Real-world research to curb South Africa’s scourge of cardio-metabolic disease

Ufrieda Ho

The burden of heart disease in South Africa is a ticking time bomb. Scientists know that it’s exacerbated by HIV and stress, but understanding exactly how and why is imperative to pushing back the clock. Researchers are looking at the deep local context as a critical key to unlocking solutions.

An intentional first step taken by the Centre for Cardio-metabolic Research in Africa (CARMA), established in 2020 in Stellenbosch University’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, has been the reframing of its research activities to be locally focused and appropriate.

Prof Faadiel Essop, the director of CARMA, says building more bridges between the research done at the centre and that done in a broad range of disciplines is necessary to modernise research in a way that makes it relevant to a wider audience.

CARMA’s collective research focus | Image courtesy of CARMA

True collaboration for greater public impact

“Research can be very focused on the individual — be it for personal achievement or personal promotion — and as a result, we researchers and scientists tend to duplicate our work, which is wasteful. We work in silos, and there are very few interdisciplinary links.

“CARMA wants to change this and also address the fact that we have very limited studies conducted in a developing-world context, which keeps a colonial legacy entrenched in our research approach.”

At CARMA, Essop says, they hope to go beyond superficial partnerships to thereby establish a robust platform for collaboration and knowledge sharing both within the University and among academics from across the country and continent. The centre’s aim is to build stronger, more enduring research capacity in Africa, as research emanating from here can attract new funding and grant opportunities. The latter widen the possible scope and output of research efforts and can ultimately inform more strategic, effective public health policies and life-saving interventions.

“The big-picture aim is to strive towards the eradication of the cardio-metabolic disease burden in Africa. Projections are that cardiovascular and related metabolic diseases, such as diabetes and obesity, will substantially increase on the continent.”

These diseases have become some of the trappings of modern living, which is marked by sustained high stress levels.

