Research with real-world impact

Desmond Thompson

Illustration by Ronel van Heerden | Original photo by Stefan Els

Stellenbosch University currently hosts 50 research chairs, 20 of which form part of the South African Research Chairs Initiative (SARChI), funded by the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI), through the National Research Foundation (NRF).

Servaas van der Berg, a professor in economics recently retired from Stellenbosch University (SU), had a lightbulb moment while visiting a primary school in Limpopo, the country’s northernmost province, in the early 2000s.

Early days

“We were busy with a survey, testing children at a government school — typical Grade 6 learners, giggling at the presence of outsiders in their classroom. They had to answer basic maths questions like 7 x 17. It soon became clear that they had not been taught multiplication. What many did was to draw 17 lines and count them seven times, often still getting the answer wrong,” he explains.

“I looked at those kids and realised that at the age of 12 or so, they were already excluded from the future economy. They had devised their own clever workaround, but it would not sustain their progress for long.

“There was only a slim chance that they would get into university or land a good job one day. And it’s not just them. Whole generations are lost this way. How does one deal with that?”

That Van der Berg would lose sleep over the fate of marginalised youngsters in an impoverished region of South Africa, and try to do something about it, is typical of the engaged academic with a conscience that he is — someone who has “always found it difficult to be looking in from the outside”.

Over the past 15 years, his main vehicles for making a difference have been two intertwined entities, both based at SU: a national research chair and an influential research group.

The SARChI Chair

In 2008, Van der Berg was awarded the prestigious SARChI Chair in the Economics of Social Policy.

At the time, his successful proposal stated that South Africa had a dearth of quantitative educational research and research on the economics of education. As such, their goal with the Chair would be to concentrate on education, considering the urgent policy issues in this field, and to focus specifically on equity and educational outcomes in schools serving the poor.

In his final report, delivered when the Chair came to an end in 2022, he stated that it had achieved the following: stimulated high-quality social policy research (particularly empirical research in the economics of education), contributed to addressing social issues, developed and analysed new data sets, and influenced social and economic policymaking.

Building capacity through mentorship

Much can be said about each of these aspects, but when asked for his input, Dr Nic Spaull, a former student and colleague of Van der Berg, highlighted capacity building above all.

“Servaas’ biggest contribution is the group of people that he has mentored. If you look at how they are now scattered across the country and the rest of the world, and at the roles that they occupy, they are clearly having an incredible impact,” he says. Having completed both his master’s and doctoral degrees under Van der Berg’s supervision, Spaull has firsthand experience of his mentorship.

“Servaas has easily been the most influential mentor in my life,” Spaull says.

“I’m very grateful for his willingness to give his time and energy to some of us who had sharp edges that needed to be knocked off. He does that very graciously, with a kind of drip-feed treatment that gradually nurtures young researchers and helps them grow up.”

These sentiments are echoed by others.

“He’s been very generous with his time and resources,” says Nompumelelo Mohohlwane, a deputy director in the Department of Basic Education’s research, monitoring, and evaluation section. She is also a PhD student, co-supervised by Van der Berg.

“During the pandemic, he was very responsive and caring, always checking in with me and asking about my family,” she adds.

In the 15 years of Van der Berg’s Chair, 46 students that were either (co-)supervised by him or a member of his research group attained PhDs. A further 10, including Mohohlwane, are currently still under his supervision.

“This far exceeds our initial estimations of what would be possible,” Van der Berg writes in his final report.

Attracting students

As a professional scholar, Van der Berg views research as a powerful tool, yet he takes care not to neglect another important implement in the academic’s toolbox, namely teaching.

“For me, it has always been important to convey to students the type of things that I’m interested in and the conclusions we draw from our data analyses, thereby engendering a better understanding of the South African situation,” he says.

“As such, even when I was awarded the SARChI Chair, I didn’t want to reduce my teaching load. I particularly retained my third-year class because that’s where many of my postgraduate students come from.

