Realigning Conservation and Development

21 Mar 2022

The fragility of business models for Africa’s protected areas has been exposed by continent-wide closure of the tourism sector in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. These areas have traditionally relied on three sources of funding – subsidies from national governments, tourism-related revenues such as entrance fees and leasing fees for lodges, and international aid. National funding for African protected areas has always been modest. During the lockdown, tourism revenue disappeared, and multilateral aid flows were redirected to Covid-related priorities.

Not only were protected areas financially devastated by the lockdowns, but so were many private and community managed conservation areas. These areas may have more diversified business models – offering a diversity of wildlife goods and services – but their ability to bring in customers and to sell products such as wild meat was severely constrained. The impact on rural employment and livelihoods was significant.

The lockdown of the wildlife economy across Africa has served as a wake-up call for wildlife policy makers and stakeholders. Even before the pandemic, the state of wildlife in Africa was precarious. In Kenya, wildlife numbers have been declining for decades being outcompeted by more commercially lucrative livestock ranching and crop farming. In South Africa, various wildlife practices, notably captive breeding of lions and rhinos, were being questioned. The lockdown has given us opportunity to reflect seriously on the role that wildlife can play in supporting development. Africa’s wildlife economies could be a means to realign conservation with development.

2022 must be the year of renewal for Africa’s wildlife economy – recovery of wildlife tourism and diversification of wildlife products to increase benefits and reduce risk. For this to happen, there must be a fundamental shift in the way we conceptualise ideas of “conservation” and “sustainable use”.

Conservation through Sustainable Use

The critical nexus between conservation and development was first articulated by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in its 1980 World Conservation Strategy, subtitled Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development. The Strategy set out a vision of conservation that directly linked the management of nature to human betterment:

Conservation is… the management of human use of the biosphere so that it may yield the greatest sustainable benefit to present generations while maintaining its potential to meet the needs and aspirations of future generations.

Thus, conservation is positive, embracing preservation, maintenance, sustainable utilization, restoration, and enhancement of the natural environment…

Conservation, like development, is for people; while development aims to achieve human goals largely through use of the biosphere, conservation aims to achieve them by ensuring that such use can continue.

Conservation aims to achieve human goals by ensuring that the use of the nature is sustainable. In other words, to conserve is to use nature sustainably for human betterment. Conservation is what makes development sustainable. The nexus between conservation and development was clearly set out in the three conservation objectives of the World Conservation Strategy:

- Maintain essential ecological processes and life-support systems… (on which human survival and development depend)

- Preserve genetic diversity… (on which depend the security of the many industries that use living resources)

- Ensure the sustainable utilization of species and ecosystems… (which support millions of rural communities as well as major industries)

At the African Wildlife Economy Institute (AWEI), we recognise that wildlife economies have the potential to deliver these conservation objectives in Africa and, in so doing, to align conservation with development. This requires research and engagement from the ground up, focusing on restoring and rewilding landscapes through the provision of wildlife goods and services that not only conserve nature but also enhance climate resilience, rural livelihoods, and community well-being. The wildlife economy is a complex system which needs to be understood and strengthened at multiple levels from the field to local communities to national capitals to international policy processes.

Conservation and Sustainable Use

Unfortunately, the critical nexus between conservation and development evident in the conservation objectives of the World Conservation Strategy is no longer widely recognised or understood. This may well be in part because the 1992 UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) recrafted these three conservation objectives into three biodiversity objectives as follows:

- the conservation of biological diversity

- the sustainable use of its components

- the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources

In so doing, the CBD explicitly separated the conservation of biodiversity from the sustainable use of ecosystems and species. This recrafting, whether international or not, fundamentally removed the IUCN understanding that it is conservation that ensures that development is sustainable, i.e., through promoting the sustainable use of living natural resources.

Most interestingly, the only explicit mention of sustainable development in the CBD focuses on areas next to protected areas:

8.e Promote environmentally sound and sustainable development in areas adjacent to protected areas with a view to furthering protection of these areas

In this phrasing, sustainable development is seen as a means to protect areas outside of legally protected areas rather than as a means to benefit the people living there.

This unfortunate recrafting of IUCN’s conservation objectives into the CBD’s biodiversity objectives has had profound unintended implications for conservation in Africa. Specifically, international aid in response to the Convention has been directed to protecting areas across Africa from development rather than toward promoting human betterment through sustainable use. Indeed, most of the biodiversity funding from the Global Environment Facility and from bilateral donors has been earmarked for Africa’s protected area system. Little funding – internationally or nationally – has supported conservation through sustainable use in support of sustainable development.

That said, the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development clearly affirms the critical nexus between sustainable use and development:

We envisage a world in which… consumption and production patterns and use of all natural resources – from air to land, from rivers, lakes and aquifers to oceans and seas – are sustainable… We are therefore determined to conserve and sustainably use oceans and seas, freshwater resources, as well as forests, mountains and drylands…

Sustainable use of ecosystems and species is a priority for governments, as reflected in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This is so, even though we now must use the more cumbersome terminology of ‘conservation and sustainable use.’ Sustainable use is explicit in the two biodiversity goals, SDGs 14 and 15:

- Goal 14. Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development

- Goal 15. Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss

The 2030 Agenda and its SDGs – with their support for sustainable consumption and production and for the sustainable use of natural resources – provides the policy mandate for the work of the African Wildlife Economy Institute.

