Transdisciplinary research aims to dish up food security

Ufrieda Ho

It doesn’t add up — on the one hand, we have established food production and supply chains and massive food surpluses; on the other, we have pervasive hunger and growing levels of malnutrition affecting more and more South African households.

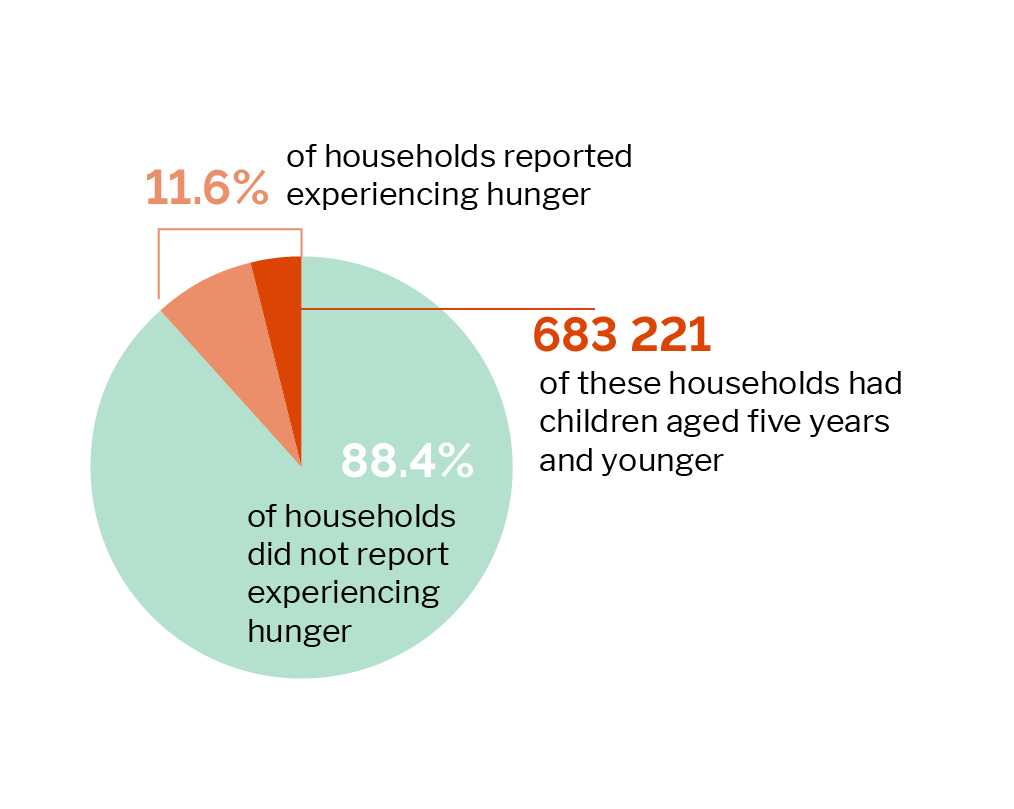

According to the 2022 national census and StatsSA’s analysis, 2.1 million (11.6% of) South African households reported experiencing hunger in 2021. This statistic has spurred researchers at Stellenbosch University (SU) to expand their approach to levelling this imbalance. Their subsequent work forms part of initiatives aimed at building stronger food systems that incorporate good nutrition, improve food security, and consider sustainability in a time of climate change.

Their emphasis is on ensuring that food systems are viewed through the lens of the intersecting challenges of health service delivery, adequate water and sanitation services, poverty, and entrenched inequalities.

Transdisciplinary research has seen SU’s scientists come together in a public square initiative to focus on a systems-based approach to tackling malnutrition. This approach allows for consideration of the multiple drivers of malnutrition in society, and for roleplayers to respond with greater urgency in order to limit the long-term burdens of this condition. Importantly, the approach is deliberate in driving collaborative solution-finding.

The SU researchers in this square are drawn from different departments and faculties, and also work with partners in NGOs, other universities, municipalities, and within communities.

An estimated 5.7 per cent or 38.9 million children under 5 around the world were affected by overweight in 2020.

