Revolutionising the concept of shark management

Wiida Basson

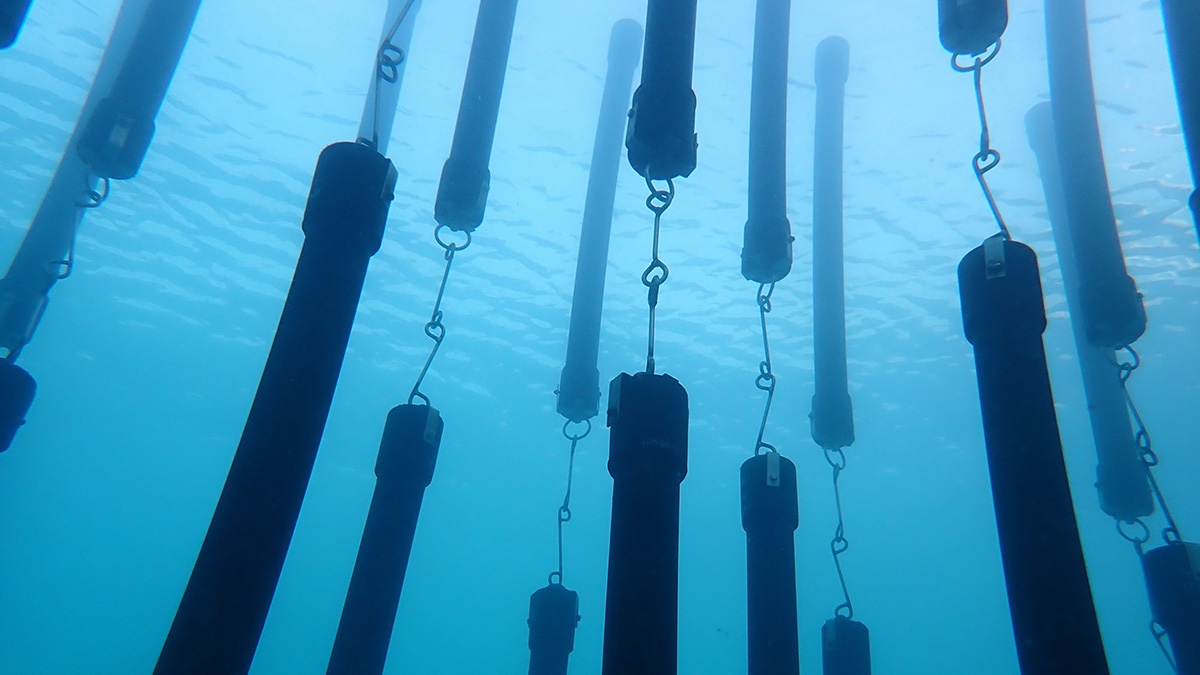

The SharkSafe BarrierTM combines biomimicry of a thick kelp forest with magnetic fields to reduce the chances of shark-human encounters without harming sharks or other large marine species. | Photo by Dr Sara Andreotti

Shark-specific barrier technology developed by marine biologists from Stellenbosch University (SU) and their collaborators has been installed in the Bahamas by a client with a private island in the Bahamas.

In 2011, the Bahamas proclaimed the first shark sanctuary in the Atlantic Ocean and, in 2018, a Marine Action Partnership for Sustainable Fisheries. The installation of the 30-metre-long SharkSafe BarrierTM along a bay on one of the islands will further strengthen marine conservation efforts in the region.

The SharkSafe BarrierTM combines biomimicry of a thick kelp forest and magnetic fields to keep humans at bay from sharks without harming them or any other large marine species. Biomimicry is a practice that learns from and mimics the strategies found in nature in order to solve challenges in the human world.

The nature-inspired SharkSafe BarrierTM technology, 15 years in development, is currently the only eco-friendly alternative to shark nets. The latter "walls of death", in use since 1950, are not shark specific and kill thousands of harmless sharks, whales, dolphins, sea turtles, and large bony fish every year. According to new data published by the government of New South Wales, almost 90% of marine animals caught in shark nets along this Australian state’s coast over the past year were non-targeted species.

