PTSD: The body remembers

Engela Duvenage

Illustration by Ronel van Heerden

The lasting effect of a traumatic ordeal not only plays mind games with people who subsequently develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) — a trauma-induced, often debilitating mental disorder that counts prolonged flashbacks, nightmares, and severe panic attacks among its many symptoms.

It also leaves physical ‘fingerprints’ in the body that can be so permanent that it predisposes the individual to chronic metabolic diseases such as diabetes and heart conditions.

This is one of the main findings of a recent study, published in Biochimie, by researchers from Stellenbosch University’s (SU’s) Division of General Internal Medicine, Division of Clinical Pharmacology, and Department of Psychiatry.

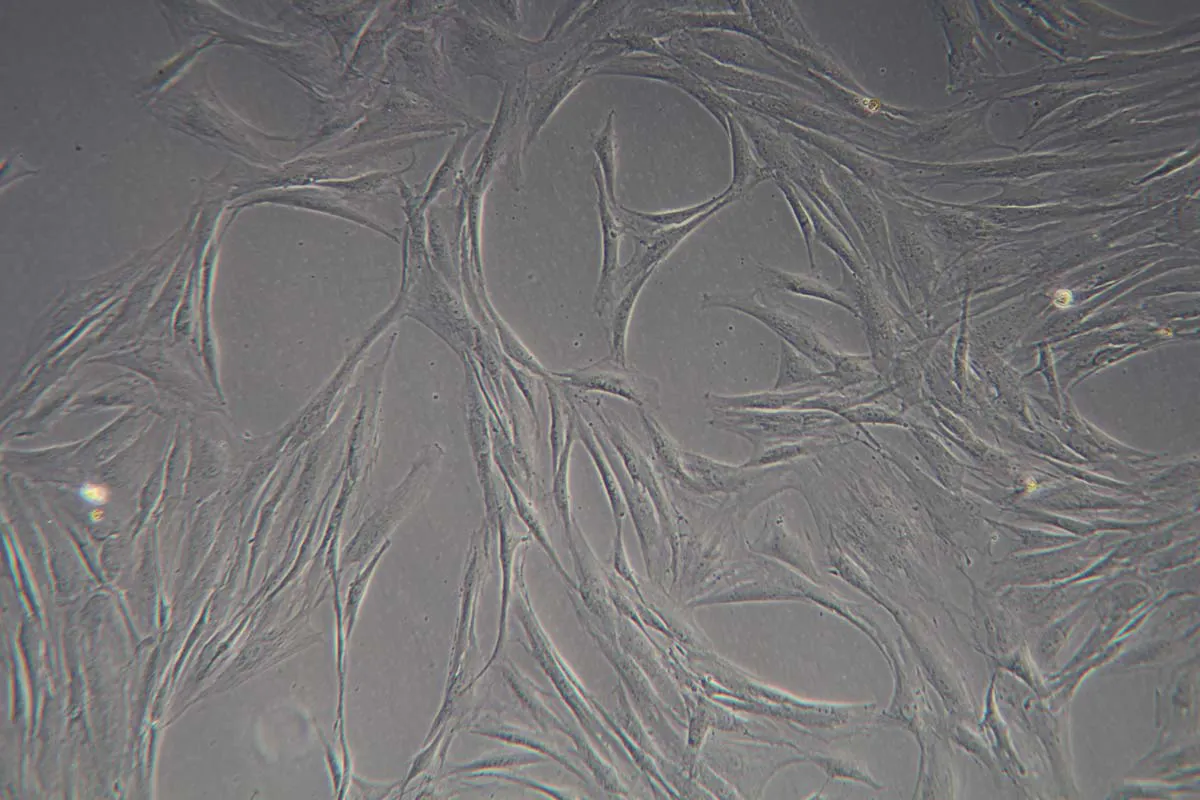

Under the microscope, the researchers compared the inner workings of basal dermal fibroblasts, gathered from the skin of 20 people with PTSD resulting from childhood trauma, to those of another 20 people who also experienced such trauma but did not develop the condition.

Fibroblasts are reasonably robust cells that are widespread in all types of body tissue except the brain. These ‘connector cells’ secrete collagen proteins to support and maintain the structural framework of body tissue. They are activated whenever there is some sort of injury in the body, and are therefore vital to healing and cell regeneration. Basal dermal cells, found at the bottom of the epidermis, produce new skin cells to replace the older ones on the skin surface as they die and are sloughed off.

