A call answered — an international scholar returned home to help leverage Africa’s potential

Desmond Thompson

Prof Umezuruike Linus Opara | Photo by Stefan Els

Umezuruike Linus Opara grew up in a farming village in rural Nigeria and nearly didn’t make it to secondary school because of financial constraints. Yet, he went on to perform so well at university that his bachelor’s degree earned him a scholarship to do his PhD in New Zealand. Later, in 2009, he sacrificed a comfortable teaching and research job in Oman in order to relocate with his family to South Africa — a country he hardly knew at the time — to take up a prestigious DSI-NRF South African Research Chairs Initiative (SARChI) Chair in Postharvest Technology at Stellenbosch University (SU).

These are but a few of the milestones in the incredible journey of this distinguished professor in the Department of Horticultural Science at SU.

The main goal of the SARChI programme is to improve the research and innovation capacity and output of public universities in South Africa, and to deliver high-quality postgraduate students.

Opara has certainly done so during his tenure, having received multiple awards for exceptional performance in terms of research outputs and the delivery of postgraduate students at SU.

Opara, receiving the African Union’s Kwame Nkrumah Scientific Award in 2015 | Photo supplied

Career highlights

Some of Opara’s achievements during his time as SARChI Chair in Postharvest Technology include the following:

- He has established a state-of-the-art research laboratory as a multidisciplinary and inter-faculty research entity, and has developed significant continental and international research networks and partnerships.

- He has (co-)supervised 62 SU master’s and doctoral students, both from South Africa and elsewhere on the continent.

- With more than 381 peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and book chapters to his name, he has a B1-rating from the NRF. This is awarded to researchers who enjoy considerable international peer recognition for the high quality and impact of their recent research outputs.

- In 2015, the Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM) honoured him with its Impact Research and Science in Africa Award, which recognises outstanding scientists making significant contributions to agricultural research for development in Africa.

- Also in 2015, he was a continental laureate of the African Union’s Kwame Nkrumah Scientific Awards for Scientific Excellence, which honours senior researchers who distinguish themselves through their contribution to African development.

- In 2019 and again in 2021, Clarivate’s Web of Science platform included Opara as a “highly cited researcher”, an accolade reserved for scientists who produced multiple papers ranking in the top 1% by citations within their field and year of publication.

Agricultural engineering

Opara earned his academic qualifications in the discipline of agricultural engineering, which applies engineering principles to the design, development, and improvement of agricultural processes and products.

Agricultural engineers play a vital role in ensuring the global food supply while also promoting environmental protection and the sustainable use of bioresources (the living-based matter that results directly or indirectly from photosynthesis and is of use to humans). They work to develop new technologies and practices that help farmers produce more food more efficiently. They also work to improve the sustainability of agricultural systems so that farmers can continue to produce food for future generations.

