More than just words — developing tools to measure early language development

Anél Lewis

How do we know what they know, and don’t? Without a comprehensive set of tools to determine what gestures and, later, words and grammatical structures children typically learn in the first 30 months of life, there is no reliable way to gauge any individual child’s language development.

How do we know what they know, and don’t? Without a comprehensive set of tools to determine what gestures and, later, words and grammatical structures a child typically learns in the first 30 months of life, there is no reliable way to gauge any given child’s language development.

South Africa has 12 official languages — Afrikaans, siNdebele, Sepedi, Sesotho, Setswana, South African English, siSwati, Xitsonga, Tshivenda, isiXhosa, isiZulu, and South African Sign Language (SASL). Each requires their own culturally appropriate linguistic tools for assessing language development. “There are very few tools available in our languages, and those that are available, are for older children,” says Prof Heather Brookes of the Department of General Linguistics at Stellenbosch University (SU).

The solution is not as easy as it may seem: “Translating English instruments to use in other languages is problematic, given the lexical and grammatical differences between languages.”

The lack of reliable assessment tools means that speech-language therapists often do not have any objective, empirical measures of a child’s language ability. Early assessments of language proficiency may prove critical to improving children’s success at school, and ultimately their life chances.

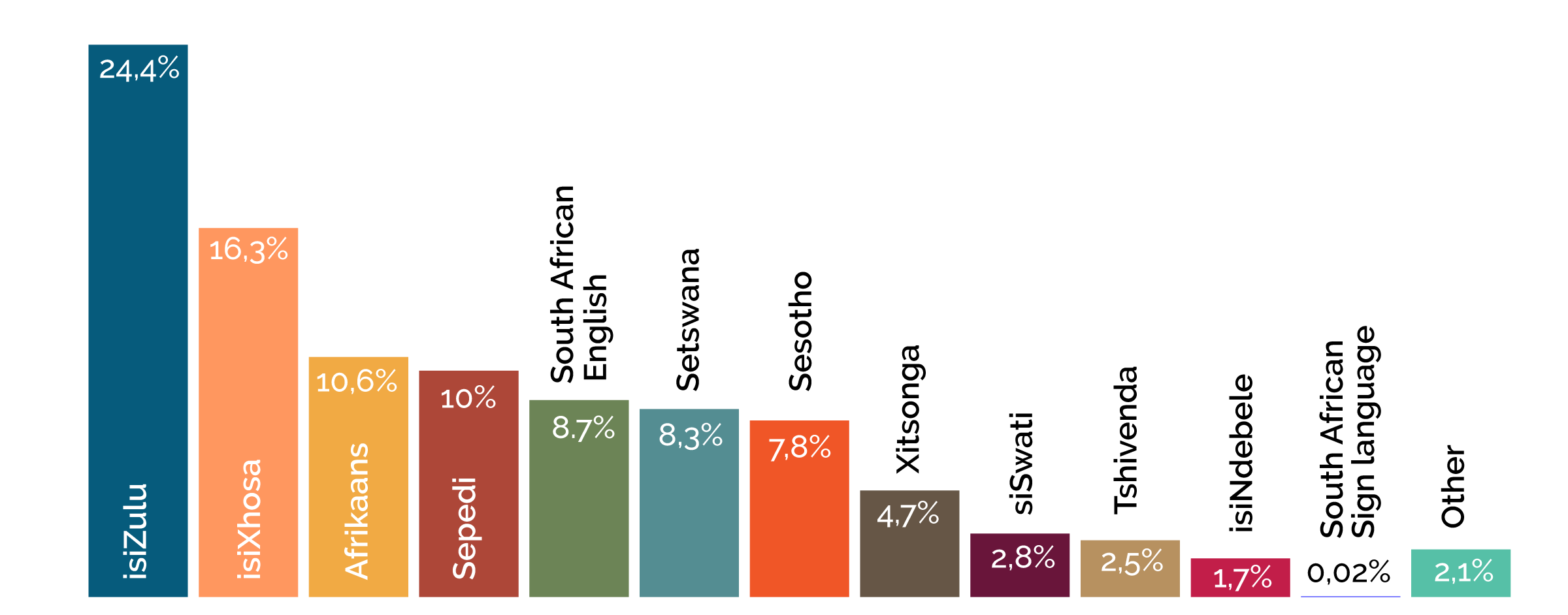

Population distribution by language spoken most often in the household (2022)

South Africa exhibits a unique distribution of languages across the country. In approximately 24,4% of households, isiZulu is the language spoken most often. This remained the case from 1996 to 2022. IsiZulu is followed by isiXhosa (16,3%) and Afrikaans (10,6%). | Source: StatsSA

Gathering the right tools

Children with language delays run the risk of developing learning disabilities, anxiety, and even behavioural problems, says Brookes. However, there is no one-size-fits-all pattern when it comes to language development. It happens differently in different languages. For speech therapists to accurately identify delays in language development, they need to know the norms of child language acquisition in the specific language being acquired. Until recently, however, this type of information was unavailable in South Africa.