“In the resting phase, the fibroblasts of the two groups of people looked the same. However, when primed, the PTSD group’s cells did not react when stimulated,” says the lead author and associate professor, Mari van de Vyver of the SU Department of Medicine. Van de Vyver is also a member of the Experimental Medicine Research Group in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences.

“We found that PTSD, a psychiatric disorder, causes functional blunting of patients’ fibroblasts outside the brain. This means that the signalling capacity of these tissue cells are blunted. Patients’ fibroblasts therefore seem to be desensitised to environmental stimuli and do not respond as they should,” Van de Vyver explains.

The research team also noted that there was less movement of calcium in the cells of PTSD patients. This mineral helps build bones and muscles, and improves signalling between nerves. All body cells use calcium to regulate their activity in response to stimuli.

The researchers believe that the functional blunting of fibroblasts could, at least in part, be caused by this lack of calcium movement.

Fibroblasts, as seen under a light microscope. These robust ‘connector cells’ are found throughout the human body, except in the brain. | Image courtesy of Prof Mari van de Vyver and Dr Rohan Benecke

Prof Mari van de Vyver | Photo by Stefan Els

PTSD: Cause and effect

Changes in cellular calcium signalling or in homeostasis in the body could potentially disrupt normal physiological processes and drive the development of PTSD, says physiologist Prof Carine Smith, leader of the Experimental Medicine Research Group and member of the Department of Medicine.

The findings of the study indicate that even if patients receive successful PTSD treatment, typically through trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy and the use of prescribed antidepressants, their bodies might still ‘remember’ the impact of their traumatic ordeal at cellular level.

The authors note that the global rise in cases of somatic disease coinciding with mental disorders such as PTSD is, at least in part, exacerbated by a so-called “allostatic predisposition to stress on a cellular level”. (“Allostatic” refers to the wear-and-tear impact of chronic stress on the body.) They also state that, as yet, relatively little is known about the effect that PTSD could have on body tissue, despite many other diseases being associated with it.

According to an American study, patients suffering from PTSD have a 27% greater risk than others of also suffering from cardiovascular disease, while Scandinavian research shows them to have a 46% greater chance of developing autoimmune diseases.

“It is clear that when it comes to this disorder, it is important to study and treat more than just the brain. PTSD can influence the rest of the body too. We need to do more preclinical and longitudinal studies to confirm the impact of PTSD on body cells, and to establish the point at which the blunting of fibroblasts begins,” notes Smith, the lead researcher involved in the Biochimie paper.

The samples and clinical data used were initially gathered as part of the South African Medical Research Council’s flagship project on the common causes of neuropsychiatric disorders and modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease (the MRC SHARED ROOTS Flagship Project). A research grant for the project was awarded to Distinguished Professor Soraya Seedat of SU’s Department of Psychiatry.

Under Smith’s guidance, the Experimental Medicine Research Group is studying how and why the body’s regulatory (nervous, endocrine, immune, and microbiome) systems become maladapted when a patient is exposed to too much stress and inflammation. The group brings together SU researchers and clinicians who want to better understand the physical impact and root causes of anxiety-related disorders, and why some people are more resilient in the face of trauma and stress than others.

Prof Carine Smith, leader of the Experimental Medicine Research Group in SU’s Department of Medicine. | Photo by Stefan Els

More specifically, Smith’s group studies the role of regulatory system maladaptation in chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, autism spectrum disorder, and PTSD. They use various research models — from cellular to zebrafish, rodent, and human models — to perform disease modelling aimed at therapeutic target identification, drug discovery, drug delivery, and efficacy testing.

Smith’s passion for contributing to research sustainability in Africa led her to establish the SU Zebrafish Unit, which she now directs. More recently, she helped set up the Zebrafish African Network (ZeFAN), through which she hopes to build increased capacity for zebrafish-based research on the continent. Smith is also the vice-chair of SU’s Research Ethics Committee: Animal Care and Use.

The SU Zebrafish Unit, hosted within the Department of Medicine, has been involved in numerous recent projects, including ones on the anxiety-busting properties of green rooibos tea, the adverse effects of ivermectin use, and the influence of Sceletium (a succulent plant also known as ‘kanna’, or Mesembryanthemum tortuosum) on anxiety-like behaviour.

