It’s not just about the guns

Anél Lewis

When Renamo leader Ossufo Momade handed over an AK47 rifle to Mozambican president Filipe Nyusi in June this year, it was a symbolic gesture confirming the end of the disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR) process in Mozambique. The international community breathed a collective sigh of relief. Renamo is now formally recognised as a political party, and 48 years of conflict in this region have hopefully come to an end.

But are disarmament programmes, many of them led by the United Nations (UN), doing enough to ensure post-conflict peace in the long run?

The international community has invested heavily in disarmament programmes. Yet, according to the School of Culture of Peace, there were upwards of 33 armed conflicts around the world in 2022, many of them in regions where disarmament and demobilisation have already taken place. Africa was host to nearly half of these conflicts.

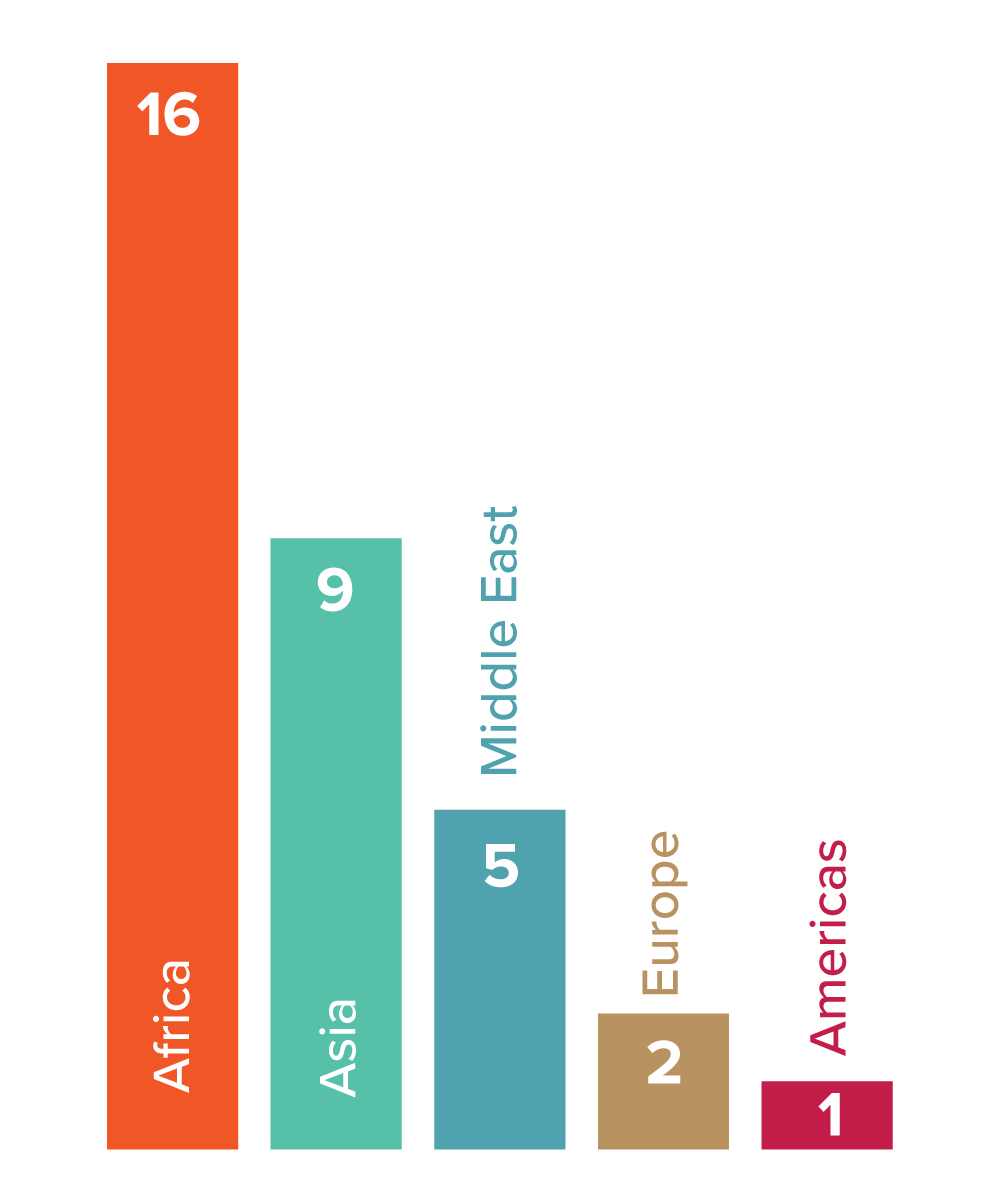

Regional distribution of the number of armed confilicts in 2022

Globally, 33 armed conflicts were reported in 2022 — a slightly higher figure than that in the previous year. Most of the conflicts were concentrated in Africa (16) and Asia (9), followed by the Middle East (5), Europe (2), and the Americas (1). | Source: Alert 2023! Report on conflicts, human rights and peacebuilding