“Those students who share my moral commitment to dealing with poverty and inequality are typically attracted to the work that the Chair does, and many of them end up doing their master’s or PhD with us. That’s very rewarding.”

A research group aimed at impact

The acronym stands for Research on Socioeconomic Policy, and the group comprises researchers and students interested in poverty, income distribution, social mobility, economic development, and social policy, including that around education, health, and labour issues.

“RESEP began when everyone realised that Servaas was a kind of grandfather or patriarch for a group of people working together that was very large but not formalised,” says Spaull, who moved to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in 2023.

He adds: “Working with Servaas is a very collaborative experience. He sets the tone very early on, namely that research is not about publishing in journals or climbing the ladder, but about impact. It’s about trying to shift outcomes for the worst-off in society, whether you’re dealing with poverty or education or health.

“He modelled that for us — how to do impactful work. I think that we underestimate the importance of that.”

What’s in a name?

“No,” Van der Berg says with a smile, “the acronym RESEP was not chosen as a nod to my wife.” Eunice, married to him more than 40 years now, is the daughter of SJA (Ina) de Villiers, author of the 1951 classic South African cookbook Kook en geniet (‘Cook and Enjoy’).

“The possibility that it might be interpreted that way did come up when I discussed the name with my colleague [Prof] Ronelle Burger but we decided to go with it in any case.”

‘RESEP’ (Afrikaans for ‘recipe’) nonetheless invokes the link between academic research and real-world impact. The group works on social policy matters needing attention to achieve improved outcomes, almost like the ingredients and method to be followed for cooking a dish successfully.

The economics of education

To fully appreciate the significance of Van der Berg’s contribution over the years, it is important to grasp that he has focused on education for most of his career, but as an economist, not an educator.

He chose to target education not only because it is an area in great need of improvement in South Africa but also because he considers it key to unlocking socioeconomic advancement for the population.

As a researcher in development economics and the economics of education, he uses analytical methods well established in the economic sciences – especially quantitative methods such as the statistical analysis of large data sets – to cast light on the challenges associated with policymaking in education.

According to Prof Abhijeet Singh of the Stockholm School of Economics, “the strength that economics brings to the study of education is the ability to use a fairly small set of unifying frameworks to think about different problems because the ability to bring rigour to how you treat data is a skill that cuts across sectors.”

Singh was a keynote speaker at the 2023 Quantitative Education Research (QER) conference in Stellenbosch, a popular event initiated by Van der Berg and hosted by RESEP each year. It routinely draws more than a hundred national and international participants, not just academics but policymakers alike.

Data wizardry

The strength that Van der Berg and his economics colleagues bring to the education table is the ability to work with data.

“Data is central to what we do in our research,” Van der Berg explains.

“In the past, very little data analysis was done in education [research] in South Africa. We try to overcome this by obtaining whatever data is available, analysing it, and placing it in the public domain in a way that is relatively user friendly and addresses policy needs at the same time.”

Van der Berg says he loves working with data, and his main focus is to get it to tell a story that will make a difference.

“I really like to create graphs, for instance, presenting them in a format that will hopefully affect people. If you can get the data to speak to policymakers, it can make a difference.

“Typically, we are able to extract more information from the system than that which officials are utilising. Administrative data is often not very good data. It contains a lot of ‘noise’, but we’ve become quite good at sorting it out and putting it to better use.

“There’s actually a wealth of information available, and if you link various indicators over time, you can identify schools and individuals that need interventions,” he says.

The cover of a journal featuring a working paper co-authored by Van der Berg, published in December 2023.