The ‘invisibly wounded’

Working in the field of traumatic stress is like “working with the invisibly wounded who walk a resiliency-vulnerability tightrope in the early and late aftermath of exposure to horrific traumatic events”. This is how Distinguished Professor Soraya Seedat, executive head of the SU Department of Psychiatry, describes efforts by clinicians and researchers to better understand the roots of and possible treatment options for PTSD.

Until 2022, for three cycles, Seedat was lead of the South African Research Chair in PTSD. She is currently the director of the South African Medical Research Council’s Unit on the Genomics of Brain Disorders.

She describes PTSD as a mental disorder “unique in the psychiatric diagnostic nomenclature” because it specifically develops after exposure to an external traumatic event.

“It is a multifactorial, neurobiologically, and phenomenologically complex disorder characterised by pre-existing risk factors that predate exposure to a traumatic event,” she adds.

The contemporary understanding of PTSD, she says, is that it is essentially “a disorder of fear extinction”. (Extinction learning is used as part of exposure therapy, which is commonly used to treat pathological fear. During extinction, individuals learn a new association with the given stimulus that inhibits the expression of the original fear memory.)

“Fear and anxiety in individuals who meet the criteria for the disorder do not extinguish over time, as reflected by persistent aberrations in pathophysiology, symptomatology, and behaviour.

“There is accumulating evidence that early therapeutic manipulation of extinction can interrupt fear and memory consolidation, thereby attenuating trauma memories and reducing the risk for the subsequent development of PTSD. Thus, the influence of traumatic stress on memory formation is a critical nexus in the genesis of PTSD in individuals exposed to traumatic events.”

Although it affects people worldwide, PTSD is especially prevalent in areas with a high prevalence of interpersonal trauma, war, and armed conflict, such as sub-Saharan Africa. Seedat’s own earlier research showed that, compared to men, women have double the risk of developing PTSD, as well as a greater symptom burden, a longer course of illness, and poorer quality-of-life outcomes.

“The preponderance of PTSD in women reflects a convergence of biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors, such as culturally influenced gender roles that may impact on PTSD symptom expression in women,” she notes.

In 2023, after 20 years of working in the field, Seedat received an MPhil in Applied Ethics (Bioethics) from SU for her thesis on the ethicality of current therapeutic treatment options, in which she proposed a bioethical framework for such interventions.

“Prevention is better than cure, but it is only better when the preventive intervention in question has solid scientific evidence for effectiveness, safety, acceptability, accessibility, affordability, and scalability, and produces positive long-term individual-level and societal-level impacts,” she emphasises.

“There are a myriad of ethical complexities facing preclinical interventions for PTSD. Of primary importance are the inherent ethical challenges linked to false-positive identification and the dangers linked to identifying at-risk individuals, the impact of memory-modulating interventions on memory recall and personal identity, and the social implications associated with early intervention.”

There is a significant body of research on the preventive science of PTSD, and on the ethical quandaries of memory modulation. According to Seedat, the wider ethical issues around PTSD prevention must be addressed through the development of consensus bioethical frameworks.

“It should be co-produced by mental health researchers, clinicians, other healthcare providers, and individuals with lived experience of trauma and their families to allow for true advances to be made towards optimising the benefits and minimising the risks of preventive interventions,” Seedat says.

To this end, she believes that research on the therapeutic prevention of PTSD should include the dimensions of self-determination, personal liberty, and informed consent for participants. It should be beneficial and non-maleficent, with cases being treated in a confidential, professional, and socially responsible manner by the professionals involved.

Click here for a list of PTSD-related and other projects that the Department of Psychiatry is pursuing.

Prof Soraya Seedat | Photo by Stefan Els

What is PTSD?

- While most people are somehow resilient enough not to be affected adversely by traumatic events such as violent crime, interpersonal violence or a severe car crash, some develop PTSD after living through or witnessing such instances. It can even manifest in individuals who merely learn that something terrible has happened to a loved one or friend, or to medical personnel, police officers, and the like who repeatedly treat and comfort survivors of traumatic incidents.