Dr Sara Andreotti, extraordinary lecturer in marine biology at SU and a founding director of SharkSafe BarrierTM, says the kelp-like forest created by their barrier technology has been designed to remain in the water for at least 20 years with minimal maintenance required. Eventually, it changes into a reef-like haven for local sea life.

The barrier has been tried and tested extensively in South African coastal waters — from those crashing on the rough, rocky shores of Gansbaai to the sandy beaches of Glencairn — as well as in the tropical waters of Réunion island and the Bahamas. However, the SharkSafe BarrierTM in the Bahamas constitutes the first commercial installation of this technology. Andreotti is now working with coastal municipalities in South Africa to develop alternative funding mechanisms for installation locally, as well as with municipal authorities in Australia and New Caledonia.

Mike Rutzen from Shark Diving Unlimited collects a genetic sample from a great white shark as part of Dr Sara Andreotti’s doctoral research | Photo by Götz Froeschke

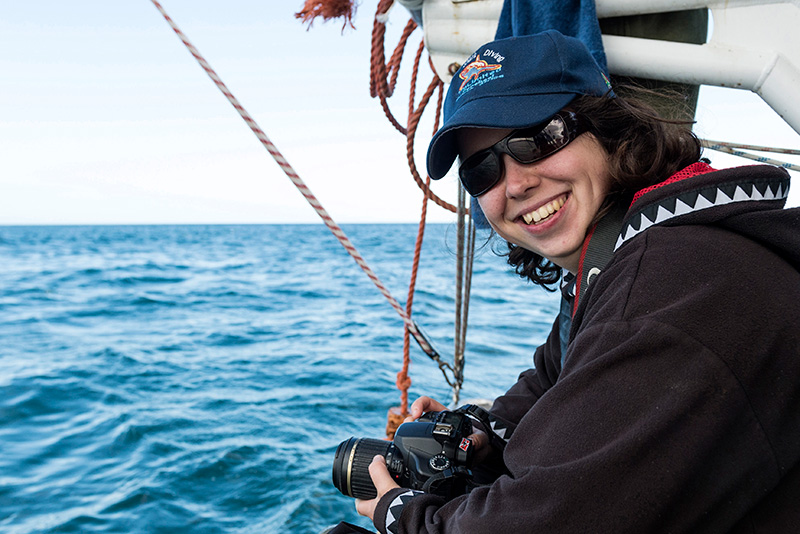

Dr Sara Andreotti on board the research vessel Catalyst in South African waters | Photo by Elsa Hoffmann

Rooted in research

The roots for the development of the SharkSafe BarrierTM can be traced back to Andreotti’s doctoral research on the population numbers and genetic diversity of South Africa’s great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias). Between 2009 and 2011, she conducted the largest yet field research study on this species with the help of the shark conservationist Mark Rutzen. They lived at sea for up to two months at a time to count and collect biopsies from these sharks for genetic analysis.

Between 2009 and 2011, Dr Sara Andreotti collected nearly 5 000 photographs of the dorsal fins of great white sharks frequenting Gansbaai. Each shark has a specific number of notches on the trailing edge of their dorsal fin, essentially serving as a unique "fingerprint" whereby they can be identified. Andreotti manually organised her photographs into a database, documenting the date on which each was taken. After only 400 individuals were identified in the nearly 5 000 photos, finding new ones to photograph proved difficult. | Photos by Dr Sara Andreotti

At the time, the results from Andreotti’s doctoral research painted a bleak picture. Not only did the great white shark population along the South African coastline display the lowest genetic diversity of all such shark populations worldwide, there were also only between 353 and 522 individuals left. According to Andreotti, this was 52% lower than what was estimated in previous mark-recapture studies.

“If the situation stays the same,” she warned during a media conference in 2016, “South Africa’s great white sharks are heading for possible extinction”.

Dr Sara Andreotti worked with an applied mathematician, Prof Ben Herbst, and a software engineer, Dr Pieter Holtzhausen, at SU to develop a custom-made software package that can standardise data collection among great white sharks. The result, IDentifin, enables scientists to compare new photographs of dorsal fins to the existing database of over 5 000 images. In this way, they circumvent the problem of double-counting — identifying the same shark more than once as different individuals.