In 2020, wasting continued to threaten the lives of an estimated 6.7 per cent or 45.4 million children under 5 globally.

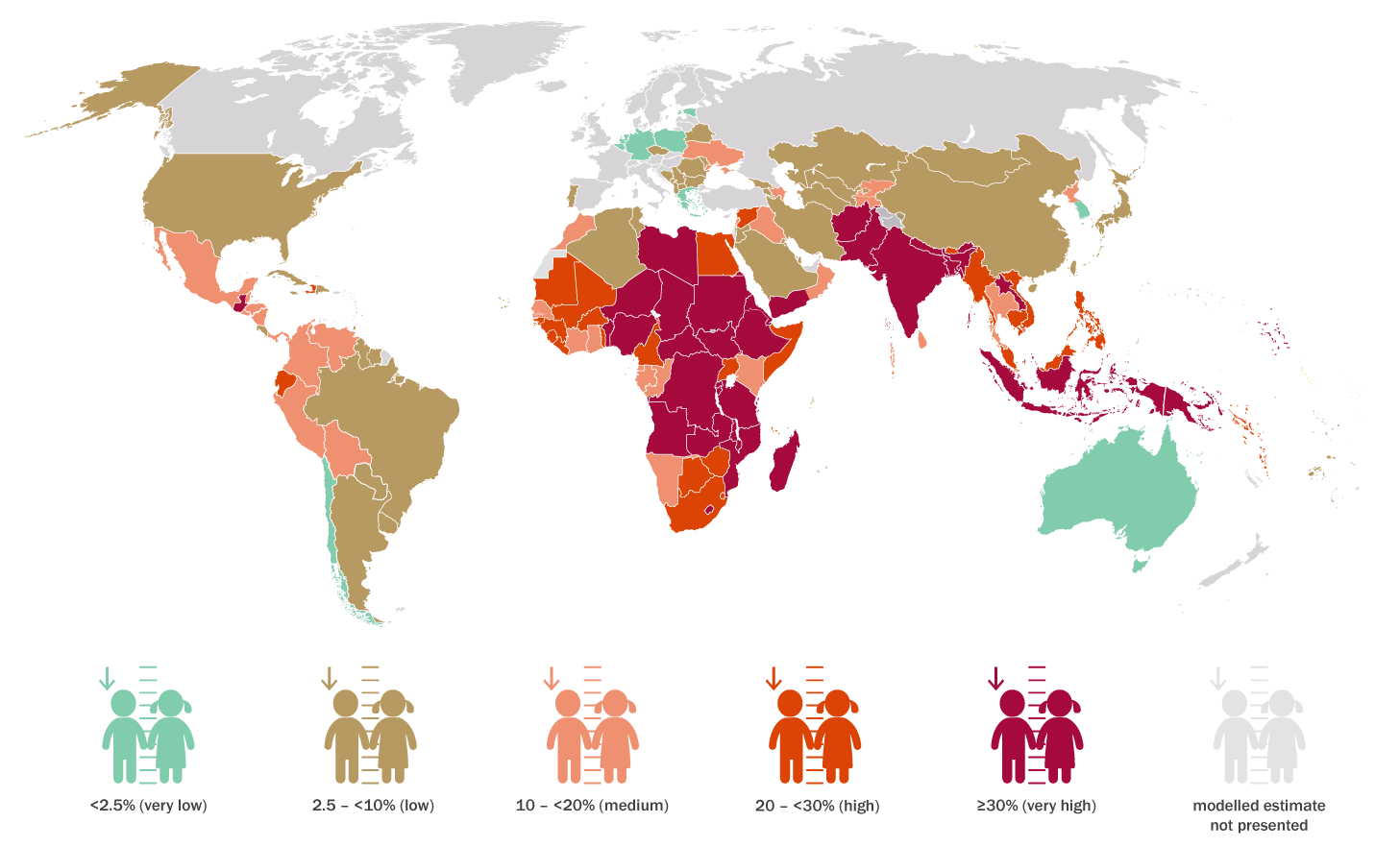

Stunting affected an estimated 22.0 per cent or 149.2 million children under 5 globally in 2020.