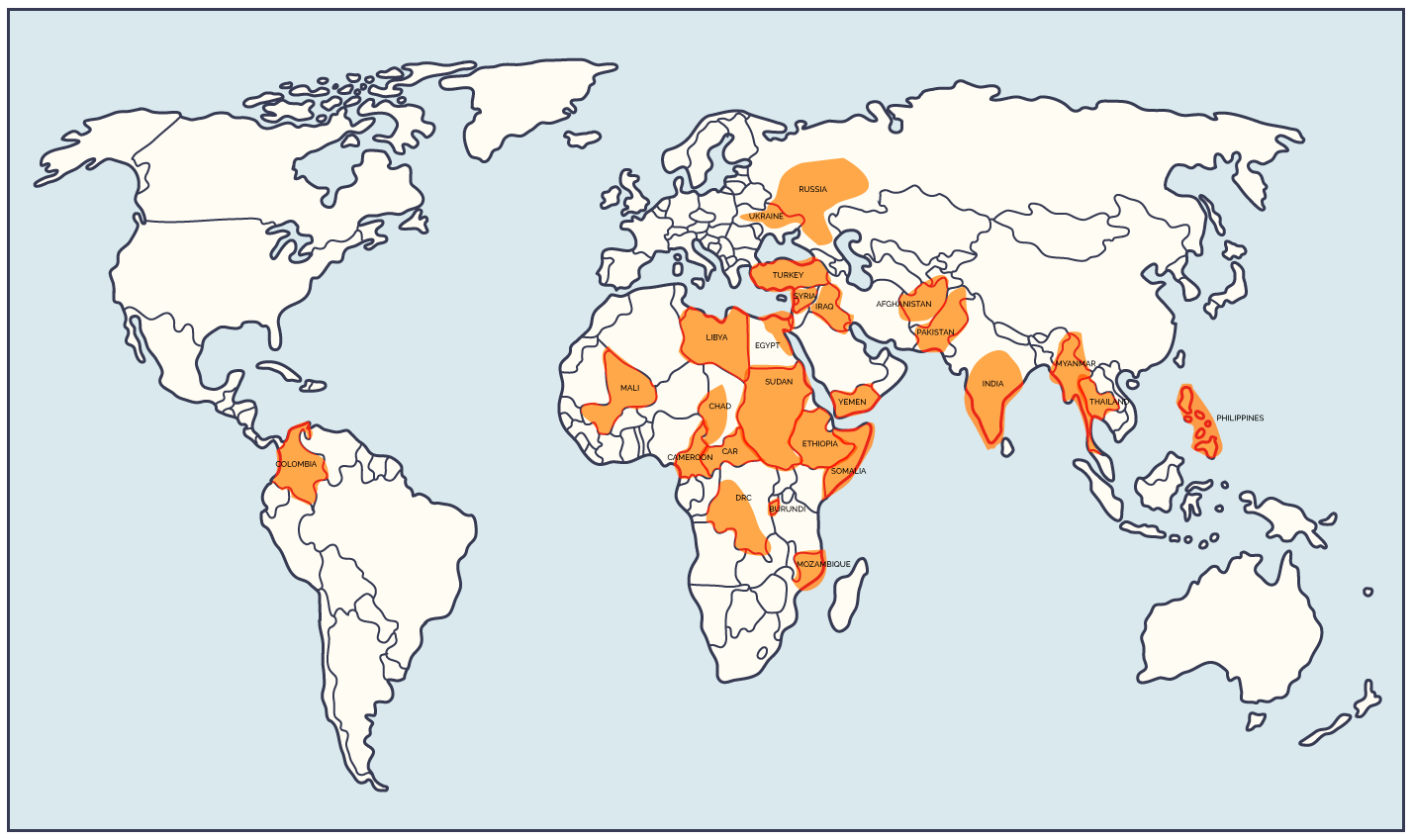

Armed conflicts in 2022

Map showing the relative dispersion of armed conflicts across the globe | Source: Alert 2023! Report on conflicts, human rights and peacebuilding

The question as to why certain disarmament programmes work while others don’t is the focus of DISARM, a 3,5-year-long project on the effect of disarmament on conflict recurrence. Funded by the Norwegian Research Council, the project is a pivotal collaboration between Stellenbosch University (SU) and the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). The institute researches the conditions necessary for peaceful relations between states, groups, and people.

The leader of this project on the SU side, Dr Guy Lamb from the Department of Political Science, has spent more than 25 years researching conflict, arms control, peace building, and violence reduction in Africa. But, he says, the DISARM project is the first systematic global study to look specifically at what causes conflict recurrence after disarmament has taken place. “Disarmament is often approached in a technical way and is seen as a priority by the United Nations.”

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) defines disarmament as “the act of eliminating or abolishing weapons either unilaterally or reciprocally”. With this in mind, Lamb says the focus tends to be on how best to remove weapons from combatants, and how to subsequently destroy them. But there is no work being done on whether the process is effective and whether it has a lasting impact on peacekeeping.

A peacekeeper from the Indian battalion of the United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC) takes stock of weapons and ammunition collected during the demobilisation process in Matembo, North Kivu. | Photo courtesy of UN Photo/Martine Perret