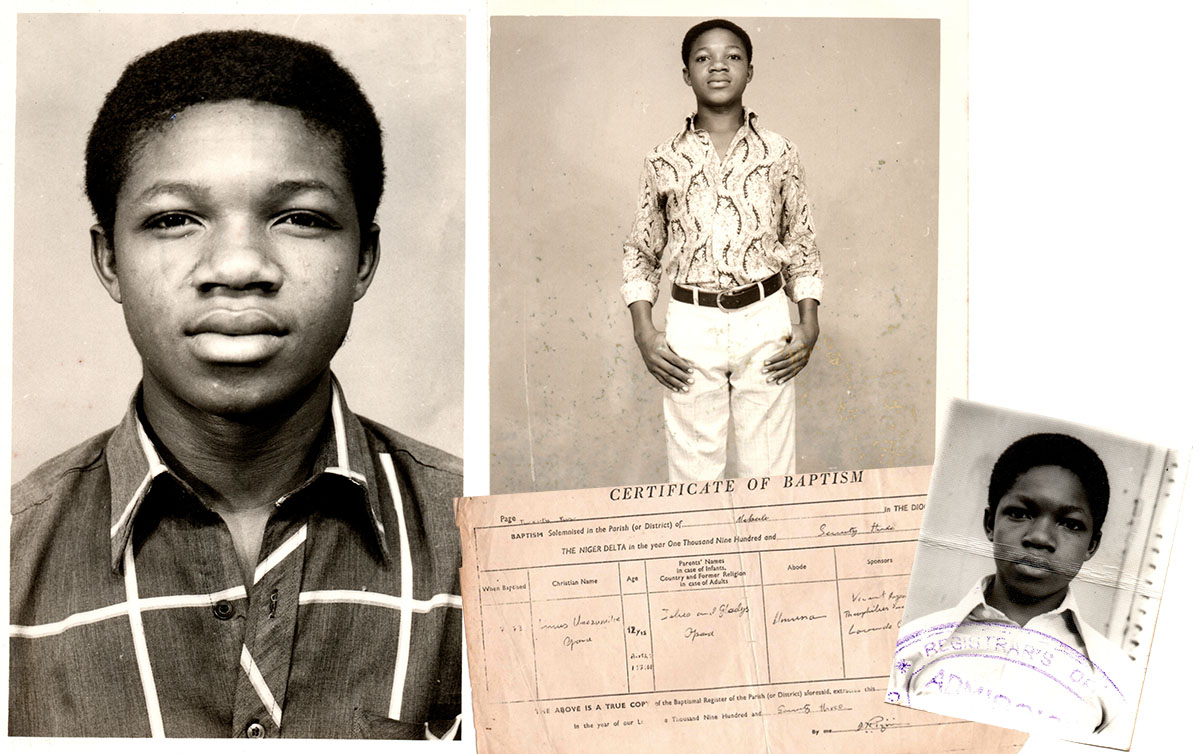

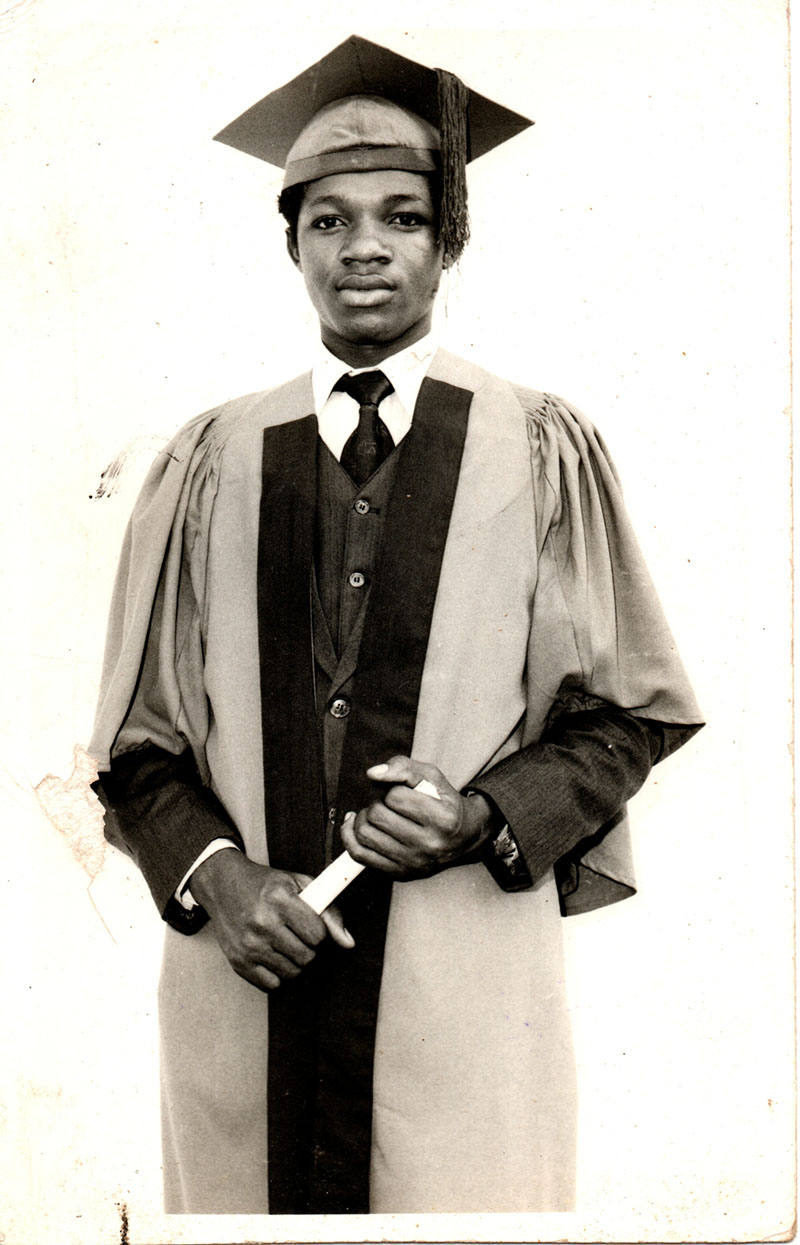

Young Umezuruike grew up in a farming village in rural Nigeria. After nearly dropping out before secondary school because of financial constraints, he went on to complete his PhD on a scholarship in New Zealand. | Photos supplied

Cutting too close to the bone

Opara traces his interest in food security back to his formative years.

“Agriculture was all I knew. There were no industries where I grew up [in Umubachi village in the vicinity of Owerri, capital of Imo State in South East Nigeria]. I never went to a city until I was 18. That’s just the way it was.”

Growing up, he did not see much of his father, Julius Uzoma Opara, who worked in the city in order to earn money to support the family back home. He was, however, very close to his mother, Okaraonyemma Gladys Opara, whom he helped on the farm from early on.

Opara was five years old when the newly independent Nigeria’s first and second military coups took place in 1966. This was followed by civil war, which broke out in 1967 and raged until 1970. Up to 100 000 combatants died in the fighting, and it is estimated that famine claimed the lives of as many as 2 million civilians.

“The children were the worst. They were so thin, their bones were like sticks. Their stomachs were swollen with hunger,” writes author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in Half of a Yellow Sun (2007), a fictionalised account of the devastating Biafran War.

Opara’s own experience bears out reports that hunger and starvation were prevalent in the region at the time.

“I remember, as a little boy, waiting in the village for a day or two for my mum to come back with food, not sure whether she would make it. People were not able to cultivate; they were not able to trade. I remember my parents moving the entire family from one village to another and from one bush to another as the fighting came closer and closer.

“There was kwashiorkor [severe malnutrition caused by a lack of protein]. Some of my age mates died. Not from any other disease, but because there was a lack of food. So, when we now talk about food security, I feel it myself.”