Most children with malnutrition lives in Africa and Asia

In 2020, more than half of all children under 5 affected by stunting lived in Asia and two out of five lived in Africa.

In 2020, more than two thirds of all children under 5 affected by wasting lived in Asia and more than one quarter lived in Africa.

In 2020, almost half of all children under 5 affected by overweight lived in Asia and more than one quarter lived in Africa.

Forms of malnutrition

Stunting

Refers to a child who is too short for his or her age. Children affected by stunting can suffer severe irreversible physical and cognitive damage that accompanies stunted growth. The devastating consequences of stunting can last a lifetime and even affect the next generation.

Wasting

Refers to a child who is too thin for his or her height. Wasting is the result of recent rapid weight loss or the failure to gain weight. A child who is moderately or severely wasted has an increased risk of death, but treatment is possible.

Overweight

Refers to a child who is too heavy for his or her height. This form of malnutrition results when energy intakes from food and beverages exceed children’s energy requirements. Overweight increases the risk of diet-related noncommunicable diseases later in life.

Source: UNICEF/World Health Organization/World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates Group 2021 (infographic adapted)

Food security stats serve SA an empty plate

Prof Scott Drimie of the Division of Human Nutrition in SU’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences is also the director of the Southern Africa Food Lab, co-hosted by the University. Drimie summarises the dilemma: “The issue here is that this [food security challenge] is not a linear problem that an economist or a nutritionist can solve on their own. Look at the problem of stunting, for instance: on one level it’s about food, but on others it’s about care, sanitation, hygiene, and the health system. We need to have all of these things in the same place at the same time, for the same child.”

Building a clearer, more nuanced understanding is critical, Drimie argues. “It is an indictment [of South Africa’s commitment to establishing food security] that we don’t have more platforms in the country that encourage collective, broad approaches,” he says. “We need more innovation and solutions emerging from sustained dialogue and a commitment to action — whether it’s through policy, shortening value chains, incorporating indigenous food systems, or any of a range of other possibilities.”

Ultimately, Drimie says, the alarm bells should have already rung as the looming crises are damning. Statistics from the Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa show that 28% of children in the country are afflicted by stunting, a situation which has worsened over the past 30 years.

Children who suffer from stunting do not timeously reach standard height milestones. According to the World Health Organization, this puts them at risk of developing chronic diseases, weakened immune systems, impaired cognitive abilities, high blood pressure, and obesity.

Despite important nutrition-related policy and programme improvements in South Africa, the rates of stunting among the country’s young children remain unacceptably high — much higher than in several other low- and middle-income nations.

But stunting is not the only condition that points to a larger nutrition crisis. Drimie explains that there are rising numbers of children presenting as underweight or suffering from severe acute malnutrition (marked by a very low weight-for-height, bilateral pitting oedema, or a very low mid-upper arm circumference). “In all of these [malnutrition] conditions, physiological growth is impacted and so are brain function and brain development. In cases of severe acute malnutrition, it can lead to death.

“On the opposite end, the nutrition challenge is that we see high rates of people who are overweight or obese.” Right now, 50% of adults in South Africa — more than the percentage two decades ago — fall into this category. Compared to other low- and middle-income nations, South Africa’s progress in addressing these issues falls short.