To better understand the conditions under which disarmament can successfully prevent conflict recurrence, the DISARM team has applied a mixed-method research design in collecting data on disarmament provisions in all intra-state peace agreements worldwide between 1975 and 2020. The data makes it possible to quantitatively examine the relationship between disarmament and conflict recurrence by literally counting the incidences where violence reignited. “Currently, little is known about how various disarmament programmes differ or overlap in design and impact,” says Lamb.

The team is now taking the research a step further by applying a qualitative lens to four case studies: Namibia, Mozambique, Indonesia, and the Philippines. “In this way, one can begin to understand how important disarmament is vis-à-vis rebuilding the state and peacekeeping,” says Lamb. Work is already underway in Namibia and Mozambique, with plans to start fieldwork in the other regions towards the end of the year.

The Namibian ‘success story’

The absence of a significant recurrence of conflict in Namibia after close to three decades of war is often hailed as a disarmament success story. While there have been flare-ups — Caprivi secessionist violence in the late 1990s and reports of ongoing violent crime — the situation in the country has remained comparatively controlled after three decades of war ended in 1989, noted SU researcher Haylene Bossau in a presentation at the British International Studies Association (BISA) 2023 Conference.

Lamb attributes this phenomenon to the multi-faceted dynamics that played a part in Namibia’s reasonably successful transition to democracy. Various disarmament processes and government support of ex-combatants helped to reduce conflict. “South Africa’s withdrawal from Namibia to focus on its own democratic transition also certainly helped,” says Lamb.