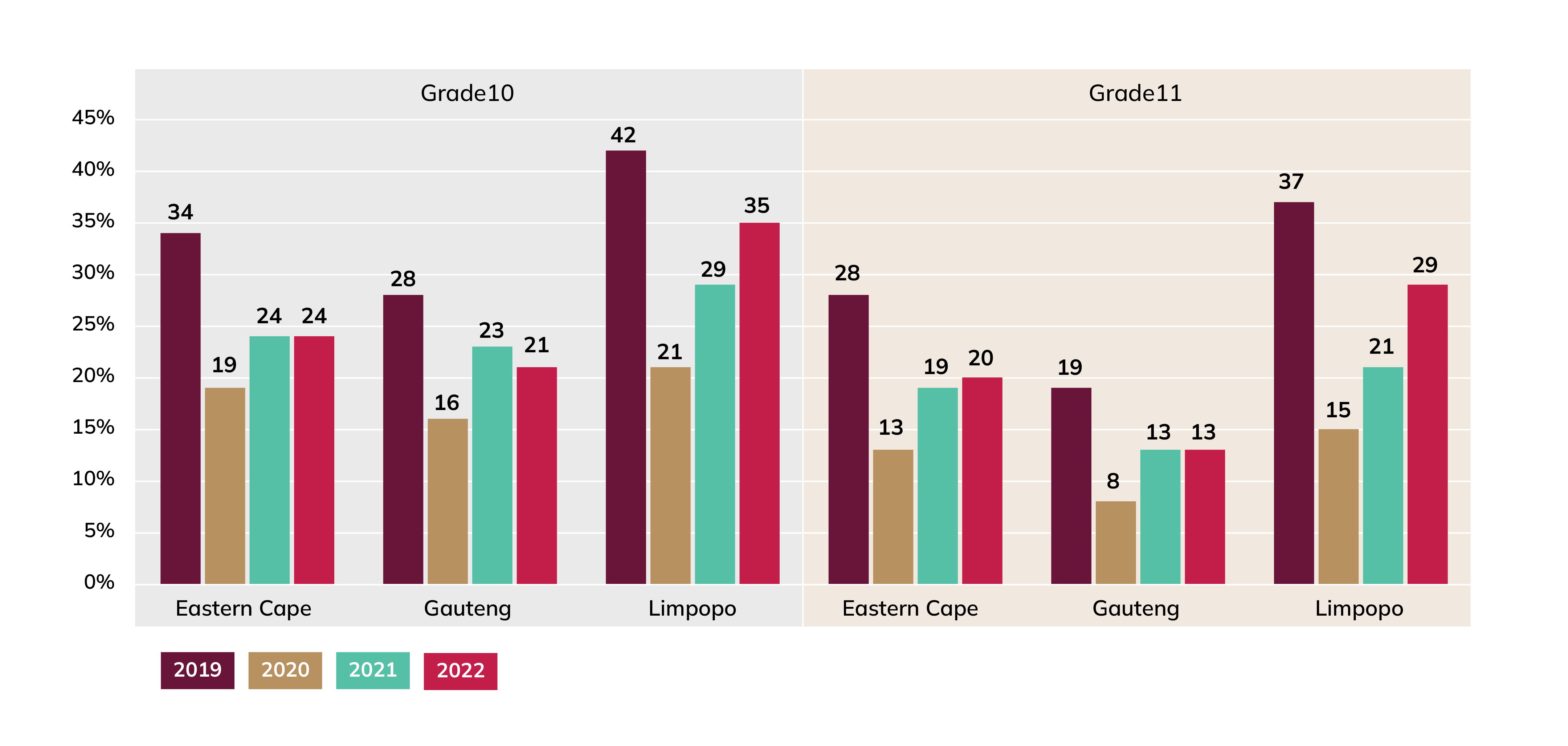

Repetition rates under the spotlight

RESEP has undertaken several studies about learner flows through school. Using data from the South African School Administration and Management System (SA-SAMS), the research group conducted the first in-depth analysis of how school-based assessments influence subsequent learner performance and predict grade repetition and dropout rates.

Their findings were alarming.