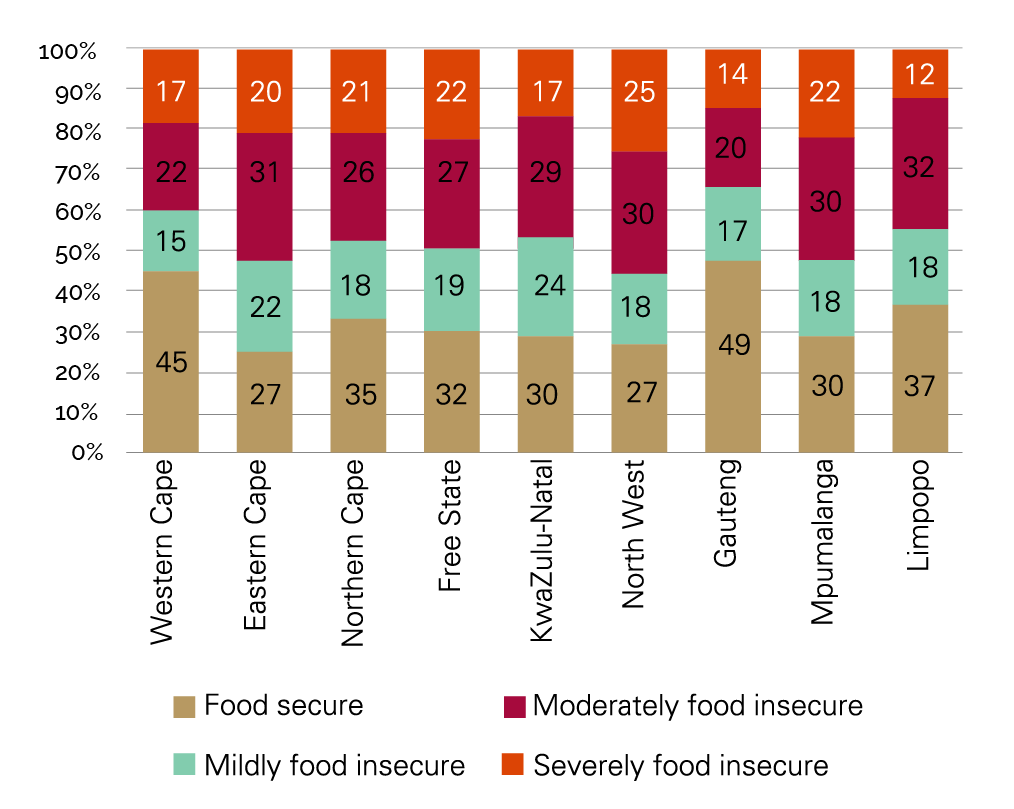

Food security status disaggregated by provinces in South Africa

Food security status disaggregated by provinces in South Africa. | Source: HSRC Review

Households that reported experiencing hunger in South Africa in 2021

South Africa has enough food and numerous food programmes, yet millions of people still go to bed hungry. | Source: Statistics South Africa

The number of countries with very high stunting prevalence has declined by half since 2000 – from 67 to 33 countries.

Percentage of children under 5 affected by stunting, by country, 2020*

*Distribution of stunting prevalence for each country with a modelled estimate presented for 2020.

Source: UNICEF/World Health Organization/World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates Group 2021 (infographic adapted)

The doom of the modern diet

Modern diets and food systems have undergone a rapid, drastic transformation in the past 50 years. Joelaine Chetty, a PhD student in the Division of Human Nutrition and a research dietician in the South African Medical Research Council’s Biostatistics Unit, is connecting the dots. She points out that the deterioration of our nutrition system over the past five decades can be attributed to two factors: the industrialisation of food production and the accelerating impact of climate change.

“The highly processed energy-dense foods we have now are often low in essential nutrients and high in sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats. This shift in dietary patterns contributes to the global rise in obesity and diet-related diseases, while exacerbating malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies,” she explains.

But that’s not all: The unfolding climate crisis is adding food production and security pressures to the mix. Chetty says: “The increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events such as droughts, floods, and storms are disrupting and having adverse effects on food production. This, in turn, affects crop yields, livestock production, and distribution networks, leading to food shortages and price volatility.”

Chetty believes, however, that reversing this trend is possible through interventions such as localising and diversifying food systems. She says:

“We have the potential to foster local food production, distribution, and consumption, thereby reducing our reliance on imported goods and strengthening community resilience. By supporting small-scale farmers, local markets, and food sovereignty initiatives, we can significantly enhance food security and economic stability at the grassroots level.