Mozambique’s ‘fragile peace’

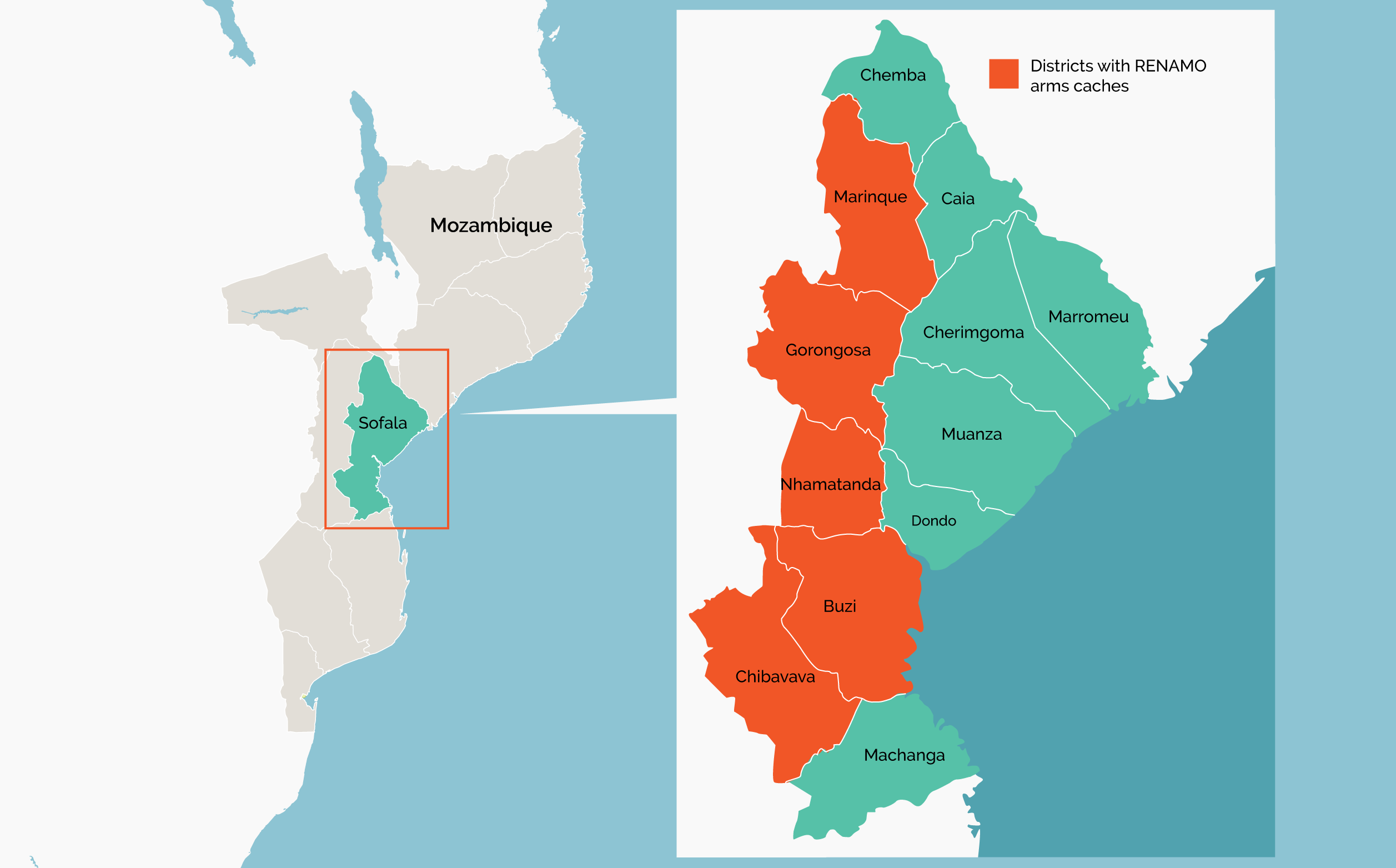

Mozambique, however, offers an example of how disarmament efforts that ticked all the boxes for a peaceful transition can still be followed by conflict. “There was complete disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration, and still weapons resurfaced,” says Lamb.

