Scaling up Africa’s elephant economy

Introduction

African elephants have provided valuable products that have been traded across the world for thousands of years. As recently as the 1980s, elephant products such as ivory, hides, and meat were routinely traded in countries such as Kenya, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. Small businesses in Bulawayo made wallets and briefcases. Curio shops in Victoria Falls sold ivory jewellery and ornaments. Elephant meat harvested in South Africa was sold to tourists and provided to local communities. These small businesses and the jobs and taxes they paid are now gone. Elephants are more abundant today in several African countries, yet we see continued resistance to using elephant products. Could the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) provide opportunities for revitalising and scaling up Africa’s elephant economy?

Launched at the end of 2022 under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the GBF includes bold new targets for the use of wild species. Could these targets provide a pathway for African countries to unlock the economic potential of elephants?

This brief first reviews the relevant GBF targets for the use of wild species. It then presents various products that could come from elephant use. This is followed by a case study on the previous use of elephants in Kruger National Park in South Africa. The brief concludes with an analysis of the trade measures in place for African elephants under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), highlighting opportunities for facilitating sustainable and legal trade of elephant products.

The global targets for wildlife use

The GBF – formally the Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and marketed as the Biodiversity Plan for Life on Earth – includes a goal to sustainably use biodiversity which echoes the CBD’s sustainable use objective. Interestingly, however, the GBF explicitly emphasises the use of wild species. Of particular importance to the potential for scaling up an elephant economy are Targets 5 and 9. These read as follows:

- Target 5 – Ensure that the use, harvesting and trade of wild species is sustainable, safe and legal, preventing overexploitation, minimizing impacts on non-target species and ecosystems, and reducing the risk of pathogen spill over, applying the ecosystem approach, while respecting and protecting customary sustainable use by indigenous peoples and local communities.

- Target 9 – Ensure that the management and use of wild species are sustainable, thereby providing social, economic and environmental benefits for people, especially those in vulnerable situations and those most dependent on biodiversity, including through sustainable biodiversity-based activities, products and services that enhance biodiversity, and protecting and encouraging customary sustainable use by indigenous peoples and local communities.

These targets call on governments, entrepreneurs, communities, and other stakeholders to ensure that the management, use, harvesting, and trade of wild species are sustainable, legal, and beneficial to people. This is to be accomplished through sustainable biodiversity-based activities, products, and services and by respecting, protecting, and encouraging customary sustainable use by local communities.

What are the possibilities of meeting GBF Targets 5 and 7 through sustainable elephant-based activities, products, and services?

Sustainable uses of elephants and elephant products

Elephants offer an array of goods and services that can benefit people – from both non-consumptive and consumptive uses. Some non-consumptive uses of elephants, notably photographic tourism, are fairly well developed. The same cannot be said about consumptive uses of elephant products due to regulatory and trade barriers that are driven by ideological opposition to the trade. Possible uses of elephants that could be scaled up include the following:

- Ecotourism – As one of Africa’s ‘big five’ iconic species, elephants are a key draw for tourists who want to see and photograph African wildlife. Elephants can be viewed in many countries across the continent.

- Hunting – The ‘big five’, including elephants, are the animals that hunters consider the most challenging to track and hunt on foot. Hunters, of course, hunt live animals, and as such, they are not always successful in their pursuits. Elephants are hunted in Botswana, Cameroon, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

- Dung – Elephant dung is used as medicine (headaches and nose bleeds), mosquito repellent, fuel, paper, and soap.

- Milk – Though lactating elephants will produce ten or more litres of milk a day, it is not easy to collect. Thus, without innovative harvesting methods, milk from wild elephants is unlikely to be a viable product.

- Meat – Elephant meat has always been consumed by humans, with records of harvesting going back over a million years. Today, elephants continue to be harvested for their meat, notably in Central African countries. In some countries, meat from hunting safaris is also provided to local communities.

- Fat and bone marrow – Elephant fat and bone marrow have also always been consumed by humans. Fat can also be used for body creams, cosmetics, and soaps.

- Hide – Elephant hide is thick and has a variety of uses, including belts, handbags, wallets, boots, chair coverings, luggage, golf bags, jewellery, and traditional products. medicinal Some of these products are legally traded today.

- Trophy – Several parts of an elephant can be kept as a trophy from a safari hunt, including the head, the trunk, and the ivory tusks.