“Promoting agricultural diversification reduces the reliance on a limited number of crops or livestock breeds. Diverse farming systems build resilience against climate variability, pests, and diseases, and can buffer against crop failures and market fluctuations.”

Chetty believes investment in research, innovation, and technology transfer is also crucial to protecting our nutrition system from further deterioration. This involves paying more attention to resilient crop varieties, adapting and improving agricultural practices, and supporting small-scale farmers.

Moreover, Chetty argues, there is a need for what she calls ‘nutrition-specific interventions’ — efforts that not only ensure access to food but also promote diverse, nutritious diets. These interventions include micronutrient supplementation, improving nutrition education, promoting breastfeeding, and strengthening dietary guidelines that encourage the consumption of fruits and vegetables, specifically indigenous vegetables.

Chetty underscores that addressing food security is a collective responsibility that requires coordinated efforts across sectors and stakeholders. She advocates for public-private partnerships and better civil society engagement, as these are essential for mobilising resources, sharing knowledge, and implementing effective solutions at scale.

In South Africa, 10 million tonnes of food go to waste every year. This accounts for a third of the 31 million tonnes that are produced annually in the country.

Together, fruits, vegetables, and cereals account for 70% of food wastage and loss, which mostly occur early in the food supply chain.

Modern diets and food systems have undergone a rapid, drastic transformation in the past 50 years. The highly processed energy-dense foods we have now are often low in essential nutrients and high in sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats.

Giving back indigenous foods their seat at the table

Prof Xikombiso Mbhenyane, head of the Division of Human Nutrition, is a dietician with a particular interest in indigenous food systems. She is also the faculty’s DSI-NRF Research Chair in Food Environments, Nutrition, and Health.

Indigenous food systems, she says, have been excluded from mainstream ones and left to linger on the margins in terms of production, access to markets, and investment. Integrating indigenous foods into the broader markets, however, can strengthen local food systems, she believes.

That said, the challenges in the promotion, production, accessibility, and consumption of indigenous foods are plenty. For instance, Mbhenyane says, the availability and accessibility of indigenous foods still vary widely from province to province, and between the formal and informal markets. Without more consistent, reliable supply chains, consumers are less inclined to normalise indigenous foods into their everyday diets. Additionally, Mbhenyane says, our current food systems — which are failing — will remain unchanged without targeted support for small-scale farmers who grow indigenous crops, or for those who harvest from the wild.

“For indigenous foods to be promoted for cultivation and consumption, we need protection and accessibility in the market,” she says. Land management must balance the importance of land for growth (through commercial or housing developments) with land for food security (through agriculture), Mbhenyane adds.

She also makes the case for subsistence farming and the promotion of urban food gardening. Growing your own food not only supplements your household food supply, she says, it also saves money, restores people’s connection to how food comes to a table, and recovers the forgotten benefits of indigenous foods.

An urban farmer herself, Mbhenyane names two of her favourite indigenous foods of which the nutritional value is often overlooked, and which she believes should be part of our diets: Amaranthus cabbage (Amaranthus thunberghi) and cowpeas (Vigna unguiculata). The first is a semi-wild species of amaranth that grows in southern Africa. Mbhenyane says the plant is rich in micronutrients and can be used in the same way as garlic to flavour dishes. Cowpeas, also called ‘black-eyed peas’, is a versatile, resilient crop harvested for its seeds, pods, and leaves. Apart from being eaten by humans, it is also used in animal feed.

“We also often hear from the older people that cowpeas are eaten as part of a diet that helps to control diabetes, so this is an area of new studies,” Mbhenyane says. More research into indigenous food systems can unlock traditional knowledge, she says, and ensures its preservation in repositories.

Prof Xikombiso Mbhenyane | Photo by Nardus Engelbrecht

Prof Scott Drimie | Photo by Stefan Els

New perspectives, new solutions

Prof Sara Grobbelaar from the Department of Industrial Engineering has put engineering innovation at the heart of solving problems in our food systems. Her research interests include mitigating the severe consequences of wealth and income disparities.

