The (sustainable) power of the public purse

Anél Lewis

Illustration by Roulé le Roux

Public procurement is big business. Globally, governments spend around USD13 trillion on the procurement of goods and services each year. In South Africa, this government expense amounts to almost R1 trillion annually — around 12% of the country’s annual gross domestic product (GDP).

According to Prof Geo Quinot of Stellenbosch University’s (SU’s) Department of Public Law, public procurement is the world’s single largest commercial activity: “The state is always the biggest market player.” He points out that the United States federal government is the world’s biggest consumer by far, with clothing, food, paper, and electronics topping the procurement list of consumer items in terms of both volume and value.

Public procurement is also responsible, be it directly or indirectly, for a significant portion (15%) of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to research by the World Economic Forum.

It is an area of public administration that is highly regulated. “Unlike you and I who can buy whatever and however we want, the state does not have that freedom. It is bound by legal rules around who buys what and how.”

As the director of the multi-institutional African Procurement Law Unit (housed at SU), Quinot focuses much of his efforts on promoting research on public procurement regulation on the continent.

Prof Geo Quinot of SU’s Department of Public Law | Photo by Stefan Els

The state as driver of sustainability

Whether it be for the purposes of constructing roads or power stations, purchasing office equipment, or securing trash-collection services, the efficient use of public resources contributes to better service delivery.

When public procurement laws are clear and enforced, they can help governments free up money and create jobs, support private businesses, and improve service delivery.

Moreover, the fact that public procurement occurs within a highly regulated environment presents an opportunity for it to be used as an instrument for realising sustainability as a policy objective, says Quinot. “When one starts looking at ways in which to change market behaviour on both the supply and demand sides toward a more sustainable approach, the intersection between the market and the state — as the biggest market player — becomes an important site of engagement.”

In an era defined by environmental degradation and climate change, the role of governments in promoting sustainability has become crucial. The sheer scale of government purchasing gives it the potential to shape markets, encourage responsible business practices, and drive sustainability across industries.

Governments could have a significant influence on industries that are heavily dependent on public spending. Public procurement activities produce seven times more greenhouse gas emissions than the entire global aviation industry. Up to 75% of these emissions stem from the activities of only six industries: defence and security, waste management services, transportation, construction, industrial products, and utilities.

To illustrate how a procurement decision can influence consumer behaviour, Quinot refers to the choice of many public authorities, worldwide and in South Africa, over the last few years to stop buying incandescent and regular fluorescent lightbulbs. Naturally, because of the higher price of more energy-efficient options such as light-emitting diode (LED) bulbs, there was initial resistance from consumers to do the same, says Quinot.

“But you get the state to say that they are committed to this, they see the long-term policy objective, and they are willing to pay for it.” The effect is that of changing the demand for alternative, greener options overnight. (Just imagine how many lightbulbs the total of a country’s government entities buy annually.) In turn, this impacts on both cost and the availability of these options to consumers at large. Eventually, they become the dominant options in the market, displacing the old, energy-inefficient ones. In this way, public procurement becomes one of a range of mechanisms that the government can use to realise its sustainability objectives.

Given that public procurement is so highly regulated, Quinot says, his interest lies in understanding how the law should be applied to make sustainability one of the policy objectives of public procurement. “So, how do we frame the rules in a way that’s going to support a sustainable approach to public procurement?”

The global north versus the global south

In a co-authored article on the concept and effects of sustainable public procurement, Quinot notes that sustainability has long been little more than a ‘buzz word’ or ‘fuzzy concept’ interpreted differently by various government agencies, political leaders, and interest groups.

It is only recently that environmental considerations have started to feature in public procurement objectives. This is more prominently the case in the northern hemisphere, particularly in Europe where the link between the environment and procurement is better established. In contrast, in sub-Saharan Africa the focus has been primarily on the link between procurement and social objectives such as wealth redistribution, opportunities for small businesses, gender equality, and job creation.

However, since the adoption of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by governments worldwide, there has been a noticeable shift towards a combined perspective. It’s no longer environmental or economic or social considerations that must be taken into account during procurement, but environmental and economic and social ones, says Quinot. “That is where we are now in terms of public procurement, and it’s exciting.

“The trick now is to try and balance these considerations so as to get to a point where we talk about sustainability as an objective as opposed to environmental, social, and economic objectives. They’re inextricably linked.”

Adding legitimacy to scholarly claims that sustainability is integral to public procurement is the inclusion of the latter in the foundations of the SDGs. Goal 12 focuses on ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns, and explicitly states that governments must support sustainable procurement policies.

“Governments need to implement and enforce policies and regulations that include measures such as setting targets for reducing waste generation, promoting circular economy practices, and supporting sustainable procurement policies.”