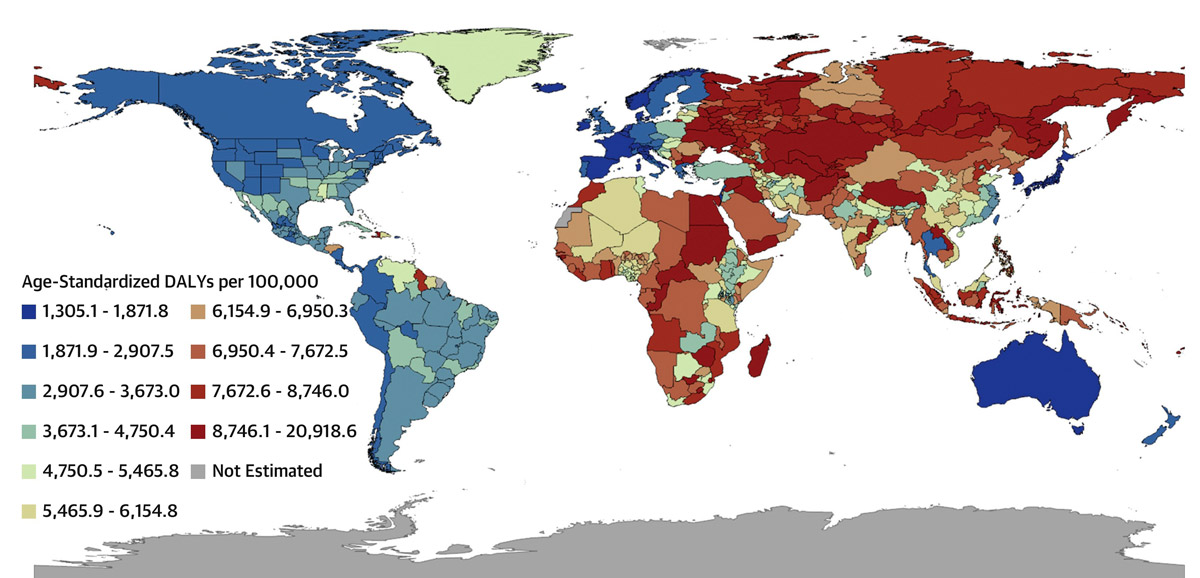

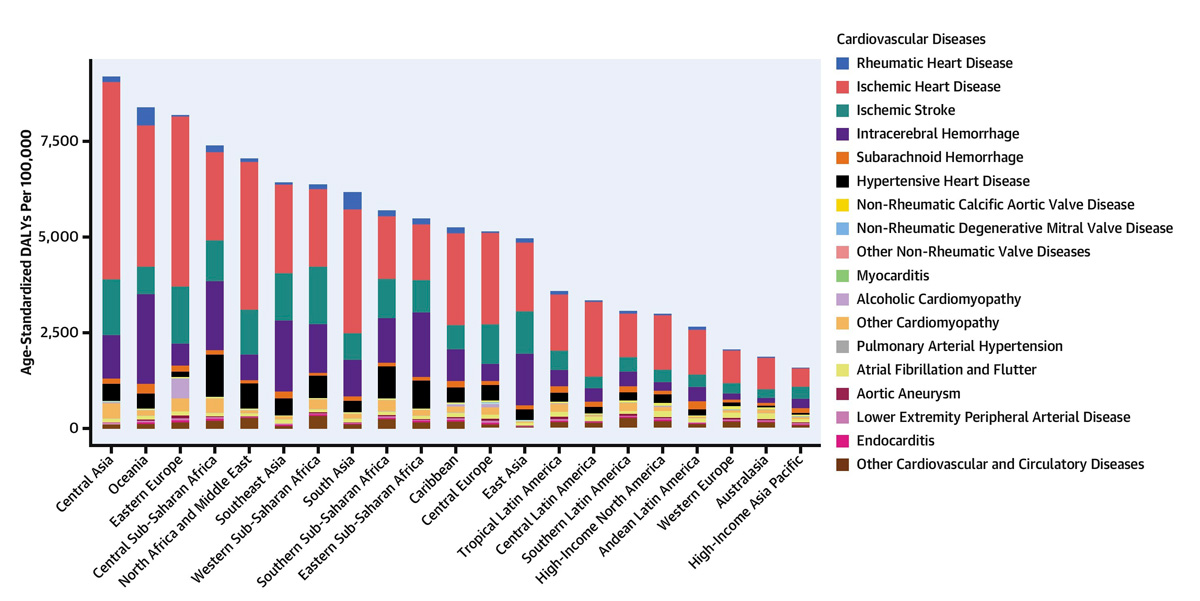

Cardiovascular diseases have collectively remained the leading causes of death worldwide and substantially contribute to loss of health and excess health system costs. Read more about it here.

Specific cardiovascular diseases by region. Read more about it here.