Grobbelaar says: “Industrial engineers take a systems approach [to problem solving], and a systems perspective is particularly valuable when considering problems that have interconnected elements. As we aim to understand the wicked [i.e., interconnected and therefore seemingly insolvable] problems of the world, like those of hunger or growing food insecurity, we see that we can contribute to finding more effective and sustainable solutions.”

She homes in on the issues of food waste and hunger, which are at the opposite ends of the same food chain. According to the United Nations Environmental Programme, about a third of all food produced globally goes to waste — this translates to 3 billion tonnes of food a year ending up in the bin. At the same time, statistics show that 8 billion people worldwide suffer from food insecurity and as many as 750 million of these people are unsure, on a day-to-day basis, of whether or not they will have a meal.

“This disparity highlights a significant disconnect between food supply sources and demand areas, indicating poor management of food resources. This means issues around food waste can be approached by examining the entire value chain — from demand and distribution to production.

“Some of our [research team’s] work considers how we can help integrate circular economy principles into wholesale food markets to improve efficiency throughout the supply chain. Another project looked at food banks and how we can help them donate food to vulnerable people in the most efficient way,” Grobbelaar says.

She and her team recently collaborated with FoodForward SA. This food bank is the largest on the continent and distributes around 950 000 meals daily in South Africa through its network of beneficiary organisations.

Grobbelaar says: “This collaboration sparked our interest in growth stunting. It led us to work with a group of experts in fields that were new to us and, in turn, we could introduce them to experts we worked with on other projects. This created a virtuous loop of collaboration.”

Their ongoing work with FoodForward SA has seen the research team assess the day-to-day operations of the food bank to create a scientific basis for measuring and reporting on the social, economic, and environmental impacts of the charity’s work.

They have also analysed these findings with the objective of reducing the organisation’s carbon footprint and other pollutant emissions. Already they have inadvertently come up with an innovative strategy that will potentially bolster operational income for the non-profit. Their model lays out possible new avenues of income generation for the food bank through measures such as trading carbon credits, while streamlining operations to be more energy efficient and to reach more hungry people.

Another successful project by Grobbelaar’s research team was undertaken in collaboration with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Together, the cross-continent teams worked on developing a system dynamics model to assess food supply chains in wholesale markets in Mercabarna in Barcelona, Spain.

“This project highlighted the importance of having proactive infrastructure investment, ensuring adequate capacity and cold storage, and forming strategic alliances with food banks and charities to repurpose potentially wasted food.

“We were also able to introduce processing capabilities to extend food shelf life by turning fresh vegetables into soups and vegetable pulp,” Grobbelaar says. She believes the success of the project lay in the deliberate bringing together of many different intermediaries.

Grobbelaar is under no illusion, however, that there aren’t major blockages in food systems, especially when it comes to implementation, and finding ways to ensure continuity, adaptability, and sustainability.

“Systems thinking and system dynamics modelling are proving useful in strengthening food systems. However, implementing these practices in the real world is complex and often beyond the control of any single individual or group,” she says.

This does not mean we have the luxury of being discouraged, she says, as the stakes are simply too high. UNICEF estimates that the costs of undernutrition in Africa and Asia are equivalent to losing 8 to 11 percent of GDP every year, while investments in nutrition offer a $16 return for every $1 invested.

“If we don’t have enough coordinated intervention to tackle the mounting crisis, the consequences will be dire. The developmental, economic, and social impacts of malnutrition, especially in the early years of life, are serious and long-lasting for individuals, their families, communities, and countries.

“I’m optimistic, though, that we are beginning to see more transdisciplinary collaboration. We need to overcome the challenge of not seeing the potential in disciplines beyond our own.

“Other experts bring their unique perspectives and when we are able to harness and harmonise them with ours, then we have what it takes to move forward in the right direction,” Grobbelaar says.

Prof Sara Grobbelaar | Photo by Stefan Els

Malnutrition — food for thought

- In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that, across the globe, 128.1 million children under the age of five years were suffering from stunting, 45 million were suffering from wasting, and 27 million were overweight.