“South Africa has an extremely high repetition rate. Every year, around 1.1 million learners repeat a grade, which is almost 10% of the total number of learners in the school system. That’s massive compared to other countries, which points to substantial internal inefficiency in our system,” Van der Berg says.

At the same time, the report opened doors.

“We went on to co-host seminars and training workshops. Our analyses and advice on data issues were well received by large audiences and described as ‘tremendously useful’ by a senior official.”

Repetition rates, by year and province, for Grade 10 and Grade 11 South African learners: A graph from “What rich new education data can tell us”, a report authored by Van der Berg and colleagues.

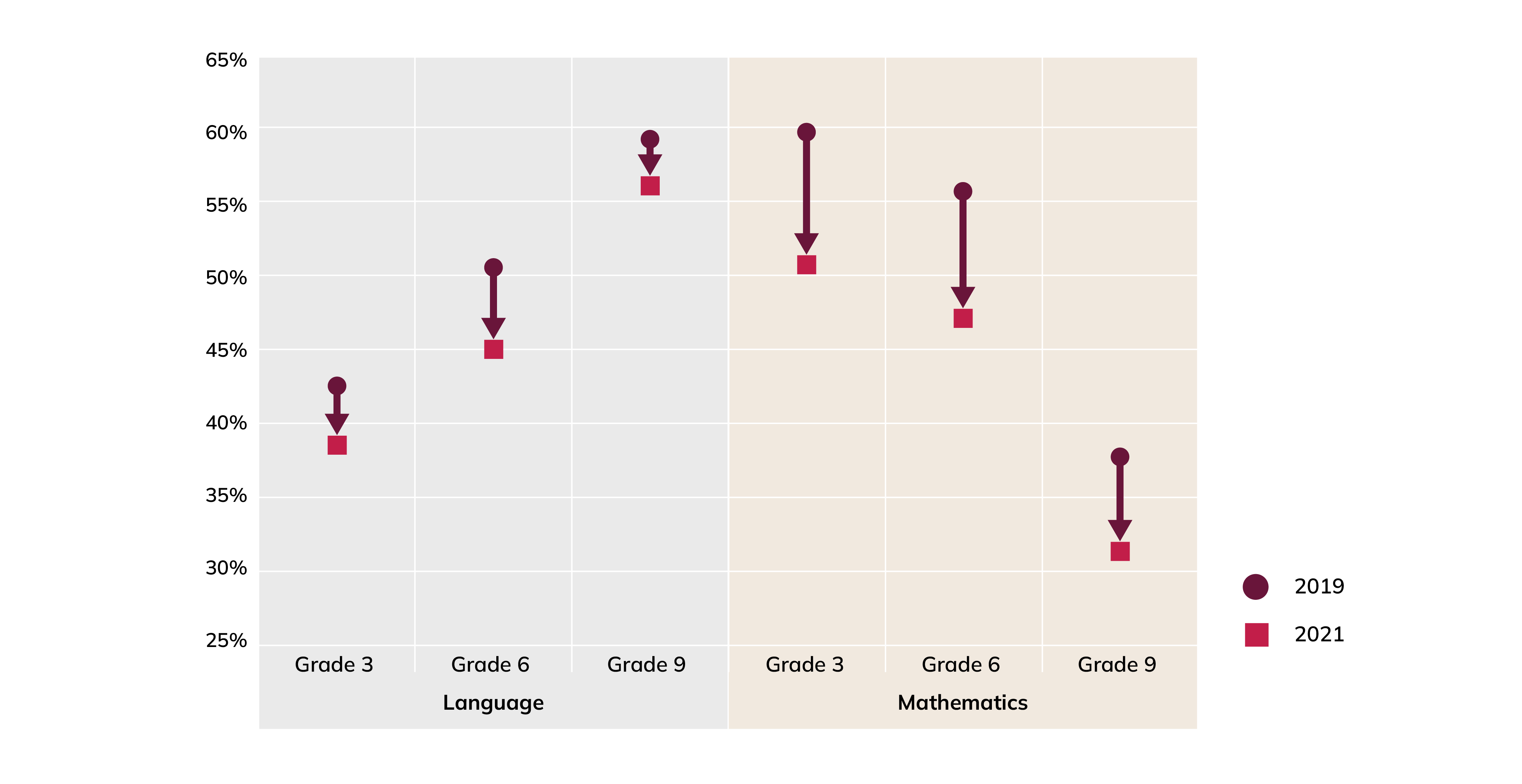

The impact of COVID-19

RESEP also reported worrying findings related to the considerable negative impact of the recent pandemic and its associated educational upheavals such as school closures and rotational timetables.

“Our analysis pointed to substantial learning losses: for mathematics, more than a year of learning and for reading, about two-thirds of a year. Moreover, we found that learning losses were significant even in more affluent schools,” Van der Berg says.

“These losses will affect learners for at least a decade and hold considerable implications for educational practice and policy.”

The cover of a journal featuring a working paper co-authored by Van der Berg, published in December 2023.

Van der Berg and his co-authors offered the first comprehensive picture of the long-term effects of the pandemic on learning outcomes across a whole province in South Africa, in both poor and rich schools. The results, published in the form of a report in February 2022, were extremely concerning.