In SU PhD candidate Monique Bennett’s analysis of the conflict situation in Mozambique over the past 50 years, also presented at the BISA 2023 Conference, she questioned why the country’s warring parties, Frelimo and Renamo, returned to armed conflict even after the UN proclaimed the DDR process a success when the civil war ended in 1992.

Persistent mistrust between the parties posed a challenge to the long-term success of disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR), explained Bennett. She said the mandate was ambiguous, and the UN — faced with timing and resource allocation issues — could only find temporary solutions to the problems. She added that Renamo still had the same access to weapons as it had during the civil war that lasted from 1977 to 1992, and wartime networks also prevailed. The resultant tension between Renamo and Frelimo spilled over into banditry and criminal activity.

Well-intended attempts at DDR can have negative outcomes when coupled with unresolved grievances, Bennett emphasised. “If not done with adequate, careful design or implementation, as in the case of Mozambique, disarmament can create a ‘fragile peace’.”

Largest RENAMO arms caches in Sofala province

The map on the right shows districts with Renamo arms caches in Mozambique’s Sofala province. Renamo is now formally recognised as a political party. | Source: “The fragility of post-conflict peacebuilding: Examining Mozambique’s return to armed conflict two decades post-accord” — a paper presented at the BISA Conference, Glasgow, in June 2023 by Monique Bennett.

Women and war

An often neglected aspect of disarmament — namely the impact it has on women combatants — is another topic under consideration by DISARM.

Of the 33 armed conflicts that took place in 2022, 23 occurred in countries with a low level of gender equality. Yet, gender is a filter not often applied to discussions around disarmament and reintegration, explains Lamb. “We need to understand how women view weapons and what the implications of disarmament will mean for them. Do peacekeeping programmes take the needs of women into account?” Whereas previous studies have looked at women as victims, more needs to be done to investigate the role of women combatants in peacebuilding, he says.