Opara’s mother, the late Mrs Okaraonyemma Gladys Opara | Photo supplied

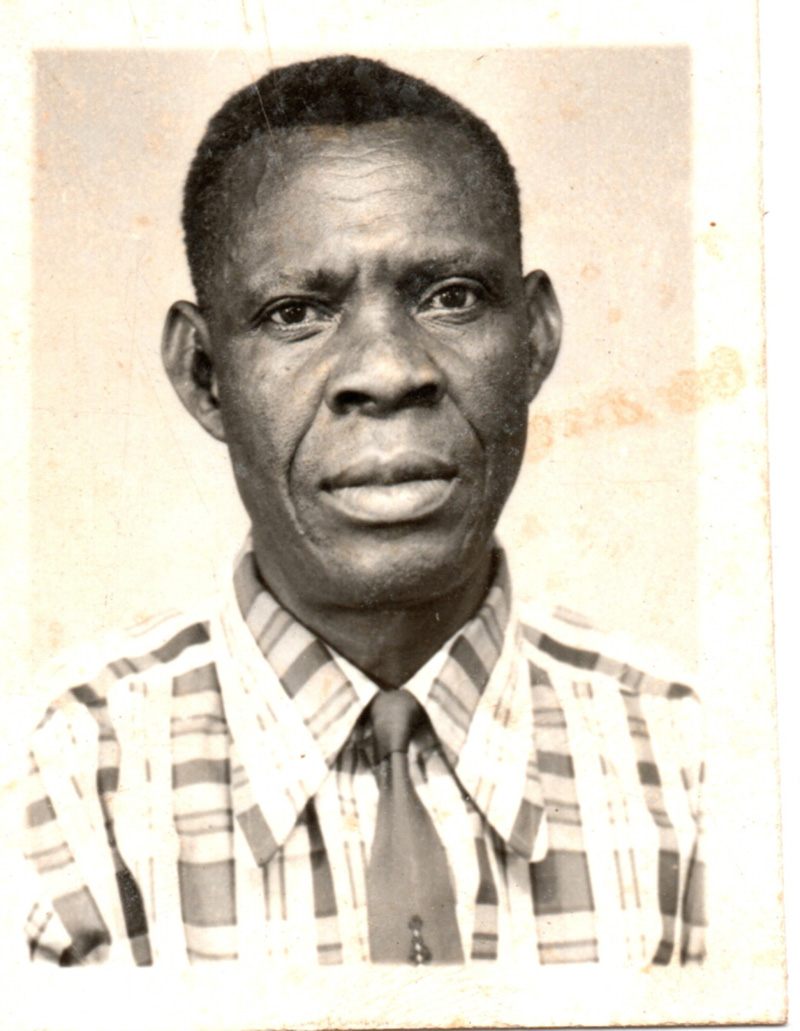

Opara’s father, the late Mr Julius Uzoma Opara | Photo supplied

A desire to learn

When young Opara finished primary school, his mother asked him to help her at home because the family could not afford to send him to secondary school.

The boy did so, but pleaded with his mother to make a plan because “I needed to go to school".

“She promised me that if we sold some of our produce, she would do so. And that’s what we did. She often sent me to the market to sell farm produce — such as yams, cassava and other vegetables, and palm kernels — and she’d put some money aside in a calabash jar. When it was full, I was able to go back.”

Opara finished school, but calamity struck again: Examination results were withheld because some students had cheated. He went to his father in the city of Yola in the northern part of Nigeria and asked for money to register again. He was told, however, that there simply wasn’t enough, and that he would have to look for work.

“I cried for weeks, but my father said, ‘Son, you can complain about the bed somebody gives you to sleep in, but if you get a pinch on one side at night and don’t turn over, you’ve only got yourself to blame.’ So, I found a job as a sales assistant at an ironmonger’s store.

“I sold nails and floor tiles and so on. I opened a bank account and deposited my salary there. After about a year and a half, it was getting enough. So I wrote the exams as an external candidate and passed. I withdrew all my money, resigned from work, and enrolled at university.

“I knew I wanted to do a course related to agriculture, and when I saw I could combine it with engineering, my mind was made up. So, I did my five-year degree in agricultural engineering at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