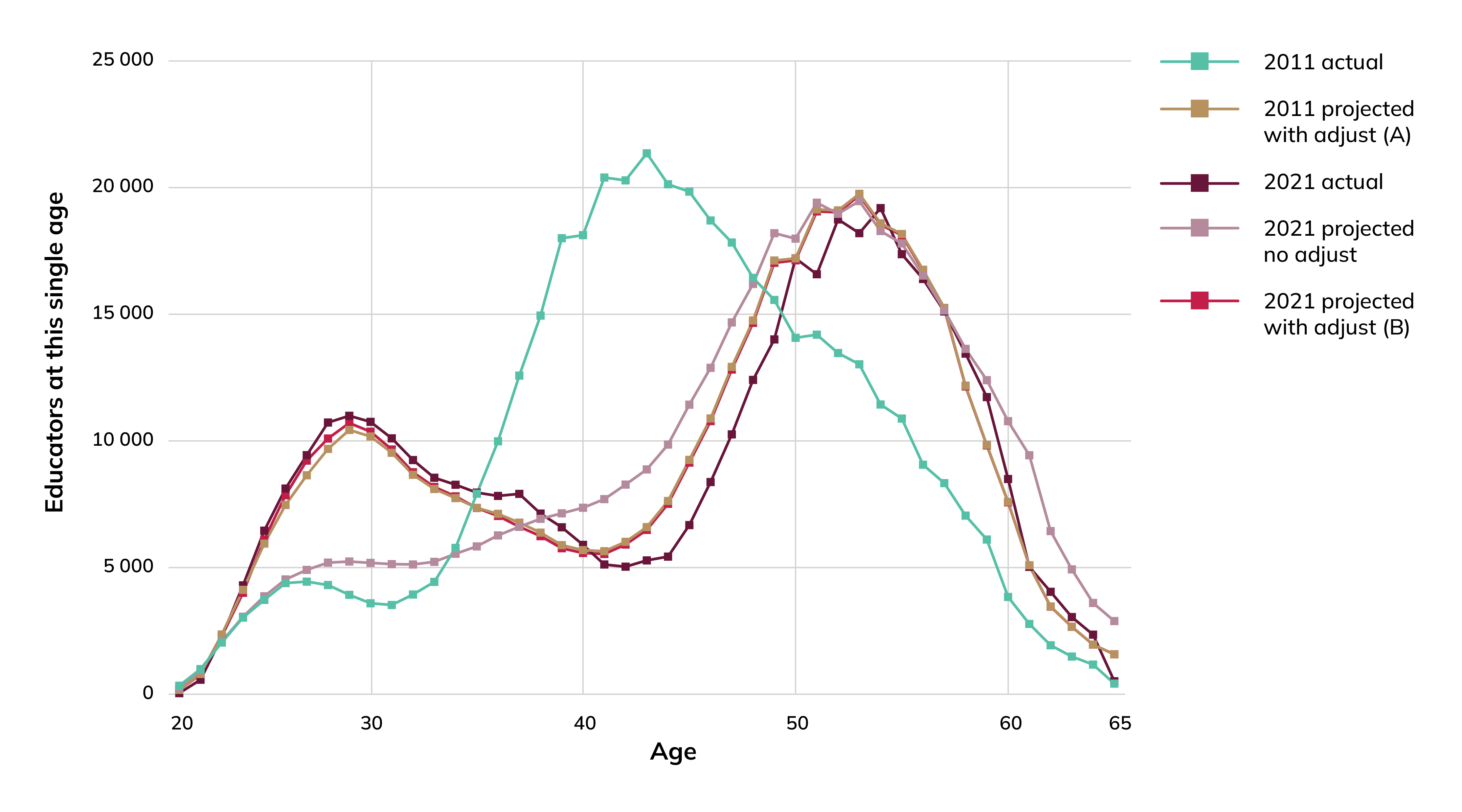

Supply of teachers

A final example of how Van der Berg and his colleagues make numbers tell a story is their study for the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) on the demand for and supply of teachers.

“We used a unique data set in that we matched matric examination data to Higher Education Management Information System (HEMIS) data and then to the government’s system for personnel and salaries (PERSAL), which contains teacher payroll data. This allowed us to track learners from school to university and into employment as teachers at public schools,” Van der Berg explains.

“The findings pointed to poor matric performance, high dropout rates at university, and a low number of appointments at public schools.

“In addition, many teachers will reach retirement age within the next 10 to 15 years, and the resulting shortage will likely present itself most strongly in rural areas. This places an enormous burden on the teacher training system.

“However, it also provides the DHET and universities with the opportunity to improve basic education because many teachers perform poorly and need to be better versed in the subject content they teach, which can be fixed with better teacher training.”

A graph from Projections of Educators by Age and Average Cost to 2070: A first report by Prof Martin Gustafsson, a colleague of Van der Berg, published in December 2022. By 2030, at least 19% of the existing workforce will have retired, as they were aged 56 or older in 2021 and will therefore be 65 or older come 2030. In 2035, this number will jump to 42%.

Qua vadis?