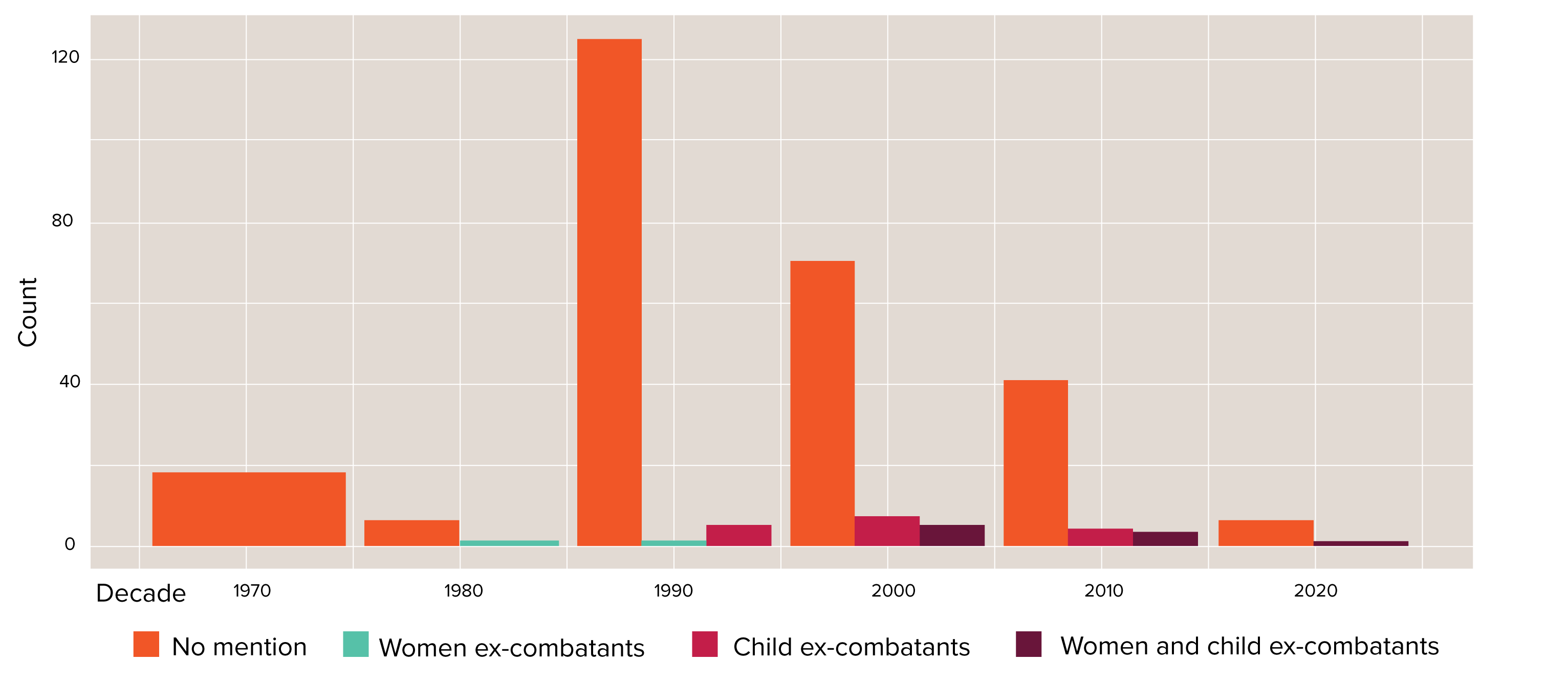

In a conference paper titled “Still lacking representation: Women and minors in DDR provisions (1975–2021", presented at Folke Bernadotte Academy in February this year, Júlia Palik noted: “Women and minors participate in conflict directly as combatants or commanders, and in several different indirect roles. Despite the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) and the UN’s Integrated DDR Standards’ (2006) explicit calls to include women and minors in DDR programmes, both groups remain grossly underrepresented in these processes.” Palik, a senior researcher at PRIO and leader of the DISARM project, adds that, in a study of 126 peace agreements with at least one DDR component each, only 2 made reference to women, 11 mentioned minors, and only 9 referred to both groups. Furthermore, these mentions of women and minors were “essentialist, vague”, with both groups portrayed as victims.

Mention of women and child ex-combatants in disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR) provisions, 1980–2021

| Source: Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

The true power of weapons

One of the focal points of the DISARM project is the symbolism of weapons. “Disarmament cannot merely be a technical exercise,” says Lamb. Programmes need to take into account the myriad of factors at play. Different genders, for example, have different associations with weapons. For men, a gun may be a symbol of masculinity and dominance. For women combatants, having a weapon is a means of asserting their power and establishing an equal footing with their male peers. Disarmament efforts that fail to take this aspect into account could have a profound effect on the women involved, says Lamb.

The symbolism of weapons can even carry through to the national flag. This is the case in Mozambique, the only country in the world whose flag depicts a modern weapon. The AK47 is said to represent vigilance, but for opposition parties, this remnant of the Frelimo flag symbolises violence and civil war.

DDR programmes are deemed to have failed when implementation is incomplete, resulting in weapons not being handed in, or combatants and commanders remaining in contact after conflict has supposedly ceased, notes Lamb. Often, the governments involved are unable to prevent arms trafficking, despite the agreements that are in place. Understanding the impact of the availability of weapons on efforts to secure a peaceful resolution will benefit many contexts, he argues.

A peacekeeper serving MONUC takes part in a training exercise near Bunia in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. | Photo courtesy of UN Photo/Martine Perret

The way forward

The outcomes of DISARM’s fieldwork, as well as the quantitative analysis of peace agreements in the period under review, will contribute to a novel set of policy recommendations that will have concrete applications in regions affected by conflict, says Lamb, even on a local level.