A ticket to change

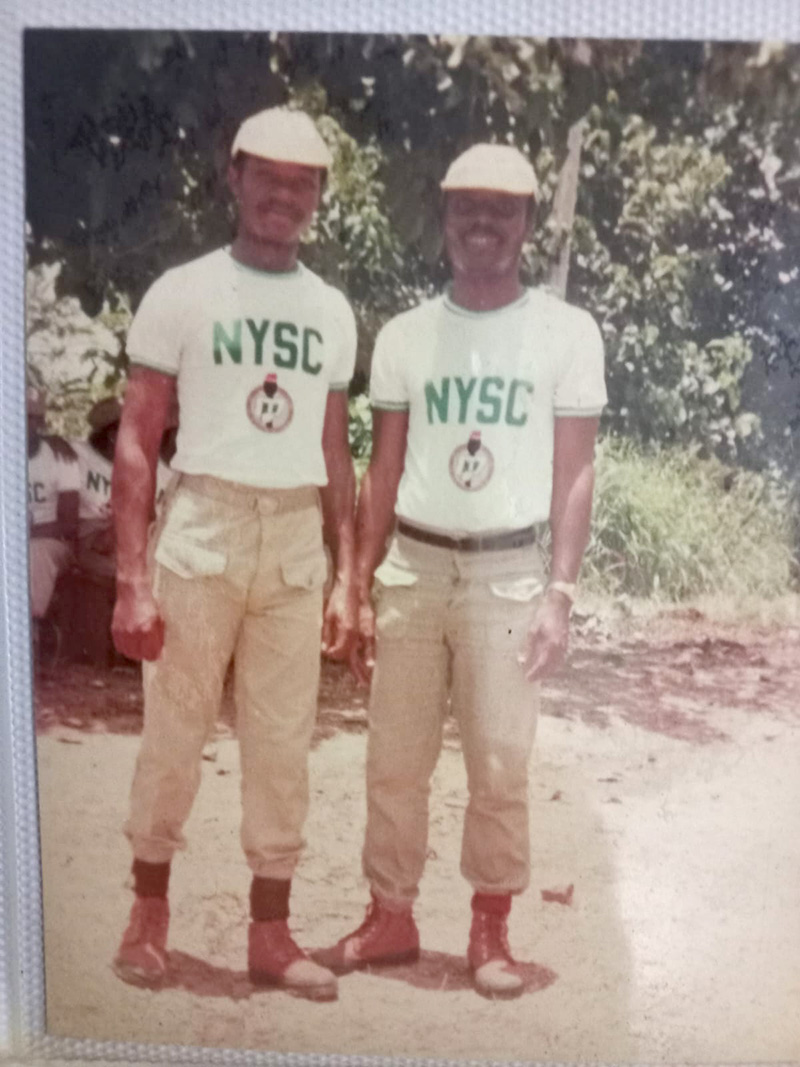

“I got a first-class pass, and then had to do national youth service, which was obligatory after the civil war. One of my engineering lecturers who would later become my master’s supervisor, the late Prof Uche G.N. Anazodo, arranged for me to join the National Centre for Agricultural Mechanisation.

“They sent me to do a survey on appropriate technology for rural women in the five eastern states of Nigeria. It was then that something happened that would change my life.

“Out in the field one day in the city of Enugu, I saw a sign for the British Council. It was hot and I was tired, but I decided to walk there because I knew they would have a library. It was nice and cool inside with air conditioning.

“The first booklet I opened had an advertisement for PhD scholarships for New Zealand citizens who had earned a first-class degree. I took down the details and wrote them a letter that night, saying, ‘I am not a New Zealand citizen, but I did get a first-class pass’. Two months later, I heard I was accepted! But I had to get myself over there.

“I tried to raise the funds, but had no luck. I wrote again, and they agreed to sponsor me a ticket from London to Auckland. But I still couldn’t raise the funds to fly to London.

Umezuruike with his school leaver's certificate, his passport to university| Photo supplied

Umezuruike (left) with an unnamed friend during their national youth service in Nigeria in 1987 | Photo supplied

Helping hands

“So, I went back to Nsukka to do my master’s. I finished my first project in record time, and was given another, this time on computer modelling for agricultural mechanisation, although we didn’t even have a computer in the department!

“I made a friend in [the Department of] Electrical Engineering, where they had a PC — the smallest one money could buy. We struck a deal with the technician that looked after it. He would lock us in with it at night, and open up again for us early in the morning before the other staff came in. We went every night, carrying a bucket of water in which to put our feet to stay awake.