Van der Berg says there is too little funding available in South Africa to attract PhD students and postdoctoral fellows. That’s why he is appreciative of his SARChI Chair’s funding, which is harder to come by now that it has run its course.

Mary Metcalfe, a former head of the School of Education at the University of the Witwatersrand and current member of South Africa’s National Planning Commission, says: “In acknowledging the work of Servaas, we as a country also need to acknowledge the contribution of the SARChI Chairs. I hope the initiative continues for many years because, particularly in the field of public policy, we need to build new generations of young people with the skills to provide the rigour that is needed across government departments.”

Van der Berg has now formally retired but remains involved with RESEP.

“My own role might decrease and some of my colleagues will take over more of the responsibilities. But I have little fear about that, given the strength of the people involved,” he says.

A larger slice for everyone

Van der Berg has undoubtedly become synonymous with development economics in South Africa, particularly in the field of education.

His wish for the future is that “more learners get a quality education, which would help reduce poverty and enhance equality.”

If this vision is realised, the recipe that Van der Berg pioneered with his students and colleagues will contribute to making South Africa’s economic pie bigger, to the benefit of all.

The research initiatives reported on above are geared towards addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, and 10, and goals number 1, 2, and 18 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Useful links

SU’s Research on Socioeconomic Policy (RESEP) group

SARChI Chair in the Economics of Social Policy

X: @MatiesResearch and @StellenboschUni