- Ivory – Elephant ivory comes from the tusks, which are teeth that continue to grow. Ivory has many uses, including art, jewellery, figurines, sculptures, piano keys, cufflinks, combs, game pieces, decorative boxes, pipe stems, knife handles, pipe stems, billiard balls, buttons, and tools. Some of these are legally traded today.

A sustainably managed population of elephants could provide a combination of ‘non consumptive’ uses, such as ecotourism and dung products, along with ‘consumptive’ uses, such as hunting, meat, fat, hide and ivory. Sustainable management of elephants, along with other wild species, needs to start at a landscape level by managers in areas where elephants live – whether public, community, or private. Through global value chains, elephant-based activities, goods, and services could generate revenues for the management and use of elephants for human benefit.

Using elephants in Kruger National Park

What if we could manage the supply of elephant goods and services sustainably? What would an elephant economy look like? We can get an idea by looking back at the elephant management programme that was in place in Kruger National Park (KNP) before the introduction of strict trade measures under CITES in 1990.

Drawing from a 2008 book on elephant management in South Africa, one study available online provides insights into the economics of the KNP elephant management programme. It contains thought-provoking information on the potential profitability of elephant culling in KNP. The observations merit reprinting here for consideration by policymakers and those interested in scaling up the sustainable trade of elephant-based activities, products, and services. The study noted that:

- Elephant products are potentially valuable. In KNP, only the blood and intestines were left in the field, and the rest were used

- The ivory is the most valuable single product,

- but if the hides are properly treated, they represent an almost equivalent value.

- All meat was used either for biltong or for a canned meat product. Biltong and canned meat were sold to tourists, while the cans were also issued to field staff as rations.

- Excess carcass fat was rendered and sold to the cosmetic industry,

- while all other parts of the carcass were made into carcass meal for sale to the agricultural industry.

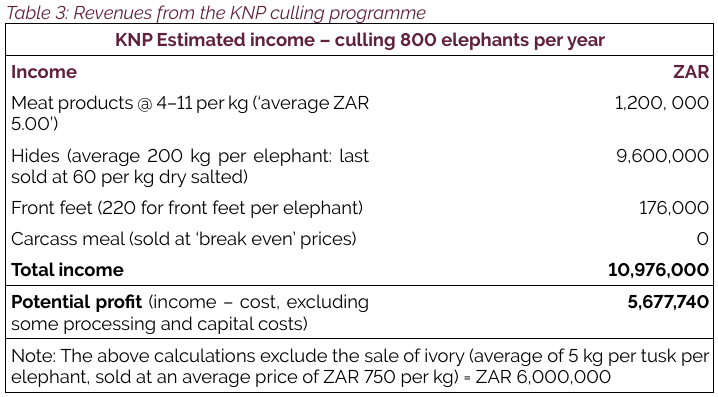

- Considering all of the potential income, excluding ivory, 800 elephants would generate about ZAR 10,976,000 per year. This provides a profit of ZAR 5,677,740, or just over ZAR 7,000 per year per elephant (excluding recapitalisation of the abattoir).

- The addition of ivory to the income would effectively double the profit.

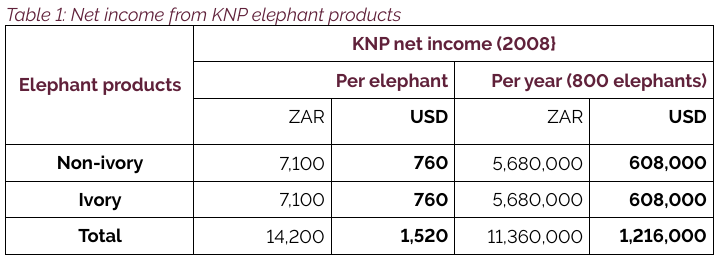

As summarised in the table below, if we add the income from ivory to the net income from non-ivory products and convert it to 2008 US dollars, then KNP made an annual profit from its elephant products of roughly $1.2 million, or about $1.8 million in today’s money. This excludes any imputed value to elephants from ecotourism and the potential revenues that theoretically could have come from hunting.

Hides, biltong, canned meat, fat, carcass meal, and ivory were all sold commercially by KNP. These products were sold to tourists, the cosmetic industry, the agricultural industry, and international buyers. Some meat products were also consumed by park staff and distributed to neighbouring rural communities.