“I wrote my thesis. The defence went well and I got my degree. But I still had that scholarship and the ticket to Auckland. I just had to get to London. So, I went to see an uncle of mine who was a technician at a flour mill.

“He said, ‘Why didn’t you come to me before?’, took me to a restaurant for a nice meal, and then gave me the money. He said he didn’t want it back, but I had to go immediately. I just rushed to my village to greet my parents, and I was off.

“I didn’t know what to expect. I even packed a roll of toilet paper, just in case!”

It turns out Opara needed another flight ticket, one to get from Auckland to Palmerston North. Fortunately, he received assistance from his new department and made it to Massey University just in time, on the very day his long-delayed scholarship would have been cancelled had he not taken it up.

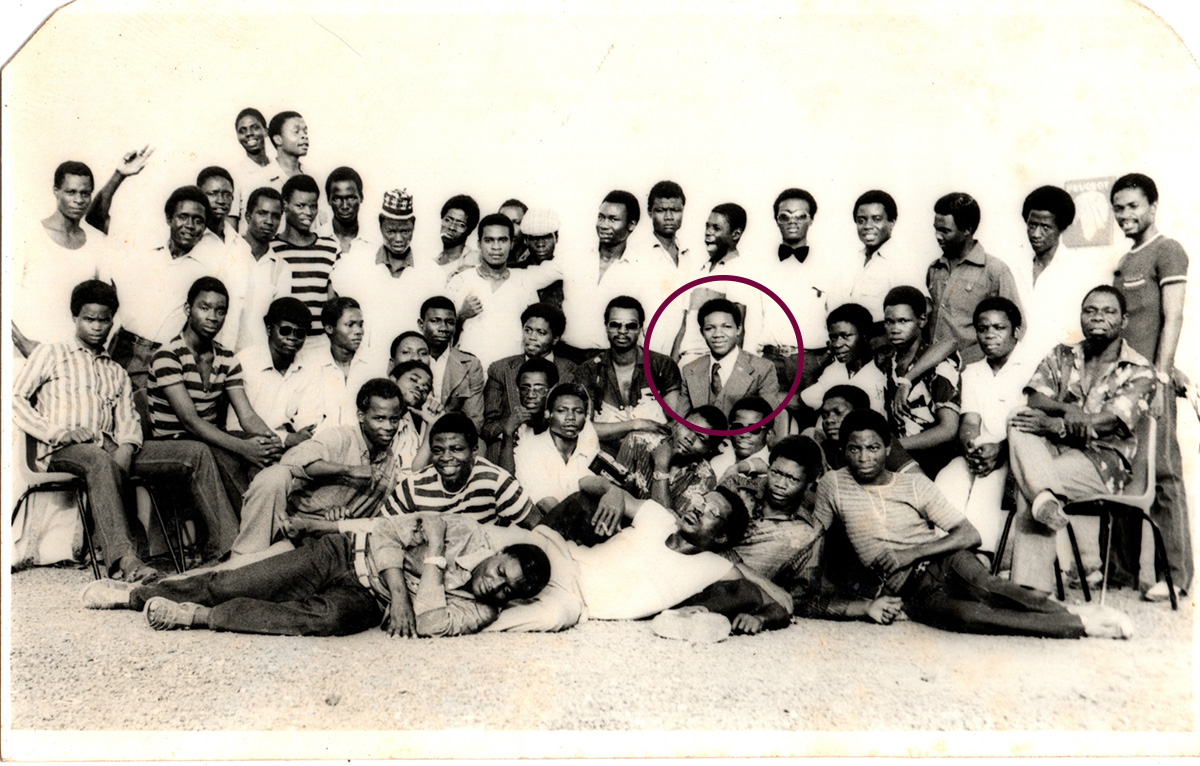

Staff members of the United Trading Company of Nigeria, where Umezuruike found a job after school to earn money so he could further his education. He is the dapper young man in a suit and tie in the centre. | Photo supplied

Tree of knowledge

It was at Massey that Opara started specialising in postharvest technology.