The SDGs have liberated public procurement from the Bretton Woods and Washington Consensus notions of trade as the only path to development, emphasises Quinot. Signed in 1944 to help countries recover economically from the Second World War, the Bretton Woods Agreement was intended to facilitate international trade and cooperation. The Washington Consensus, in turn, is a set of economic policy recommendations for developing countries that was popularised during the 1980s. A central tenet is that the operation of a free market and reduced state involvement are pivotal to development in the global south. In recent years, however, shifting priorities and changes in the global risks landscape have led to a worldwide consensus that a radical transformation in the shape of a new Bretton Woods Agreement is needed to address inequalities and place the needs of developing countries centre stage in global financial decisions.

This is not to say that the adoption of a novel approach to sustainable public procurement has been without its challenges. “When you bring policy into the mix, you must sacrifice some [level] of competition. The idea of public procurement for policy is often in conflict with competition. However, since the adoption of the SDGs, sustainability and not trade has become the holy grail of public procurement.”

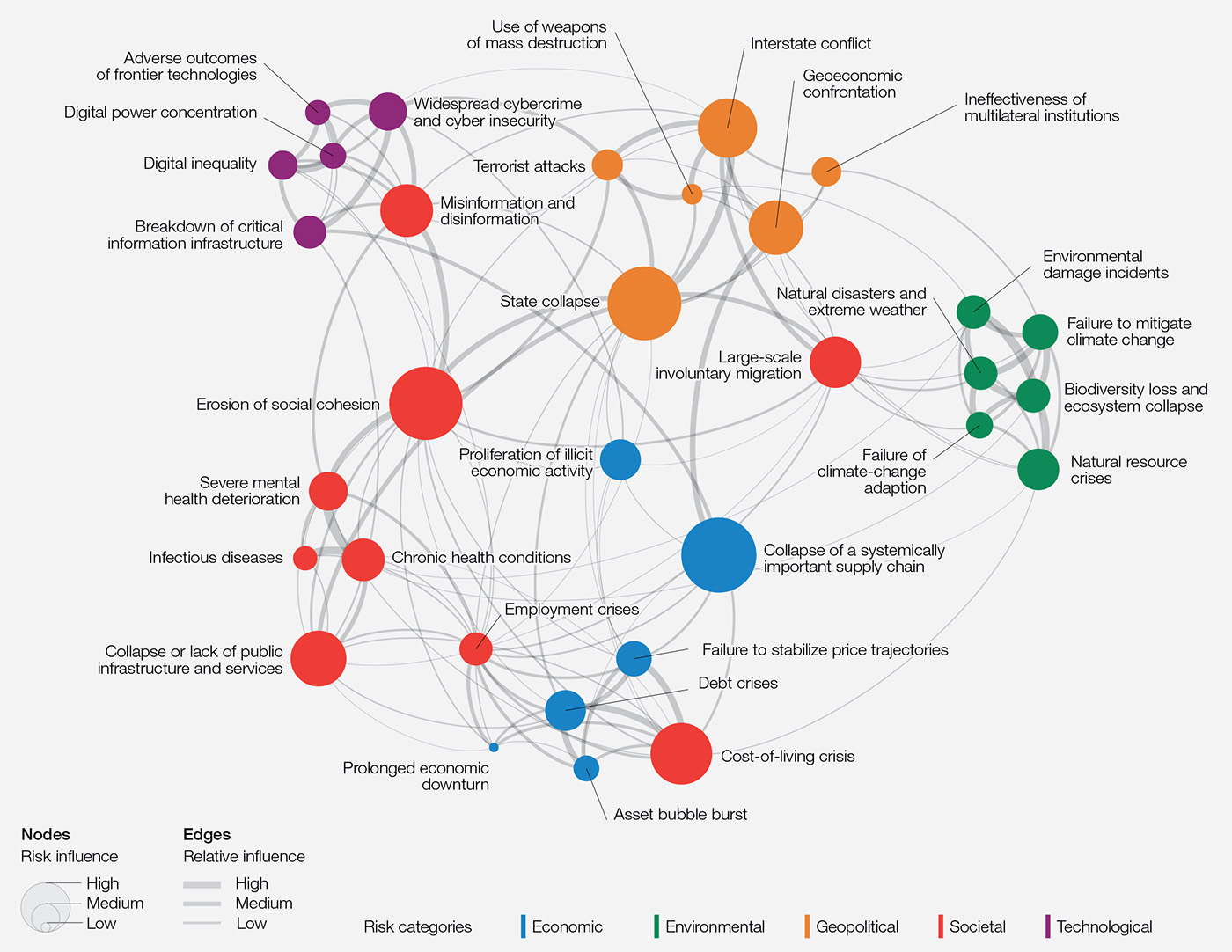

Global risks landscape: an interconnections map

The evolution of the global risks landscape, since the Bretton Woods Agreement, to include various risk categories. Source: World Economic Forum, Global Risks Perception Survey 2022–2023