Internationally, tools like the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories (MB-CDIs) are used to collect information on the words children learn in different languages and contexts. A CDI is a tool for measuring language development in infants aged 8 to 18 months and toddlers aged 18 to 30 months. Set up as questionnaires or report forms, they are given by speech practitioners to parents or caregivers to note a child’s use of gestures, words, and sentences. Originally designed for American English, MB-CDIs have since been developed into nearly 100 languages around the world, including two in Kenya and two in Mozambique.

SU researchers working in this field note that South Africa’s languages are spoken in cultural contexts that differ significantly from the context for which the original MB-CDIs were developed. Creating a locally relevant set of tools requires more than just the translation of existing English tools.

Until now, there has been a lack of valid, reliable tools to measure language development and to diagnose delays in African languages. “We don’t have the norms of language development for any language in South Africa, not even South African English,” says Prof Frenette Southwood of the Child Language Development Node (CLDN) of the South African Centre for Digital Language Resources (SADiLaR).

Intent on filling this diagnostic vacuum, the CLDN, hosted by the Department of General Linguistics at SU, is working on a flagship project to develop locally relevant CDIs for all of South Africa’s official languages, including SASL.

Prof Heather Brookes is an associate professor in the Department of General Linguistics and the director of the CLDN of the SADiLaR at SU. She specialises in multimodal (speech and gesture) communication and is leading the development of the CDI for Sesotho. | Photo by Stefan Els

The SA-CDI project

The South African Communicative Development Inventories (SA-CDI) project, currently in its third phase, will provide the first comprehensive overview of early-stage language development in this country.

The ongoing study has thus far involved 2 800 children in developing valid instruments for identifying language development norms for children aged 6 to 30 months, in 11 of the country’s 12 official languages.

Around the country, field workers have been collecting information from parents and caregivers about their children or charges’ first gestures, words, and sentences. Parents’ knowledge of their children’s language use is usually fairly accurate, says Brookes.

Overall, the parent report forms are good indicators of communicative development norms. They are especially useful in contexts where children are not accustomed to clinical testing. The data, collected in a culturally appropriate manner using information provided by parents and caregivers, can be used to formulate norms that form the basis of linguistic and cognitive assessments for speech pathologists and therapists to use in their practices.

By the end of 2023, the multi-site team will have validated CDIs for eight languages. In the process of validation, the team looks for correlations between children’s scores, ages, and other variables such as family socioeconomic status. The CDIs for the remaining three languages will be validated in 2024, at which point the team will begin norming with an estimated 22 000 children, at 2 000 speakers per language.

Work will soon start on a CDI for SASL, which became South Africa’s twelfth official language in July this year. The end result will be easy, inexpensive checklists that can be used by professionals to assess children’s language development.

Without a set of valid, reliable tools based on typical developmental norms, there’s a risk of under- or overdiagnosis of language acquisition delay. “At least going forward, if a parent comes to a speech-language therapist, they can say, ‘Let’s do the CDI and see what the child knows’,” says Brookes.

She notes that CDIs have many benefits, “but in particular, administration does not require a qualified psychologist or speech-language therapist, making them ideal for settings with poor access to professionals”. They are also cost-effective to administer at scale, which is beneficial in low-resource settings.

Fields of research explored at the Child Language Development Node (CLDN)

Semantics

Literacy

Gesture

First language acquisition

Second language acquisition

Speech pathology

Language variation

Many different factors affect early language development, says Brookes. Socioeconomic factors (including the parents’ level of education) and a myriad of possible contextual factors such as rural versus city life and monolingual versus multilingual communities all play a role.

In her paper titled “Child Language Assessment Across Different Multilingual Contexts”, Southwood notes that, in many cases, assessment tools are only available in well-studied languages, often those with a “higher social status” or the language of schooling. “For preschool children, being assessed only in the majority language may render misleading results if the language is not spoken in the child’s home and the child has little or no exposure to it.” She cautions that multilingualism needs to be “disentangled from language impairment” as the characteristics may appear similar in young children — children who are exposed to more than one language may appear to lag behind their monolingual peers, similar to a child with a language impediment, if only one of their languages is assessed.

Southwood adds that there is no uniform definition of what constitutes a multilingual child because multilingualism takes so many forms. For example, it can be a result of a child acquiring two languages from birth, or acquiring a second language from slightly later and only to the point of understanding, not speaking it. “All languages could be acquired in the child’s home context or some of them in the community only.”