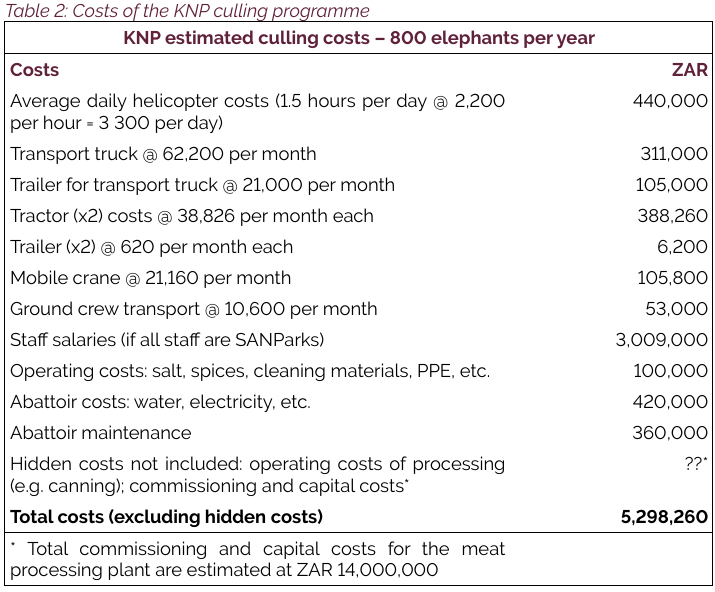

As follows, the study provides more detailed tables on costs and revenues adapted from a 2005 report of the estimated costs and revenues of KNP’s elephant culling programme. These tables present a profit/loss analysis that demonstrates that the programme was viable:

These calculations indicate that KNP’s elephant culling programme was more than able to cover its costs even without the sale of ivory. With the sale of ivory, profits for KNP increased considerably from roughly ZAR 6 million to ZAR 12 million.

If we were to add to these revenues those that KNP earned at the time from elephant related ecotourism, as well the potential revenues that KNP could have earned from sport hunting and live sales, it appears that there was – and still is – a real potential for a financially-sustainable elephant economy. More revenue could also be added to the local economy by processing elephant parts into various finished products, as highlighted in the previous section above.

Although ivory has traditionally been exported for processing in the Far East, there are lessons to be learned from Botswana’s approach to diamond processing. Diamonds from Africa are mostly cut and polished in Europe and India, but the Botswana government has recently supported more cutting and polishing taking place in the country. Similar support for adding for adding domestic value to ivory, leather and other elephant products could provide skilled jobs and add considerable value to local economies.

A vibrant elephant economy could supply a large array of elephant goods and services to both domestic and international customers. Integrating elephant products into global value chains, however, will require removing non-tariff barriers to trade.

Liberalising trade in elephant products

The market for elephant products is restricted by domestic regulations and international trade measures. Governments interested in opening up this market will need to review their domestic legislation, regulations, and regulatory practices to identify barriers which could be lifted to enable legal harvesting, use, and trade.

They will also need to collaborate with other like-minded governments to address international trade barriers, notably in place under CITES. In this section, we focus on CITES trade barriers and suggest possible pathways to address these barriers while continuing to ensure that the trade is legal and sustainable.

From the start of CITES in 1975 to 1990, African elephants were listed in Appendix II. Since 1990, most African elephants have been listed in CITES Appendix I. Since 1997, however, elephants from four countries – Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe – were placed back on Appendix II, albeit with additional trade measures as explained further below.

CITES sets out the measures for trading Appendix I and II species, including elephants. Adherence to these measures is the most direct pathway to enabling sustainable and legal trade. These include the following:

- Issuing Appendix I and II export permits – For species listed in Appendices I or II, exporting countries are required to issue export permits based on a determination that the export is not detrimental to the survival of the species, i.e., that the trade is sustainable, and that the product was legally acquired.

- Issuing Appendix I import permits – For species listed in Appendix I, importing countries are required to issue import permits based on a determination that the purposes of the import are not detrimental and that the use is not primarily for commercial purposes.

For Appendix I listed elephants, the pathway to trade involves the issuing of an export permit and an import permit based on a determination that the trade is legal, sustainable, and not primarily for commercial purposes. Countries interested in trading Appendix I species need to put in place robust and transparent processes to enable the permits to be issued and the trade to take place.

For Appendix II listed elephants, the pathway to trade, in principle, is less complicated, with only the exporting countries required to issue export permits based on a determination that the trade is legal and sustainable. Again, trade could be facilitated by putting in place a robust and transparent process to issue these permits.