- Acute malnutrition in South Africa, including moderate and severe forms, is a significant underlying cause of child mortality. UNICEF says one-third of all child in-hospital deaths in the country are attributed to acute malnutrition.

- South Africa is expected to have 1.7 million stunted children in 2025 — nearly twice as many as the target of 900 000 children for that year.

- Stunting affects more boys than girls and is irreversible. It can have short- and long-term consequences, including developmental delays, poor cognitive function, and an increased risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease.

- Stunted adults often exhibit reduced economic productivity, which can perpetuate the cycle of poverty and malnutrition.

- Every year, over 15 000 children are diagnosed with severe acute malnutrition in South Africa, with 1 000 dying as a direct cause of it.

- The underlying drivers of malnutrition identified by UNICEF and the WHO are linked to severe poverty as it limits people’s access to nutritious food, clean water, and decent healthcare.

- Nutritional well-being is particularly vital during the first 1 000 days of life, starting from conception to around two years, thereby placing an equal focus on maternal health. The WHO puts South Africa’s breastfeeding rate at 32%, compared to the organisation’s target of 50% for 2025.

- According to the 2023 Global Hunger Index, sub-Saharan countries achieved considerable progress in reducing hunger between the years 2000 and 2015. The scores for 2015 to 2023, however, indicate that “progress has nearly halted”. This index found that the proportion of undernourished people in Africa rose from 14.9% in 2010–2012 to 19.3% in 2020–2022.

- South Africa is experiencing a severe food crisis, both in terms of affordability and availability.

- In some parts of South Africa, there are people who still go to bed hungry or eat only once or twice a day.

- Although food inflation has now eased to 12% and South Africa is food secure at the national level, many families still struggle to afford (especially nutritious) food.

Sources: Global Nutrition Report, World Health Organization, the Global Hunger Index, UNICEF and the DG Murray Trust

Food waste

- Worldwide, 783 million people are hungry and a third of humanity faces food insecurity.

- Even so, in 2022, the world wasted 1.05 billion tonnes of food. Most of this type of waste (60%) came from households.

- On average, each person wastes 79 kg of food annually. This is the equivalent of 1.3 meals every day for a year for everyone in the world impacted by hunger.

- Food waste is not just a ‘rich country’ problem. High-income, upper-middle income, and lower-middle income countries differ in observed average levels of household food waste by just 7 kg per capita per year.

- In South Africa, 10 million tonnes of food go to waste every year. This accounts for a third of the 31 million tonnes that are produced annually in the country.

- Together, fruits, vegetables, and cereals account for 70% of the aforementioned wastage and loss, which mostly occur early in the food supply chain.

- Food loss and food waste are responsible for up to 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions — almost five times the total emissions from the aviation sector.

Source: UNEP's Food Waste Index Report 2024 and WWF-SA

Food insecurity and malnutrition

- Food insecurity and malnutrition in Southern Africa is deeply concerning when compared to the global average.

- More than a quarter of South Africa’s children have a deep, chronic lack of protein that undermines their potential.

- The National Health and Nutrition Survey shows a 13% obesity rate among children aged one to five — twice the global average of 6.1%.

- Over 13 million children in South Africa receive the government’s child support grant. There is a 33% shortfall between the cost of the food children need to grow well and what their parents can afford to buy with the monthly grant.

Source: DG Murray Trust

The research initiatives reported on above are geared towards addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals numbers 2, 3, 9, 10, and 12, and goals number 1, 3, 5, 7 and 13 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Useful links

SU’s Division of Human Nutrition

SU’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences

The South African Medical Research Council’s Biostatistics Unit

SU’s Department of Industrial Engineering

The United Nations’ State of Food and Nutrition Security in the World report

The United Nations’ Environment Programme’s Food Waste Index report

Global Report on Food Crises 2024

South Africa’s children are dying of hunger

Poor South African households can’t afford nutritious food — What can be done

WWF-SA's Food Loss and Waste: Facts and Futures report

Prof Sara Grobbelaar’s inaugural lecture