The value proposition for wildlife economies in Africa

Wildlife economies have the potential to realign conservation and development across Africa. Wildlife tourism is a key element of this economy and rebuilding this sector post-pandemic is a clear area for growth and renewal. At AWEI, we are particularly interested in promoting intra-Africa tourism which is becoming increasingly more feasible with the creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area.

Wildlife economies have the potential to realign conservation and development across Africa. Wildlife tourism is a key element of this economy and rebuilding this sector post-pandemic is a clear area for growth and renewal. At AWEI, we are particularly interested in promoting intra-Africa tourism which is becoming increasingly more feasible with the creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area.

The value proposition for wildlife economies in Africa, however, is much greater than photographic tourism. This is already evidenced in the large utilisation of Africa’s wild resources including, fishing, foraging, forestry, and hunting. Some of this use is sustainable, some is not. Some is legal, some is not. AWEI aims to focus on how to enable sustainable and legal use of wild resources that support landscape rewilding in support of conservation, climate resilience, livelihoods, and communities.

In 2022, we will be addressing key opportunities such as the development of a sustainable wild meat sector as called for by the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity at their last Conference in 2018. We will also be supporting dialogues at the national level – in countries such as Kenya, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe – to enhance the enabling policy environment for the wildlife economy.

Importantly, this year, we need to start a serious conversation about hunting. Unlike fishing and foraging, hunting has become a highly emotive subject with some governments like Kenya banning it altogether, others like Zimbabwe focusing on foreign hunters over citizens, and others like the UK planning to ban the import of hunting trophies from Africa. Yet, hunting, whether legal or illegal, is primarily done for food and takes place across this continent. This is because hunting, like fishing and foraging, is an integral part of our relationship with our living planet – a relationship that is economic, social, cultural, and spiritual.

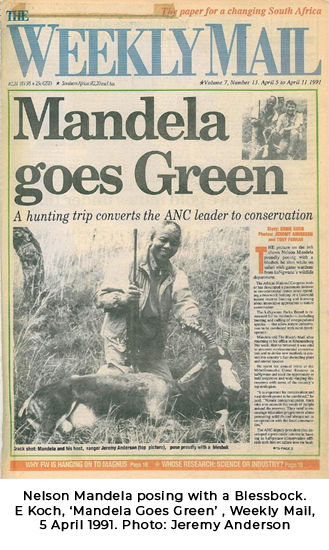

In the coming year, AWEI will be supporting research and dialogue about the centrality of wild harvesting – including hunting – to conservation and, in turn to development. As recognised in the World Conservation Strategy “fish and other wildlife, forests and grazing lands… support millions of rural communities as well as major industries.” AWEI will be exploring how we can enable sustainable and legal use of wildlife to further development across Africa while ensuring that wildlife is conserved. As Nelson Mandela said after hunting a blesbok, “It is important for conservation and rural development to be combined.”

Francis Vorhies, AWEI Director

Originally published by Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation here

-

Prof Francis Vorhies

Director & Professor Extraordinary

We support the free flow of information. Please share:

More content

-

What Foot and Mouth Disease-free means for South Africa’s game meat trade

Ms Lydia Daring Bhebe…Explore the latest developments in South African provinces achieving and maintaining Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) free status…

Articles -

The world wildlife trade regulator is 50 – here’s what has worked and what needs to change

Daniel Challender…Most countries implement Cites, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora as…Articles -

Enabling Sustainable Wildlife Trade

Prof Francis VorhiesEnabling sustainable wildlife trade is a key policy measure for growing Africa's wildlife economy. In this respect, CITES…

Articles -

Has CITES become too complicated to be effective?

Prof Francis VorhiesGovernments agreed to the text of CITES in the 1970s, which is quite straightforward. However, the agreement’s implementation…

Articles -

From poachers to providers: Can Africa's wild meat market save wildlife?

Dr Wiseman NdlovuHave you ever considered how wild meat could be more than just a cultural staple but also a…

Articles -

As a fellow of the African Wildlife Economy Institute (AWEI), I am excited to attend the upcoming 3rd…

Articles -

A theory of change to improve conservation outcomes through CITES

Dr Michael 't Sas-Rolfes…Here we articulate the implied theory of change (ToC) underpinning the design and operation of CITES (Convention on...

2025Research -

Wild Meat Value Chain Integration Systems: Opportunities for Value Chain Formalisation and Scaling in Africa

Dr Wiseman Ndlovu…Establishing a legal, safe and sustainable wild meat sector promises to potentially reduce demand for illegally sourced meat...

2025Research -

AWEI's 2024 Wildlife Economy Dialogue Series

Ms Emily TaylorRediscover 2024: A year of insight and inspiration

In 2024, AWEI proudly hosted three ground-breaking dialogue series in…

Articles

Get updates by email

Through impactful research, stakeholder engagement, and professional development, AWEI is supporting the wildlife economy across Africa. Please subscribe for occasional updates on our work and forthcoming events.

Sign up for a quarterly dose of AWEI insights

In a complex and changing world, AWEI generates strategic ideas, conducts independent analysis on wildlife economies, and collaborates with global scholar-practitioners to provide training and expertise for biodiversity conservation, climate resilience, and inclusive economic opportunities in Africa.