Stressful living: a slow crawl to disease

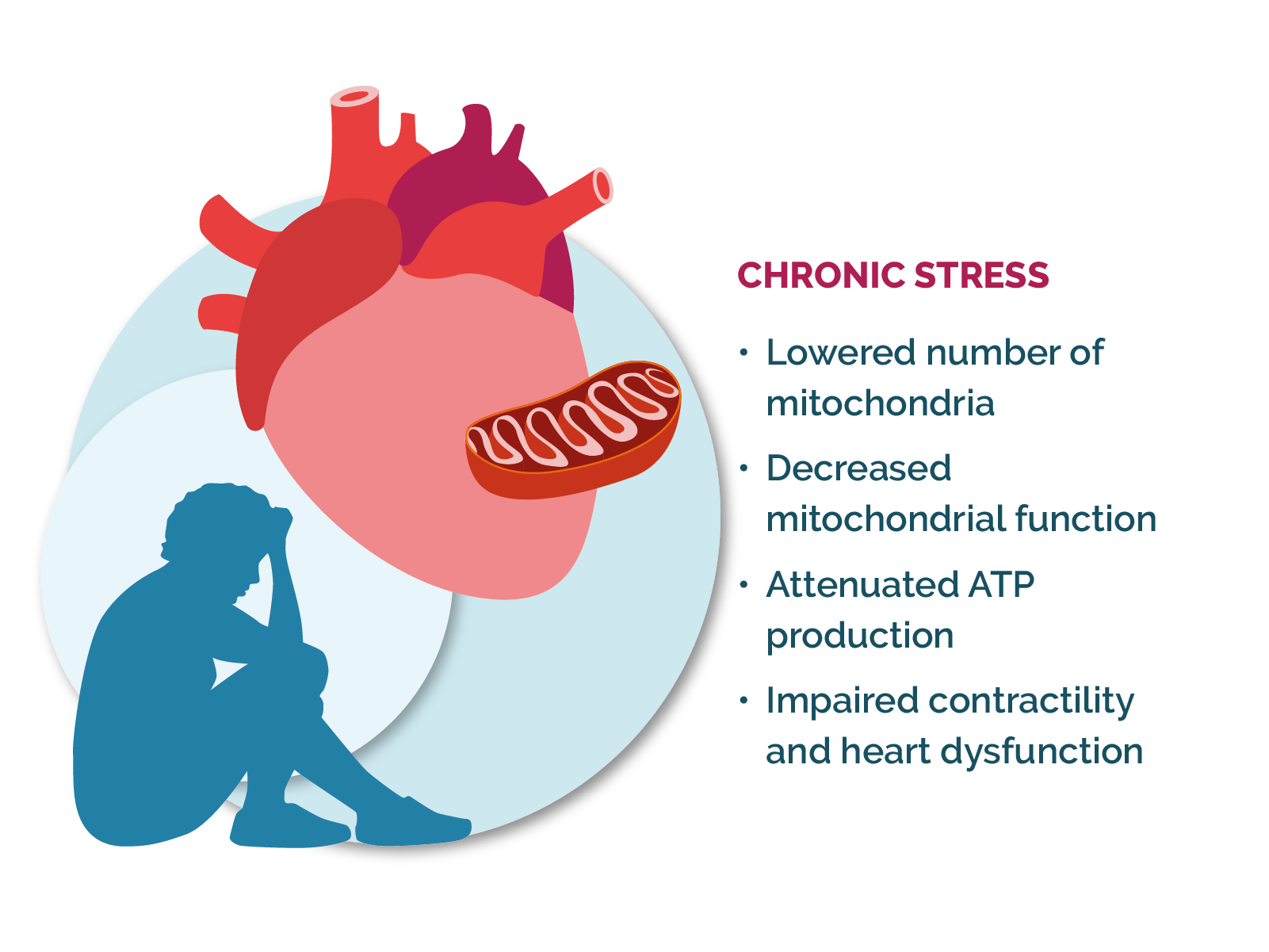

This is where the focus of Essop’s own research lies: the relationship between rising levels of chronic stress in South Africa and cardio-metabolic disease. This is a largely understudied research area and a very relevant one, seeing as South Africa is regarded as one of the most stressed nations globally.

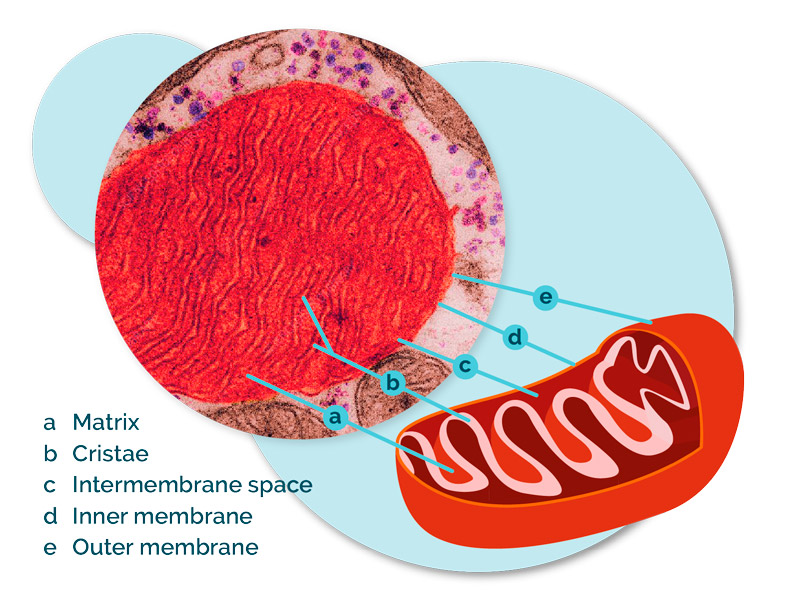

Essop’s work includes looking for mitochondrial protein markers that could offer clues to how cell structures and functions are being changed by stress.

Mitochondria function as our organs’ energy makers, he says. “Mitochondria produce energy called ‘ATP’ [adenosine triphosphate]. This energy sustains the workings of a cell, whether it’s a heart cell, a liver cell, or whatever other cell. But if there is some dysfunction, the mitochondria won’t be able to produce sufficient energy, and the relevant cell shrinks and dies.”

By examining the patterns of how mitochondrial protein markers show up in the cells, scientists are able to identify signs of dysfunction sooner. It can help guide patients to seek earlier screening and intervention and to be monitored to stave off serious illness and death.

But Essop admits that even early detection of cardio-metabolic disease and the supplying of patients with guidelines for lifestyle changes have their limits. This is because of circumstances, contexts, and realities, he says.

