key idea in forensic science is [Dr Edmund] Locard’s exchange principle, which says that ‘for every contact, there’s a trace’. Rugoff used it in reference to the forensic aesthetic, as a way to talk about particular kinds of artistic practice in which process-driven or site-specific actions may be reconstituted or understood via their traces.”

To assume a forensic approach in visual art, in Smith’s view, is to subject a scenario to a particular type of critical scrutiny, in the hope that new information can be produced. “Some art that operates in this space consciously adopts visual tropes that place it within what we now recognise as a ‘forensic aesthetic’. Examples include a close consideration of spills or stains, the presence of ultraviolet light, a particularly ‘cold’ or objective gaze, and the compulsion to reconstruct events via archival records or other textual or visual traces.

Breaking down silos

Forensic art is under-theorised from a social, cultural, and systems

perspective, something Smith tried to address in her doctoral research.

In many ways, she says, it is frustrating that forensic art is not

recognised by various professional groups internationally “but at the

same time, lack of regulation also has its advantages”.

Smith has immersed herself in art and science, integrating the two as a matter of course, given the interdisciplinary nature of art. But how does she see interdisciplinarity play out at the level of universities?

“It needs to have formal acknowledgement and support through funding, physical space to accommodate experimental work and cross-disciplinary conversations, and a recognition of those who lead in this space. I would love to have my current role better defined so that interdisciplinary innovation may be more fully recognised as a strategic objective.”

Even today, Smith says, universities are still structured as sets of disciplinary silos and covered in institutional red tape that frustrates collaborators.

“The clue is in the names we give — we call things ‘divisions’ and ‘departments’. ‘Schools’ and ‘centres’ offer an alternative, but they are often not fully integrated into the life of the institution. Collaboration within a faculty is somewhat easier than cross-faculty work, but cross-faculty and even inter-institutional collaboration is what we should be striving for.”

Smith says the reality in higher education is that there is increasing competition for ever-dwindling resources.

“So how do we square the affordances of collaboration with the vagaries of competition? Collaboration needs to be a generous and open conversation and can happen formally or informally. Currently, I have formal postgraduate supervision collaborations with the Division of Clinical Anatomy at SU, research collaborations with colleagues at UCT, and was involved in Prof Johan Fourie’s Biography of an Uncharted People project, which is an incredible synergy between economics and history via digital humanities.

“I am working on establishing research and service collaborations with SU’s Division of Forensic Medicine, and I am exploring interests in art-science interactions across the institution, with the help of a Finlo [Fund for Innovation and Research into Learning and Teaching] grant, for a project called ‘Fostering the Third Culture: A feasibility study to assess the viability of introducing a collaborative art/science learning and teaching focus at SU’. I hope this will inform the establishment of a taught postgraduate course in interdisciplinary art-science collaborations to solve specific social, environmental, and cultural challenges.”

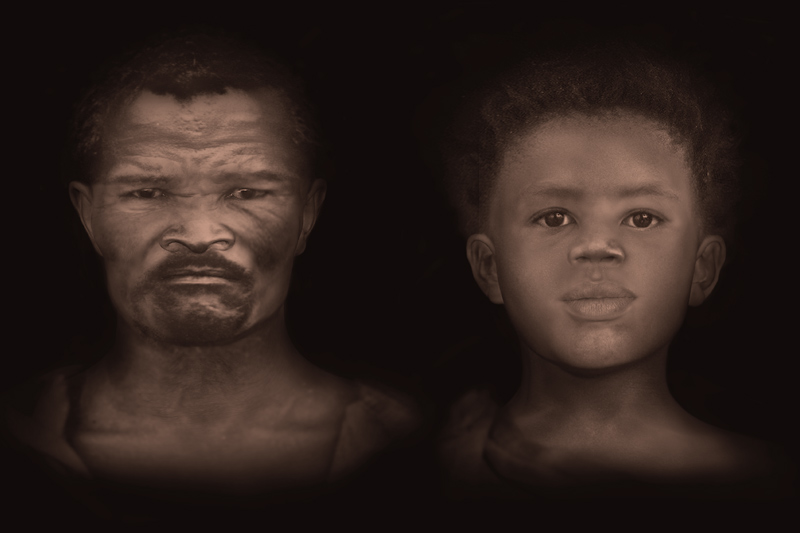

A facial reconstruction of two of the Sutherland Nine, a man named ‘Voetjie’ and a child named ‘Saa’. DNA analyses later helped to ‘reintroduce’ them to their San and Khoe descendants in Sutherland, long after their skeletal remains were donated to the University of Cape Town’s medical school. | Images courtesy of Face Lab, UCT, and the National Geographic Society

Dr Kathryn Smith and members of the descendent community viewing the facial reconstructions as part of the Sutherland Reburial Project in 2019 | Photo by Je'nine May, UCT

Investigating SA’s past through forensic art

Smith has participated in many projects over the years, notably as a co-curator of one commissioned by the Nelson Mandela Foundation for an exhibition called ‘Poisoned Pasts’, which looks at the legacies of the chemical and biological warfare programme in the country.

“It’s very much a social history exhibition, but it also asks questions around the dual uses of science — science for good or for bad,” Smith says. “The exhibition puts the viewer in the role of an investigator and you move through this largely unresolved and very complex and disturbing set of events, piecing together what is known and unknown.”

The exhibition opened in 2016 at the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and travelled to several venues. It is currently at the Ditsong National Museum of Cultural History in Pretoria.

Smith is working with Prof Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela to try to get the exhibition to Stellenbosch. Gobodo-Madikizela holds the South African National Research Chair in Violent Histories and Transgenerational Trauma at SU and was a member of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee.

New directions

“The most exciting recent development, however, is my connection with the new SARChI SciComm chair, Prof Mehita Iqani. We are actively exploring how visual arts can contribute to her agenda of ‘science communication for social justice’, which is at the core of my forensic and heritage work but gains broader scope in her vision. It’s telling that two of her postdoctoral students are both visual artists, now situated in a science communication environment — in journalism.”

Smith works in what she calls “the forensic humanitarian action space”. She and Mamathuba do forensic identification “while being very conscious of the kind of social biases that are built into the structural inequalities that make some bodies appear to matter more or less than others”.

Smith is also enthusiastic about developing a short course that will expose interested parties to the principles and techniques of forensic facial imaging, informed by the latest academic research and international best practice. It would not offer a formal qualification but could contribute to continuous professional development or add to existing skill sets in sculpture, drawing, and anatomy that are transferable to other industries, including animation.

The research initiatives reported on above are geared towards addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals numbers 9 and 16 and goal numbers 2 and 11 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.