Among the possible reasons identified for the sharp decline in great white shark numbers was the impact of shark nets and baited hooks implemented on the eastern seaboard of South Africa. Between 1978 and 2008, for example, about 1 063 great white sharks were killed due to shark protection measures alone. Other contributing factors were poaching, habitat encroachment, pollution, and depletion of their food sources.

In the face of these alarming results, Andreotti, Rutzen and Prof Conrad Matthee from SU's Department of Botany and Zoology realised they needed to find an alternative to shark nets — something that would make beaches safer for bathers and sharks alike.

Known global aggregation sites of great white sharks. Question marks indicate suitable latitudinal ranges where great white sharks may occur, but little is known about current population trends. | Map based on data published in PLOS ONE

Inspired by nature

“The thinking behind the development of the SharkSafe BarrierTM was based on a combination of practical experience with sharks and our understanding of their biology and behaviour,” Andreotti explains. Firstly, Rutzen observed how fish and other marine animals such as seals use kelp forests to hide from predatory sharks. This is when the idea of biomimicking a natural kelp forest originated.

This knowledge of marine animal behaviour was combined with existing research on the use of magnetic fields to deter sharks. Most shark species are sensitive to strong, permanent magnetic fields because of the presence of electromagnetic receptors on the tip of their heads. These small, gel-filled pores — called "Ampullae of Lorenzini"— are connected directly to sharks’ brains and allow them to register faint bioelectrical impulses dispersed in the water by their prey.