“If you’re living in an area with high levels of violence or poverty, or in a household where you can’t buy nutritious food, then the option of resetting your anxiety levels by going for a long walk isn’t always available. This is what we [as researchers] need to be thinking about, instead of just giving advice that people can’t relate to.

“Over time, this kind of chronic stress is normalised but continues to cause dysfunction and increases the chances of developing heart disease. We might hear that someone dropped dead of a heart attack, but really the disease didn’t suddenly occur — it developed over time,” Essop says.

The double burden of HIV and heart disease

Another key area of research at CARMA is the devastating burden of HIV in South Africa and its connection to heart disease.

Over the past 10 years, the link between HIV, antiretroviral therapy (ART), and heart disease has been well established by researchers. South Africa — with its outsized HIV-infected population of an estimated 7,5 million people in 2021, according to UNAIDS — is set to see a correlating spike in heart disease over the coming years.

Prof Hans Strijdom, the deputy director of CARMA, says: “We now suspect that people with HIV, regardless of age, have a two-fold increased risk of developing heart disease. Unfortunately, we have had to rely on data from Europe and North America, so we have never known how applicable research from these countries apply to our situation in sub-Saharan Africa,” he says.

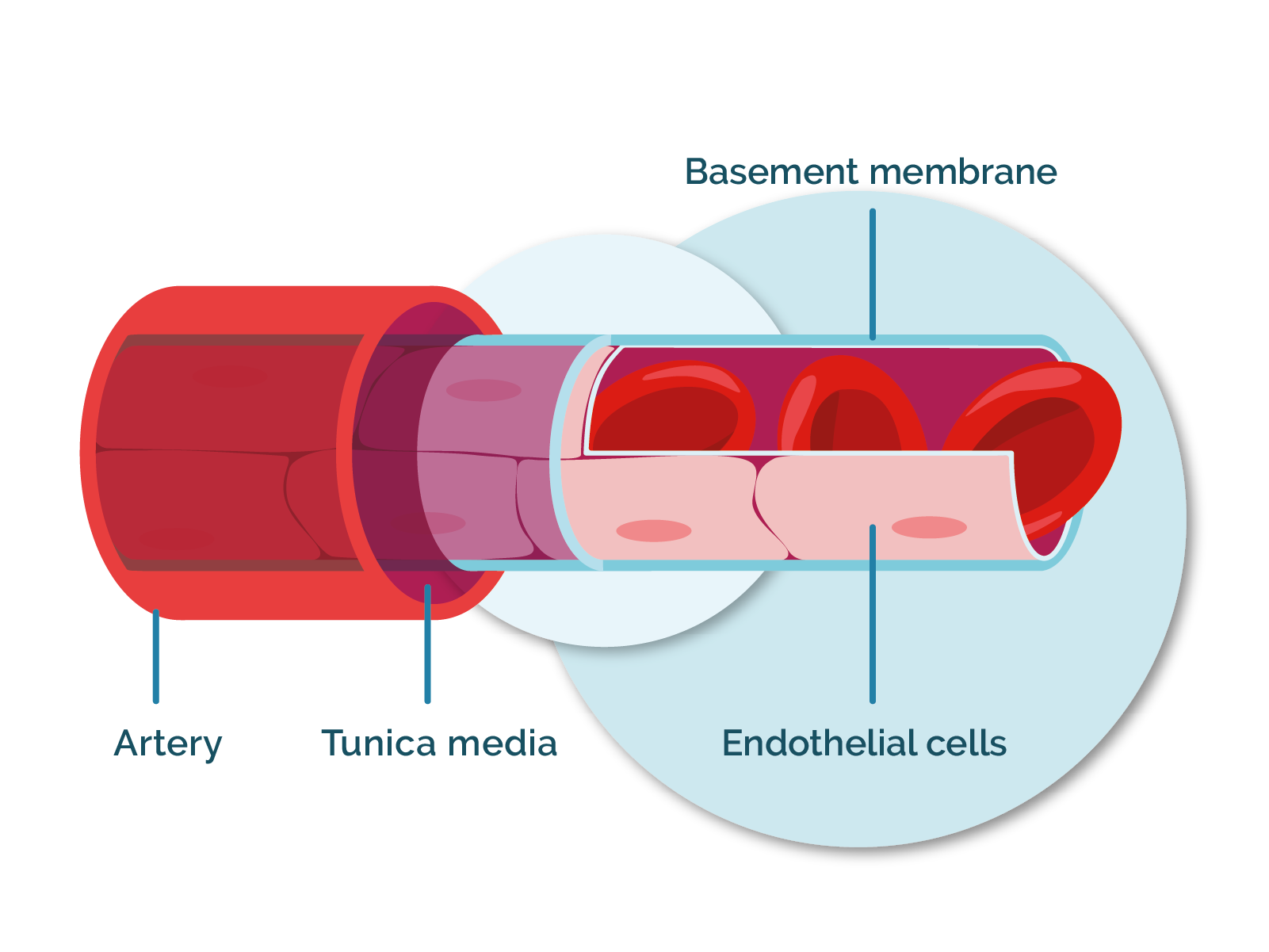

In 2015, Strijdom and his team were able to secure funding from the European Union to research how HIV and ART might cause changes and dysfunction in the endothelium, the single-cell membrane forming the inner lining of blood vessels.

“Endothelial cells are pivotal [to the protection of the body] because they constitute the single barrier between harmful molecules and toxins in the blood, and the rest of the body. Blood is not just the body’s transport system for oxygen and nutrients — it also carries free radicals, fatty acids, and toxins that we want excreted from our bodies.

“Our research evaluates the extent to which HIV and the treatment of HIV affect the layer of endothelial cells, causing it to loosen, develop gaps, and leak. When endothelial cells become dysfunctional or are harmed, those gaps in the cell layer allow harmful things to be siphoned off into the organs, where they cause inflammation and disease.

“The question is whether this might be the origin of HIV patients’ increased susceptibility to heart disease and strokes,” says Strijdom.

Prof Faadiel Essop, the director of CARMA| Photo by Wilma Stassen

The MITO-SAKen research group, led by Prof Hans Strijdom. From left to right: Strijdom, Dr Ingrid Webster, Dr Amanda Genis, Dr Taahirah Boltman, Kheya Mokoena, Dr Marguerite Blignaut, Vuyo Mbombela, Joshua Cambell and Dr Gerald Maarman. | Photo by Elizna Maasdorp

Dr Gerald Maarman (left) demonstrates how to use the Oroboros analyser in the CARMA Metabolic Laboratory. This instrument analyses mitochondrial function. | Photo by Dr Taahirah Boltman

Research for real-world impact