“In Nigeria, all my research and practical experience had been in mechanisation and computer modelling, but in New Zealand, I was exposed to what happens after harvesting. It was very practical, with good interaction with industry.

“My supervisor, Prof Cliff Studman, took me to an orchard in Hastings [two hours northeast of Massey University]. It was the first time I saw apples. I had read about it in the Bible, but hadn’t known if it was just a story.

“So, I raised my hand and actually picked one, but I wasn’t sure how to eat it. Then I saw my supervisor rub the apple he had picked on his trousers and take a bite, and I copied him.”

For his PhD, Opara was asked to investigate the problem of cracking and splitting in apples, which occurs primarily in the orchard but also at packhouses and during transportation.

“It’s a quality control issue because when the fruit becomes cracked, opportunistic pests and diseases can get inside and spoil it,” he says.

The South African connection

It was this research of Opara’s that would later put him on the radar screen in South Africa.

“Years later, when I was awarded the SARChI Chair and arrived in Stellenbosch, industry sought me out because, by then, I had published quite a bit on cracking and splitting.”

Henk Griessel, quality assurance manager at Tru-Cape Fruit Marketing, South Africa’s largest exporter of apples and pears, confirms this account.

“I was very excited when I first heard there was a new apple guy in town because that’s my bread and butter. With his specialist knowledge from New Zealand, I knew he could help us reduce our risk rating as a country so that we could become the world’s first choice,” Griessel says about Opara.

“He had very strong academic credentials with an engineering background — a new facet in our industry, which tends to be dominated by horticulture graduates. He brought novel problem-solving skills, which strengthened the whole postharvest scene in our country.”

Heeding the African call

So, how did Opara end up in South Africa?

“That’s an interesting story,” he says.

“After completing my PhD, I got a job at Massey as a lecturer in postharvest engineering, did some work for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in Rome and Iraq, and was then appointed at Sultan Qaboos University in Oman.

“I got quite involved in development work in Southeast Asia. It was at a conference in Vietnam, after giving a presentation, that someone came up to me and said, ‘Brother, you must come home. Africa needs you.’

“I didn’t know this white lady, but in time she would become a sister. That was Prof Lise Korsten of the University of Pretoria, and we became friends,” Opara says.

Korsten, the co-director of the DSI-NRF’s Centre of Excellence in Food Security, agrees: “I was listening to him and I thought, ‘My goodness, this guy’s brilliant. Why is he not in Africa?’ I mean, this is our brother. And he was training students and doing brilliant research. And I thought, ‘He must come home!’ And that’s why I went up to him.”

Opara continues the story: “I later organised a postharvest conference in Oman and invited Lise as keynote speaker. She told me the South African government had launched a research chairs initiative, and encouraged me to apply. I did, and eventually succeeded — through Stellenbosch.”

The winning proposal

Opara’s pitch was to investigate technological innovations in the postharvest field that could support the South African agricultural and horticultural industries.

“Given my background in engineering, my proposal was to look at cold chain management. Packaging is a critical component of that. Around 12% of the cost of a shipment of fruit or vegetables or flowers can be ascribed to packaging alone. So, if you could optimise your packaging with modelling and experiments, you could enhance your profits.”

There was a two-year delay before Opara took up the position he had been awarded. This was partly because he had to sort out his affairs in Oman, but there was another reason as well.

“I didn’t know Stellenbosch and people said it would be hard for outsiders. I was bringing my wife [Gina] and two daughters [Ijeoma and Okaraonyemma], so I had to make sure it was the right thing to do. But it was a good opportunity to get back into research and return to Africa, so I said, ‘Let’s go!’”

Was it the right decision?

“It was hard initially. We didn’t know anybody and everything was unfamiliar. But it all worked out in the end, and now we are at home in Stellenbosch. South Africa is home now.”