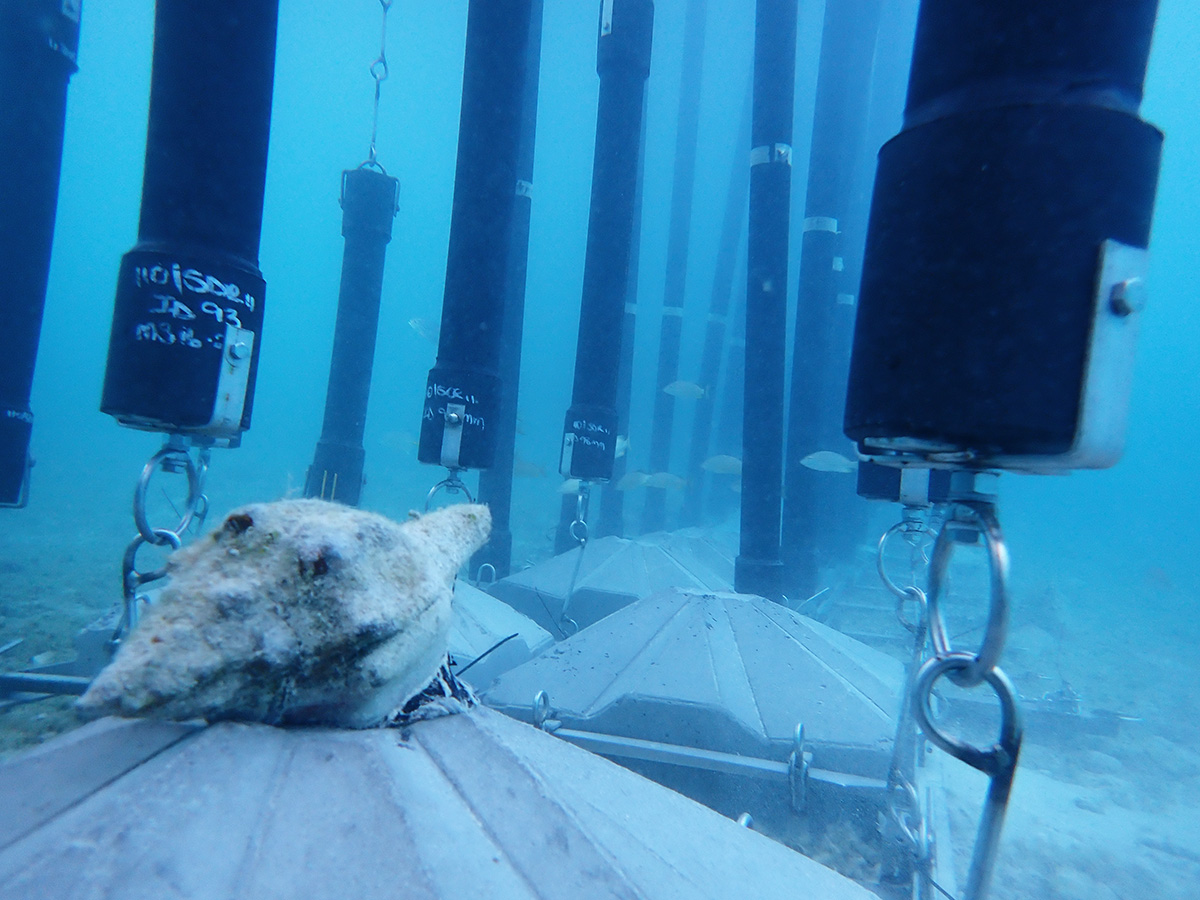

A conch exploring the new SharkSafe BarrierTM installation in the Bahamas | Photo courtesy of SharkSafe BarrierTM

A manatee effortlessly swims through the eco-friendly SharkSafe BarrierTM. While the magnetic field created by the barrier deters large predatory sharks, other animals such as seals and dolphins can freely pass through without risk of entanglement. | Photo courtesy of SharkSafe BarrierTM

During the installation of the SharkSafe BarrierTM in the Bahamas in August this year, local sea life already started settling on the reef-like structure. | Photo courtesy of SharkSafe BarrierTM

Instead of attracting the attention of a shark, the biologists reasoned, a strong magnetic field would overstimulate the Ampullae of Lorenzini and have the opposite effect. In other words, by inserting strong magnets into the kelp-like pipes of the barrier, it would further strengthen the ability of the design to repel sharks.

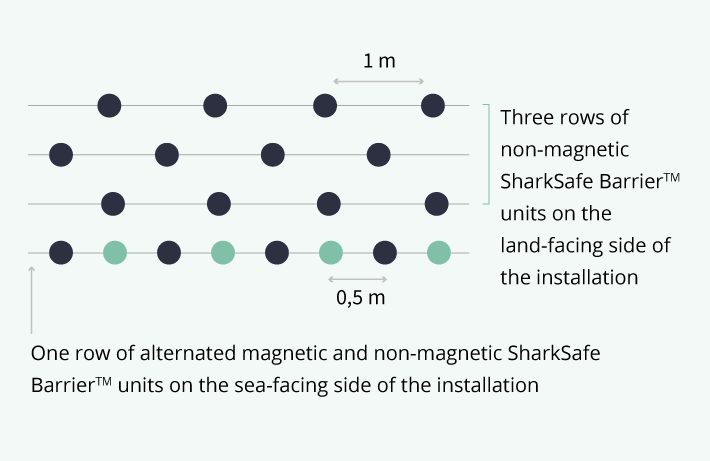

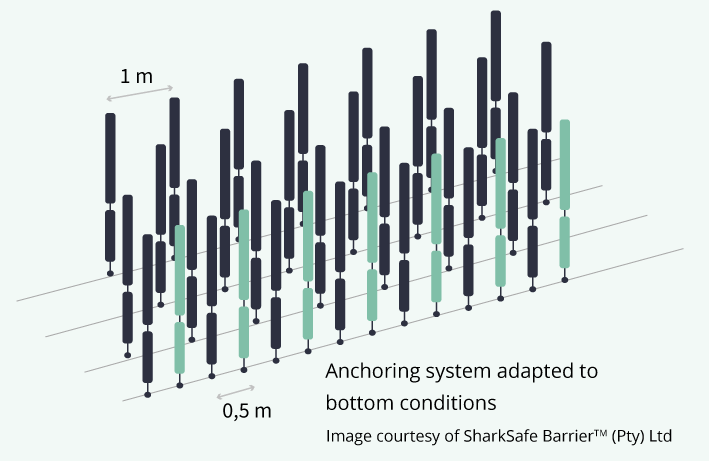

The distance between the land-facing pipes depends on the area of installation. It can be either 1 m or 0,75 m, depending on the specific shark species being targeted. The pipes in the sea-facing row are always 0,5 m apart.| Images courtesy of SharkSafe BarrierTM (Pty) Ltd

The concept was registered as a patent in 2012 through SU’s technology transfer company Innovus. In 2014, the SharkSafe BarrierTM company was commercialised. That was when the real work started. For the past decade, Andreotti has been working with marine engineer Laurie Barwell and other individuals and organisations to not only develop a business model that will attract investors but, first and foremost, to perfect the technology behind the barrier through rigorous testing in South Africa’s turbulent oceans.