In the Western Cape, for example, where the availability of illegal guns has escalated gang violence in certain areas, the findings of the DISARM project will be highly relevant. Alarmingly, Western Cape Police Oversight and Community Safety MEC Reagen Allen revealed that 699 unlawful firearms were confiscated in only the first quarter of 2023, yet none were destroyed.

“This project will provide critical input to stakeholders in disarmament by providing empirically sound and gender-sensitive policy recommendations on disarmament design,” Lamb concludes.

What about nuclear disarmament?

Apart from those in the DISARM study, the Russia-Ukraine conflict is another clear example of cracks in efforts at disarmament and peacebuilding, especially in relation to nuclear weapons. The military invasion of Ukraine by Russia in February 2022 has caused mass turmoil and upheaval, leading to not only armed conflict but also a larger humanitarian crisis with a significant impact on the global community.

Earlier this year, Izimi Nakamitsu, Under-Secretary-General and High Representative for Disarmament Affairs, reported in a UN Security Council meeting that the risk of nuclear weapons being used in war is currently the greatest since the height of the Cold War. Her comments followed Moscow’s announcement that it would station non-strategic nuclear weapons in Belarus.

Nakamitsu stated, with reference to the war in Ukraine, that “the absence of dialogue and the erosion of the disarmament and arms control architecture, combined with dangerous rhetoric and veiled threats, are key drivers of this potentially existential risk”. On the other side, the Russian Federation argued that there has been a “severe erosion” of global security, with efforts by “victors of the Cold War” to “systematically dismantle key arms control agreements and confidence-building structures”. Also during this meeting, a representative of Brazil said that nuclear disarmament seemed to have “gone into reverse” since the 2020 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) Review Conference.

On the 78th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki (Japan) in August this year, UN Secretary-General António Guterres declared the elimination of nuclear weapons the UN’s “highest disarmament priority”. He also outlined his policy brief on A New Agenda for Peace, which deals with ways to ensure stability in an evolving world. The New Agenda mentions that arms control frameworks have eroded in many regions and calls for a reassessment of disarmament mechanisms and policies.

Armed conflict across the globe

Almost half (16) of the world’s armed conflicts in 2022 took place in Africa, followed by Asia (9), the Middle East (5), Europe (2), and the Americas (1).

Although Russia’s invasion of Ukraine did increase the global number of conflicts in 2022, constituting 9% thereof, the majority (79%) were internationalised internal conflicts.

Source: Alert 2023! Report on conflicts, human rights and peacebuilding

Weapons are big business

- World military expenditure rose by 3,7% in real terms (adjusted for inflation) in 2022. At a record high of US$2,24 trillion, this amounts to 2,2% of the total global economic output.

- Total world military spending accounted for 2,2% of global gross domestic product in 2022.

- The world is manufacturing enough bullets each year to kill nearly twice the number of people on the planet.

- The five biggest military spenders in 2022 were the United States, China, Russia, India, and Saudi Arabia, which were collectively responsible for 63% of world military spending.

Prevention at the global level: addressing strategic risks and geopolitical divisions

Preventing conflict and violence and sustaining peace

Strengthening peace operations and addressing peace enforcement

Novel approaches to peace and potential domains of conflict

Strengthening international governance

The research initiatives reported above are geared towards addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals numbers 3, 5, 10, 11, 16, and goal numbers 1, 2, 11, 12, 13, 14, 17 and 18 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Useful links

SU's Department of Political Science

SU's Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

The Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

The State of the Central Firearms Registry in South Africa: Challenges and Opportunities

ANALYSIS | These gun laws saved 30 lives a month in two big cities. Here’s what it could mean for SA

How to silence the guns in Cabo Delgado

Twitter: @MatiesResearch; @SUArtsSocialSci and @StellenboschUn