The Oparas in Victoria Street, Stellenbosch. From the left: Ijeoma, Gina, Umezuruike, and Okaraonyemma. | Picture by Stefan Els

Better together

Still, it took Opara some time to settle into his role at SU.

“I used the first year or two to learn the ropes. I walked around on campus, interacted with people, attended seminars, gave guest lectures and so on. I’m based in the Faculty of AgriSciences, but I also reached out to [the faculties of] Engineering and Medicine and Health Sciences and so forth, and everyone said, ‘Absolutely, let’s work together.’

“I followed an interdisciplinary approach, perhaps because engineering is an applied science. Instead of trying to go it alone, we collaborate to effectively deal with the complex challenges facing us. And that became one of the strengths of our chair,” Opara says.

One of his closest collaborators over the years has been Prof Willie Perold, a former Vice Dean for Research at the Faculty of Engineering and another avid supporter of interdisciplinarity.

“The magic happens when you get a broader view on the problem thanks to people from other disciplines working with you. That’s when you find innovative solutions,” Perold says.

Opara also made sure to extend his collaboration beyond the confines of research.

“I engaged with key industry role players, attended board meetings, and visited orchards and packhouses. I reached out to industry because relevance and impact are important factors in research. The solutions that we develop in academia must solve practical problems for industry, for society at large.

“So, some of my first trips outside of Stellenbosch were to Ceres, Citrusdal and Grabouw to understand the horticulture industry and agrifood systems there.”

The road ahead

Opara’s SARChI Chair comes to an end in 2024, but he wants to continue his work promoting science in Africa.

“I see myself travelling a lot on our continent, making my contribution by demonstrating what is possible through the work we’ve done via the SARChI Chair.

“I would like to use my networks on our continent to promote the idea that it is possible to solve Africa’s problems if we get the policies right, make the required investments, and build the necessary capacity. This is what the NRF and the South African government did with SARChI,” he says.

Perold agrees about the value of the initiative: “SARChI has been fantastic – South Africa and its public universities, but also for the rest of the continent. The number of people trained in highly skilled working environments has been significant. We need more of that.”

The last word belongs to Korsten who, all those years ago, urged her African brother to come back home: “I’m just so glad he did, bringing his knowledge, experience, and energy with him. And I can tell you, he’s made a significant difference. He’s had a huge impact with his research and in training the next generation of African academics.”

Whats in a name?

“My parents called me ‘Umezuruike’ when I was born. In Igbo, ‘ume’ means ‘breath’ or ‘heart’ and ‘zuruike’ means ‘to ‘rest’ or ‘be at peace’.

My mother [Okaraonyemma Gladys Opara], who gave birth to 10 children, had lost many before me, so when she was pregnant with me, she said something like, ‘This one must stay; let my heart be at rest’,” Opara explains.

“When I was first baptised in the Roman Catholic Church as a baby, there was an Irish priest who insisted that I must be given an English name and suggested ‘Linus’, because he was the second Bishop of Rome, after Peter.” (Opara was also baptised a second time, as a teenager in his family’s Anglican Church.)

“So, ‘Linus’ became my English name, and throughout most of my school years, it was always ‘Linus’ first, then ‘Umezuruike’.

“But then I started thinking about it, and I thought, ‘No, my first name should be what my parents called me.’ So, I started putting ‘Umezuruike’ first. Some people kept calling me ‘Linus’ first, and that is also fine. It was a personal thing to put ‘Umezuruike’ first.

“Professionally, I’ve tried sticking to ‘Umezuruike Linus Opara’, but some journals don’t accept a middle name, and many people know me as ‘Linus’. But I always try to use ‘Umezuruike’ as well because that’s my real identity. It’s a family thing, with some history to it.”

The research initiatives reported on above are geared towards addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals numbers 1, 2 and 5, and goals number 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Useful links

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

Twitter: @MatiesResearch and @StellenboschUni