Today, the SharkSafe BarrierTM consists of high-density polyethylene pipes manufactured locally by KND Fabrications in Maitland, Cape Town. During installation in the ocean, the buoyant pipes are anchored on a grid-like structure one metre apart from one another, with large ceramic magnets staggered in the ocean-facing row. The grid is then weighted by limpet-shaped 200-kilogram cement blocks and secured by rock anchors and sand.

In 2020, the SharkSafe BarrierTM company really took off when the barrier design was labelled a Solar Impulse Efficient Solution and selected as a finalist in the Smart Eco-Responsible Tourism category of the Tech4Island Awards. In the same year, the inventors of the SharkSafe BarrierTM technology also received the prestigious NSTF-Lewis Foundation Green Economy Award at the NSTF-South32 Awards function. In 2021, the company was recognised by the World Economic Forum’s digital platform UpLink as one of its top ocean innovators.

The SharkSafe BarrierTM team at KND Fabrications in Maitland, Cape Town, shortly after the parts for the 30-metre-long installation were packed into a 6-metre-long container, ready to be shipped to the Bahamas. In the front, from the left, are Laurie Barwell, Errol Bourne, Dr Sara Andreotti, Ronnie Adams, Kezia Bowmaker, and Nina Sirba. At the back are Louie Miggel, Anthony Mederer, Matthew Mtshabe, Lincoln Calbert, Dirk Zimri, Nicolo Farmer, and Ricus du Toit. The factory owner, Rory Bruins, was travelling internationally when the photo was taken. | Photo by Wiida Basson

The pipes biomimic the visual effect of a thick kelp forest. Combined with a series of permanent magnetic stimuli, these pipes will form a barrier that dissuades sharks from passing through. | Photo by Wiida Basson

Revolutionising the concept of shark management

For Andreotti, the first commercial installation of the SharkSafe BarrierTM is the breakthrough that the team has been working towards for the past 15 years. “We now have the technology to allow the rightful inhabitants of the oceans to survive and thrive, and for sea-loving humans to enjoy their time in the water safely,” she says.

This is a win-win situation, especially for areas that rely on ocean recreation as a main source of revenue, such as beach towns in South Africa, Brazil, New Caledonia, and Réunion. In the past, negative encounters with sharks have had adverse effects on local economies.

In April this year, Conservation International’s CI Ventures invested US$250 000 (roughly R4,7 million) in SharkSafe BarrierTM. According to Gracie White, lead of Global Ocean Investments for CI Ventures, lethal control measures for managing sharks are outdated. “It’s time to modernise, for both marine biodiversity and human well-being,” she said in a recent statement.

Hopefully, it’s not too late for South Africa’s great white sharks. According to Andreotti, these sharks have been counted using manual photographic identification in only three studies, the last of which was conducted about a decade ago. “In two of the three studies, it was estimated that there were fewer than 500 sharks left. A more recent study indicated that even the very conservative levels of human-related removal of great white sharks may be sufficient to drive abundance decline, and new mitigation measures may be required to ensure population recovery.

“In contrast, studies based on unconfirmed sightings always risk overestimating the status of the local populations,” she warns.

“We cannot continue to waste time by debating whether the removal of a few individuals by orcas in our local waters could have impacted this population significantly more than decades of human-related, targeted removal with shark nets and drumlines, and the adverse side-effects of bycatch and overfishing of their food resources.

“My fear is that these animals will simply go extinct on our watch.

“It is time”, she says, “for a revolution”.

This eco-friendly installation biomimics the visual effect of a kelp forest, and generates a strong magnetic field through means of ceramic magnets. This forms a double barrier (both visual and magnetic) that keeps sharks at bay. | Photo by Arnault Gauthier

Great whites are the most iconic of all sharks. They are large and imposing but surprisingly elusive, in part owing to their ambush predation techniques. They take advantage of low-light situations (at dawn or dusk) to ambush unsuspecting prey, sometimes by breaching | Photo by Dr Sara Andreotti

The research initiatives reported on above are geared towards addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals numbers 9 and 14, and goals number 2, 6, and 7 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.