Procurement by design

By far the biggest substantive point of contention in recent deliberations on South Africa’s new Public Procurement Act (No. 28 of 2024) has come from the chapter dealing with preferential procurement, Quinot says. “The debate across the political spectrum has been around how to build social policy — wealth redistribution — into public procurement. Some role players insisted that race should remain the criterion, while others supported class.” Moreover, the act does not deal with the pertinent question of whether there should be a preferential premium for this policy, he says. “How much more should you pay for an item if there is a social policy objective built in?”

These issues highlight the importance of designing laws that make it possible to include policy objectives into public procurement. “The design, for me, is the interesting part. How do you design a system that will deliver on this? It becomes interesting when you consider other mechanisms as procurement criteria, not just race or wealth redistribution,” says Quinot.

He adds that it’s important to consider the sub-Saharan African context when designing procurement systems, as “there are very important distinctions between our public administrations and those of Europe, for example”.

Although digital tools work well in supporting sustainable public procurement, many local municipalities simply do not have access to these resources. In places that don’t even have a reliable electricity supply, it is unrealistic to expect smaller players to upload large tender documents onto a platform that may or may not work on any given day, Quinot argues. “We simply don’t have the digital depth that many other systems do.” While there are certainly practices that work elsewhere, one must always ask whether they translate into the local reality.

Food for thought

To illustrate how sustainability can be incorporated into public procurement, Quinot references his work with the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) on public food procurement for school feeding schemes. Regarding the FAO’s pilot projects, Quinot says: “It is astounding to see how you can connect dots across many different fields. In Ethiopia, for example, they have shown how various government departments — including education, health, and agriculture — as well as local subsistence farmers and small businesses can work together. So, you are rewarded with not only the substantive outcomes on half a dozen different policy objectives, but the way in which the procurement process works is also sustainable.”

As an added bonus, this approach also indirectly reduces the risk of the procurement process being abused, he adds. “Now, when the children show up at school and there isn’t a meal, it’s not a matter of a bad contractor somewhere not doing their bit. It’s the mothers and fathers of that very community. So, that farmer or the small business preparing the food internalises the cost of non-performance.” He goes on to explain: “If it’s my own child I’m feeding, and I’m known in the community, why would I be corrupt?” Quinot describes this kind of alignment between the regulatory instrument and the objective, with a built-in mechanism to minimise corruption, as “a thing of beauty”.

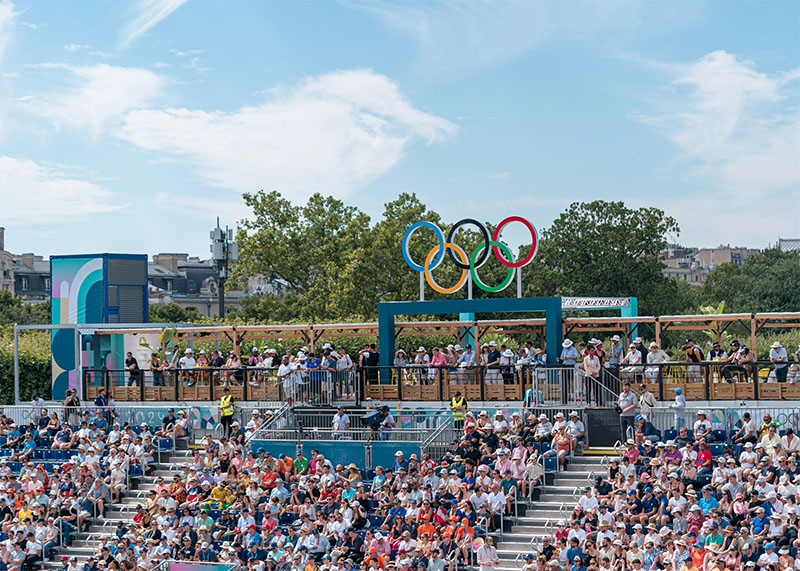

The recent Olympic and Paralympic Games in Paris present an example of how a responsible procurement strategy can help make large events more sustainable.

On your marks

This year’s Olympic and Paralympic Games in Paris present a good example of how a responsible procurement strategy can help make large events more sustainable. With the aim to reduce their carbon footprint by 55% compared to the 2012 London games, and to be the first international sporting events to achieve carbon neutrality, the Paris games adopted a comprehensive purchasing strategy. The latter saw all procurement contracts structured around a commitment to five actions that drive environmental and social innovation, namely: supporting the circular economy, reducing the events’ carbon footprint, preserving the environment, including persons with disabilities, and creating value in local areas by encouraging small and large businesses to join forces in consortiums.