CARMA’s research approach is rooted in public communication and community outreach. Strijdom is unequivocal in his summary of what needs to be communicated in HIV messaging: the importance of knowing your status, not defaulting on treatment, and managing your risk of developing heart disease.

“When we are treating someone with HIV, we must understand that we are not just treating HIV; we must keep in mind that patients are at risk of developing other diseases and comorbidities. We also know that the occurrence of heart disease and strokes will increase over time as our HIV population gets older and stays on treatment longer,” he says.

What the patient management protocol should reinforce, Strijdom argues, is the need for better screening. It’s as basic as doing regular blood pressure and blood cholesterol tests for HIV patients, and listening to their heartbeat, he says.

MSc student Kheya Mokoena (left) and post-doctoral fellow Dr Taahirah Boltman (middle), demonstrating the retinal imaging procedure to a medical student. Retinal imaging, a part of routine comprehensive eye tests, is essential to checking eye health. Problems such as high blood pressure often reveal themselves in the eye first. Retinal images can be assessed for signs of narrowing blood vessels, spots on the retina, and bleeding at the back of the eye.

Retinal eye imaging techniques

As another tool for the early diagnosis of heart disease, Strijdom’s research team is adopting retinal eye imaging techniques that are currently used in optometry. He explains: “A retinal imaging tool can quickly indicate the condition of someone’s blood vessels. It can also help us assess that person’s risk of getting heart disease. Most people will go for an eye test at some point. The optometrist can then take a photo of the retinal blood vessels and Whatsapp it to a specialist in another location who can do the assessment and send back a diagnosis.”

For Strijdom, the beauty of the endothelium is that the early stages of dysfunction are reversible, which means early interventions can slow down the onset of heart disease, possibly even reverse the damage. To him, this is where research can have true impact.

“Sometimes we researchers get so bogged down in our labs, looking into petri dishes, that we forget that it’s not about a molecule or something under the microscope. It’s about doing research that can eventually make its way to a nurse or a doctor who can inform a patient about the steps they can take to prevent heart disease.”

The research ethos that CARMA has adapted constitutes a gear shift. By viewing science and research through the lenses of inequality and socio-historical and political injustices, it is encouraging more reflective and critical thinking among students and staff.

The result, thus far, has been an unveiling of in situ solutions that light the path towards better health for more people.

The research initiatives reported on above are geared towards addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals numbers 3, 10 an 17, and goal numbers 1, 2 and 3 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.