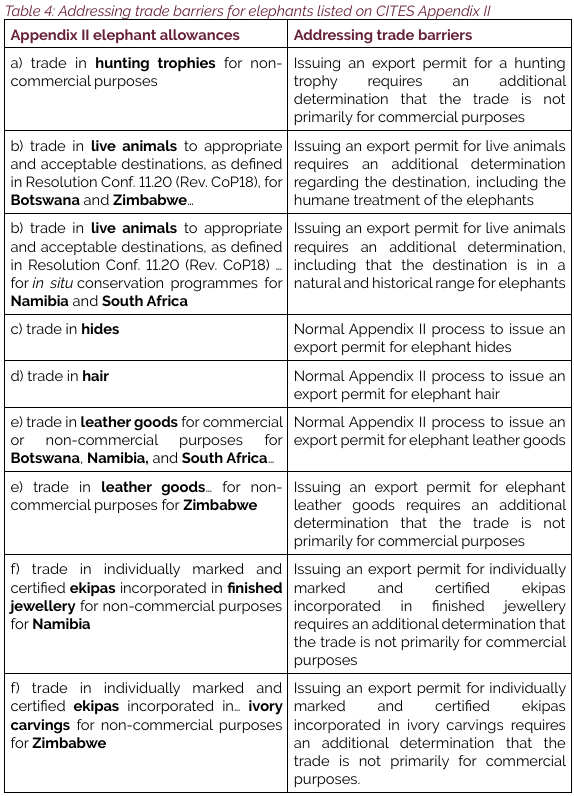

Decisions by the CITES Parties, however, have made the trade in Appendix II elephants from the four southern African countries more difficult by the inclusion of added barriers for particular elephant products. Under the current CITES listing, each of these additional barriers needs to be addressed individually, as suggested in the following table:

Further, other elephant products not mentioned in the table above, such as meat, fat, and bone marrow, are subject to the normal export permit requirement for an Appendix II listed species – i.e., a determination that products are legally acquired and not detrimental to the survival of the species. Hence, CITES-compliant trade of elephant products is indeed possible for all African countries through Appendix I measures and Appendix II measures for the four southern African countries with the additional barriers outlined.

Developing African-wide value chains for elephant products

To illustrate the potential for CITES-complaint trade in elephant products, consider the value chain for elephant leather goods. Elephant hides can be sourced from hunted or harvested elephants. These can then be sent to a tannery for processing into leather. The leather, in turn, can be used to make belts, boots, billfolds, and other leather products. With the African Continental Free Trade Areas (AfCFTA) facilitating the elimination of non-tariff barriers, it could be possible for several African countries to participate in the value chain for elephant leather.

Assume that a game hide tannery is operating in Botswana and would like to expand its operations. It may already be sourcing elephant hides from domestic hunts and harvests. It could, however, also source hides from hunts or harvests in other African countries. For the exporting countries, these elephants could be listed on Appendix I or II.

For an Appendix II country, like Zimbabwe, an import permit for the hide is not required, but an export permit that confirms that the trade is sustainable and legal is required. If Zimbabwe, on the other hand, wanted to process its hide into leather and then export the leather to Botswana or elsewhere, the CITES annotation noted above would require that Zimbabwe further confirm that the export is non-commercial. Given this trade barrier, Zimbabwe might prefer to export its raw elephant hide to Botswana for tanning.

To source from a country like Tanzania with its elephants on Appendix I, both import and export permits are required. Tanzania’s export permit for hides from hunted or harvested elephants would confirm that the trade is sustainable and legal. Botswana’s import permit would confirm that the purpose of the import – to secure a supply of hides for processing into leather – is sustainable and further that the important aims primarily to benefit people through the processing of elephant leather goods.

Botswana could use its elephant leather domestically to make products, or it could export it to another country, such as South Africa. If Botswana exports the leather, only a CITES-compliant export permit is required. If Botswana or a country like South Africa makes products from elephant leather, these could be traded domestically or, if exported, would also require a CITES-compliant export permit.

Applying CITES trade measures within the context of the AfCFTA could develop an African-wide sustainable, legal, and beneficial value chain for elephant leather products. Likewise, similar African-wide value chains could develop for elephant meat, fat, bones, and even ivory.