One of the ways in which the events reduced their negative environmental impact was by prioritising renovation over new construction — 95% of the buildings in the Olympic Village were existing, repurposed ones.

As part of the commitment to socially responsible procurement, the authorities organising the events included a clause in tenders that encouraged the promotion of opportunities for social, as well as small and medium-sized enterprises. Although many of the socially responsible, green, and circular economy public procurement targets were met, a recent report by RREUSE states that there are still barriers to leveraging public procurement for environmental, climate, and social benefits. More than half of all public tenders in the European Union still use lowest price as the only selection criterion.

Greening healthcare

Closer to home, the George Regional Hospital in the Southern Cape recently incorporated environmental objectives into its procurement processes. This hospital is one of three institutions nationally that were identified to pilot the Global Green and Healthy Hospitals carbon footprint tool, designed by the organisation Health Care Without Harm. This tool made it possible for the hospital to measure its carbon footprint across its supply chain. Procurement officials launched the process by discussing sustainable procurement strategies, policies, and plans with their teams. Other actions included considering which sustainability concerns were a priority for upcoming tenders, revising standard operating procedures, and engaging with suppliers on the topic of sustainable procurement.

The case study revealed some of the challenges that the healthcare facility faced. For example, suppliers were hesitant to get involved in the project and many assumed more sustainable options would not be cost effective. But there were also many positive outcomes, including the identification of 14 green suppliers with 100% recyclable packaging and a reduced use of harmful chemicals.

The future of public spending in South Africa

The Public Procurement Act (No. 28 of 2024) standardises procurement practices across all organs of state. This new legislation explicitly states that it will “promote innovation, sustainable development, and the environmental rights in section 24 of the Constitution”.

This legislation’s explicit mandate for the pursuit of sustainable public procurement is meaningful, says Quinot. “Internationally, research has shown that the presence or absence of an explicit legislative mandate for sustainability is a major factor in the uptake of sustainable public procurement.”

For example, UNEP’s Sustainable Public Procurement 2022 Global Review (the most comprehensive study on the state of play in sustainable public procurement globally) reports that policy commitments, goals, and action plans, as well as mandatory sustainable procurement rules or legislation are the top drivers of sustainable public procurement among the countries surveyed. Conversely, a lack of mandatory sustainable procurement rules or legislation was cited as the second biggest barrier to the implementation of sustainable public procurement.

“It follows that the inclusion of sustainability in our new legislation is a critical first step toward greater inclusion of sustainability considerations in our public procurement practices,” Quiniot says. He adds that the next step is to define regulations under the new act that will give it substance.

The act also aims to address the widespread corruption in public procurement, as highlighted in the findings of the Zondo Commission of Inquiry into allegations of state capture. The act sets up a public procurement office under the National Treasury that can issue binding instructions to all organs of state, excluding municipalities.

Although the new act is but one part of the bigger sustainable public procurement picture, it is a useful tool in ensuring a connection between policy decisions and outcomes, concludes Quinot.

The power of the public purse

- Every year, public procurement constitutes roughly 15% of the world’s GDP.

- Public procurement has long been considered a key instrument of development in sub-Saharan Africa, and used to promote socioeconomic policies.

- Government procurement in South Africa is big business — the government spends close to R1,5 trillion a year on goods, services, and construction.

Sources: The World Economic Forum and the World Bank

The green opportunity

- Be it directly or indirectly, public procurement activities are responsible for 15% of all greenhouse gas emissions globally, which is seven times the amount emitted by the entire global aviation industry.

- In addition to ensuring far lower emissions, climate-sensitive public procurement procedures will stimulate the green economy, reduce the social cost of carbon, and lead entire industries toward a net-zero future.

- Through its large scale and high level of spending, public procurement has the potential to positively impact global efforts to slow climate change and reduce pressure on natural resources and ecosystems.

- In total, efforts by the world’s governments to reach net-zero emissions will increase procurement costs by 3–6%.

- However, unless we can slow global warming, public procurement costs will skyrocket as governments spend to adapt to the effects of climate change.

Sources: The World Economic Forum, ICLEI, and the World Bank

The research initiatives reported on above are geared towards addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals numbers 3, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 16, and goals number 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 11 and 12 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Useful links

The African Procurement Law Unit (APLU)

What is the circular economy and why does it matter?

Public procurement is a powerful tool for sustainable development — UN report

The future of public spending: Why the way we spend is critical to the Sustainable Development Goals

New public procurement law aims to put money where it is most needed

2024 APLU public procurement reform workshop

X (formerly Twitter): @MatiesResearch and @StellenboschUni