- The fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (2022) groups PTSD symptoms into four distinct clusters: re-experiencing, avoidance, negative cognitions and mood, and arousal.

- Typical symptoms include flashbacks, uncontrolled thoughts about the incident, nightmares, severe anxiety, and panic attacks.

- To be diagnosed with PTSD, the associated symptoms must persist for more than a month and “result in clinically significant distress or impairment in the individual’s social interactions, capacity to work or other important areas of functioning”.

- Traumas involving interpersonal violence carry the highest risk for the development of PTSD.

- Research has shown the COVID-19 pandemic to be associated with increased rates of PTSD among healthcare workers. The latest systematic review and meta-analysis revealed 34% of healthcare workers to have experienced PTSD symptoms, with 14% having experienced the disorder in its severe form.

The history of PTSD treatment

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was first recognised as a legitimate disorder in 1980 in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

The word “trauma” has Greek roots and means “wound” or “hurt”. Descriptions of psychological trauma date back to ancient times. It was only in the late 19th century, however, that psychoanalysts Pierre Janet and Sigmund Freud, in their clinical descriptions of hysteria and neuroses, made explicit the causal link between these states and a patient’s prior experience of psychological trauma, including sexual trauma. While a remarkable observation for the time, strong opposition to this hypothesis censored further clinical and research discovery.

It was only in the aftermath of World War I that adverse psychological reactions in male soldiers to the horrors of combat and war were recognised. This attention fluctuated over time, waxing after the Vietnam war when soldiers’ and veterans’ suffering of traumatic stress, as well the management thereof, came into focus. Also, it was in the wake of the Women’s Movement that traumatic stress phenomena in women and child survivors of sexual and domestic violence were first acknowledged.

The early intervention movement in psychiatry began and gained momentum in the field of psychosis in the early 2000s when the World Health Organization and the International Early Psychosis Association collaborated to develop an international consensus statement. The latter was based on the premise that prompt and early interventions for patients and their carers, families, and significant others recognised individuals’ rights to respect, citizenship, support, and social inclusion. Since then, the effectiveness and safety of early interventions have been tested, and the benefits of each evaluated.

Types of treatment

In the realm of prevention, ‘primary prevention’ refers to intervention before a traumatic event occurs, and includes efforts to prevent the event itself. ‘Secondary prevention’ refers to interventions between the occurrence of the traumatic event and the development of PTSD, while ‘tertiary prevention’ involves interventions after the first symptoms of PTSD have appeared. The aim of the latter interventions, which overlap greatly with treatment, is to prevent further decline and to reduce disability in the patient.

Source: Prof Soraya Seedat’s thesis

In numbers

- Globally, around 70% of individuals experience at least one traumatic event in their lives, with the majority occurring early in life.

- While the vast majority of adults and youth exposed to a traumatic event will recover spontaneously, about a third will experience enduring PTSD symptoms over many years. In multi-national population surveys from the World Mental Health Surveys Initiative, the cross-national lifetime prevalence of PTSD among trauma-exposed adults was found to be 5.6%.

- In sub-Saharan Africa, the overall pooled prevalence of probable PTSD among adults has been estimated at 22%.

- There is an extremely high prevalence of PTSD among internally displaced people in sub-Saharan Africa, according to a recent Ethiopian study. The prevalence ranged from 12% in Central Sudan to 86% in Nigeria. Eight of 11 studies found a prevalence greater than 50%. These prevalence rates are much higher than those in similar studies conducted in other regions.

Many young people will experience trauma — an event during which they feel very scared for themselves or for someone else. In certain cases, this will lead to mental health difficulties such as PTSD. | Video courtesy of the UK Trauma Council

The research initiatives reported on above are geared towards addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal number 3, and goals number 1 and 3 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Useful links

SU’s Experimental Medicine Research Group

SU’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences

The South African Medical Research Council’s Unit on the Genomics of Brain Disorders

Post-traumatic stress damages skin cells involved in healing

Prof Carine Smith’s inaugural lecture (2024)

Prof Carine Smith focuses on proper functioning of body’s regulatory systems

How PTSD went from ‘shell-shock’ to a recognised medical diagnosis

Can trauma be inherited through genes?

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

South Africans in a rage — can we work together and overcome the trauma within us?

X (formerly Twitter): @MatiesResearch, @SUHealthSci and @StellenboschUni