Pathways to scaling up Africa’s elephant economy

GBF Targets 5 and 9 call on governments and other stakeholders to ensure that the management, use, harvesting, and trade of wild species is sustainable, legal, and beneficial to people. The trade measures for species listed on CITES Appendix I facilitate assurance that trade in these species is indeed sustainable, legal, and beneficial. Hence, a clear pathway to scaling up Africa’s elephant economy is to enable and promote CITES-compliant trade in elephant products.

CITES-compliant trade requires establishing robust and transparent processes for issuing the required export and import permits. Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe could further develop these processes by promoting trade of wild species among themselves, including promoting trade of elephant products such as hides or meat. By operationalising a clear and streamlined permitting process for exports and imports – also supported by AfCFTA – these countries could establish best practices for legal and sustainable trade in wildlife products.

The trade in elephant products could then be expanded to other African countries that are interested in developing their elephant economies. Prospects include countries like Tanzania or Zambia with sizable elephant populations and elephant management programmes that include hunting. As the elephant economy expands across the continent, countries with or without elephants may then also start to participate in African markets for sustainable and legal elephant products. With the right incentives, there is an opportunity to add value locally and turn Africa’s elephants into a significant economic opportunity. African elephant products have been a source of wealth for centuries, and many populations are well-managed and can be harvested sustainably. What is needed is African leadership in implementing GBF Targets 5 and 9 through adhering to CITES compliant trade measures and, in so doing, to establish and then scale up a sustainable and legal elephant economy across the continent.

References

Convention on Biological Diversity: Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). [Online]. [n.d.]. Available: https://www.cbd.int/gbf. [2024, July 11]

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora: The CITES Appendices. Available: https://cites.org/eng/app/index.php [2024, July 11]

Slotow, Rob & Whyte, Ian & Hofmeyr, Markus & Kerley, Graham & Conway, Tony & Scholes, Robert. 2008. Lethal Management of Elephants, in Elephant Management. 370–405. Available: https://doi.org/10.18772/22008034792.19 and https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376520579_LETHAL_MANAGEMENT_OF_E LEPHANTS

This brief benefited from comments by the AWEI team and CIC Wildlife, and from core support from Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation.

-

Dr Michael Musgrave

Research Associate -

Prof Francis Vorhies

Director & Professor Extraordinary

We support the free flow of information. Please share:

Form coming soon

More content

-

What Foot and Mouth Disease-free means for South Africa’s game meat trade

Ms Lydia Daring Bhebe…Explore the latest developments in South African provinces achieving and maintaining Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) free status…

Articles -

The world wildlife trade regulator is 50 – here’s what has worked and what needs to change

Daniel Challender…Most countries implement Cites, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora as…Articles -

Enabling Sustainable Wildlife Trade

Prof Francis VorhiesEnabling sustainable wildlife trade is a key policy measure for growing Africa's wildlife economy. In this respect, CITES…

Articles -

Has CITES become too complicated to be effective?

Prof Francis VorhiesGovernments agreed to the text of CITES in the 1970s, which is quite straightforward. However, the agreement’s implementation…

Articles -

From poachers to providers: Can Africa's wild meat market save wildlife?

Dr Wiseman NdlovuHave you ever considered how wild meat could be more than just a cultural staple but also a…

Articles -

As a fellow of the African Wildlife Economy Institute (AWEI), I am excited to attend the upcoming 3rd…

Articles -

A theory of change to improve conservation outcomes through CITES

Dr Michael 't Sas-Rolfes…Here we articulate the implied theory of change (ToC) underpinning the design and operation of CITES (Convention on...

2025Research -

Wild Meat Value Chain Integration Systems: Opportunities for Value Chain Formalisation and Scaling in Africa

Dr Wiseman Ndlovu…Establishing a legal, safe and sustainable wild meat sector promises to potentially reduce demand for illegally sourced meat...

2025Research -

AWEI's 2024 Wildlife Economy Dialogue Series

Ms Emily TaylorRediscover 2024: A year of insight and inspiration

In 2024, AWEI proudly hosted three ground-breaking dialogue series in…

Articles

Get updates by email

Through impactful research, stakeholder engagement, and professional development, AWEI is supporting the wildlife economy across Africa. Please subscribe for occasional updates on our work and forthcoming events.

Sign up for a quarterly dose of AWEI insights

In a complex and changing world, AWEI generates strategic ideas, conducts independent analysis on wildlife economies, and collaborates with global scholar-practitioners to provide training and expertise for biodiversity conservation, climate resilience, and inclusive economic opportunities in Africa.