Multilingualism is the norm in a heterogeneous country like South Africa, Southwood says. There is no single country-wide dominant language. Of the 12 official languages, isiZulu has the largest percentage of home language speakers at 25%. English, despite being the lingua franca, is only spoken as a first language by 8% of the population, notes Southwood. And yet, despite most children not having sufficient exposure to English to be proficient in it when they start school, it is the preferred language of education.

This disconnect between the home language and the language used at school and for learning is exacerbated by the fact that almost half of South Africa’s young children are not at preschool or in professional childcare, and therefore most of their exposure to language occurs at home. Unfortunately, in many cases children are not exposed to activities at home that adequately support language development, irrespective of the language that is spoken, with Southwood pointing out that only about half of children under the age of six are read to or told stories by family members at home.

“Given the variation in the number of languages and the combination of languages, the age of first exposure and the quality and cumulative quantity of exposure to each language, the amount of community support for each language, the language-related expectation in the school system, and the cultural and other contexts in which children acquire their languages, the over-generalisation of research findings and assessment results should be avoided,” notes Southwood.

With this in mind, the team at SU has begun piloting a CDI for bilingual children.

Prof Frenette Southwood, a qualified speech-language therapist, has been a lecturer and researcher in the Department of General Linguistics at SU since 2000. Her work focuses on the development of culturally appropriate and dialect-neutral language tests for South African children, and on language development in Afrikaans-speaking children. | Photo by Stefan Els

Moving forward, collaboratively

The SA-CDI team is currently working on an online CDI app in collaboration with SU’s Department of Computer Science. The app will use pictures, text-to-speech, and a variety of multimodal strategies that will make it easier for parents with different education levels to respond to questions about their children’s language development. “This is already being tested with our own target audiences,” says Brookes.

“We want children to be properly socialised and academically prepared — and they need language for that,” adds Southwood. A good early language development trajectory positively influences later language and school success. Studying a language also contributes to a region’s cultural heritage, and by making sure the CDIs are linguistically and culturally appropriate, the SA-CDI project recognises South Africa’s language diversity.

The CDIs will ultimately constitute valid, reliable tools to diagnose language delays in all official languages, making it easier for speech practitioners to detect any deficiencies before there is a knock-on effect on reading and comprehension, says Southwood.

Moreover, with the CDIs resulting in linguistic norms being available in all of South Africa’s official languages, it will be possible for scientists across the country to assess children’s early language development, and create new assessment tools, interventions, and age-appropriate materials for different learning environments. This will significantly impact literacy and, ultimately, the lives of children in South Africa, she emphasises.

The development of CDIs for language assessment in Africa is a mammoth task that requires a collaborative effort. The SA-CDI project comprises a network of scientists working on language development in different disciplines and departments at the following universities across South Africa: the North-West University, University of Cape Town, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, University of KwaZulu-Natal, University of Limpopo, University of Mpumalanga, University of the Western Cape, and University of Pretoria.

The CLDN is furthermore committed to expanding this work across Southern Africa, and workshops have already been held with researchers in early child language development from elsewhere on the continent.

All the data generated as a result of the SA-CDI project will be hosted by SADiLaR so that it is freely available for future research, concludes Southwood.

During an Afrikaans radio interview, Prof Frenette Southwood and Helena Kruger from SU, and Nina Brink from North-West University speak about the goal behind the SA-CDI project to enable the monitoring of child language development and the timely identification of developmental gaps in South African children. | Source: RSG Taaldinge

Feedback from the field

“Understanding developmental norms is beneficial for tracking individual development and identifying broader trends and challenges in language acquisition,” she says. “It allows for the early detection of language development delays, which, when addressed promptly, can significantly improve a child’s literacy and overall educational outcomes.”

One of the results of the adaptation of the CDIs to a South African context is the realisation that speech practitioners need to be culturally and linguistically sensitive when choosing items for inclusion in a CDI, she says. “This highlights the importance of curriculum developers being sensitive when choosing items to facilitate pre-literacy skills in different contexts. As practitioners, there is a need to be actively involved in curriculum development.”

Ndhambi says that community involvement in the adaptation and validation of the SA-CDIs has raised local awareness about language acquisition and the importance of early identification of language delays. “Early intervention based on accurate assessments ensures that children receive the support they need to develop strong language skills, which are foundational for literacy.”

The research initiatives reported on above are geared towards addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals numbers 3, 4, and 11, and goal numbers 1, 2, and 18 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Useful links

Child Language Development Node (CLDN)

SU's Department of General Linguistics

SU's Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

South African Centre for Digital Language Resources (SADiLaR)

Twitter: @MatiesResearch; @SUArtsSocialSci and @StellenboschUni