Embracing the economic benefits of eco-system restoration through landmine clearance

5 Sep 2023

A 1995 report from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) declared the African continent as the most severely affected by large-scale landmine laying globally. After decades of landmine clearance activities by humanitarian, commercial and state entities, the most recent reports identify 19 African states in which landmine contamination remains an enduring problem. Mined areas not only represent a risk to life and limb; in addition, they are often representative of lost economic potential and degraded ecosystems, coinciding with communities who have already suffered the devastating effects of conflict, and many of whose economic situations leave them disproportionately vulnerable to climate change and to further degradation of the ecosystems they rely on.

This article examines the importance of addressing environmental and socio-economic considerations cohesively during humanitarian landmine clearance activities, with an emphasis on the economic benefits for affected communities of such an approach.

Humanitarian mine action can be understood as positioned at an intersect between humanitarian and development agendas. The humanitarian priority of mine action is to prevent loss of life; however, the ultimate aim of mine action organisations goes beyond technical mine clearance, with the International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) broadly defining mine action activities as those which “aim to reduce the social, economic and environmental impact of mines, and ERW [Explosive Remnants of War]”.

Within a growing international acknowledgement of the inseparability of human wellbeing and the conservation of healthy eco-systems, opportunities for mine action organisations to engage with environmental and conservation activities and are increasingly recognised on the international stage. This shift aligns with the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030), built on the back of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which specifically recognises the importance of cross-sectoral dialogues and collaboration on ecosystem restoration as a pathway to global sustainability goals.

In Zimbabwe, the most recent estimates give known landmine contamination as standing at 23.51km², with over 26,000 landmines destroyed in 2021 alone. The impacts of this contamination, however, are felt far beyond minefield boundaries. In the case of Zimbabwe, landmines were historically laid over 700 linear kilometres of state border, resulting in an enduring hazardous boundary that continues to pose a threat to children walking to school, local communities farming land, and migratory animals.

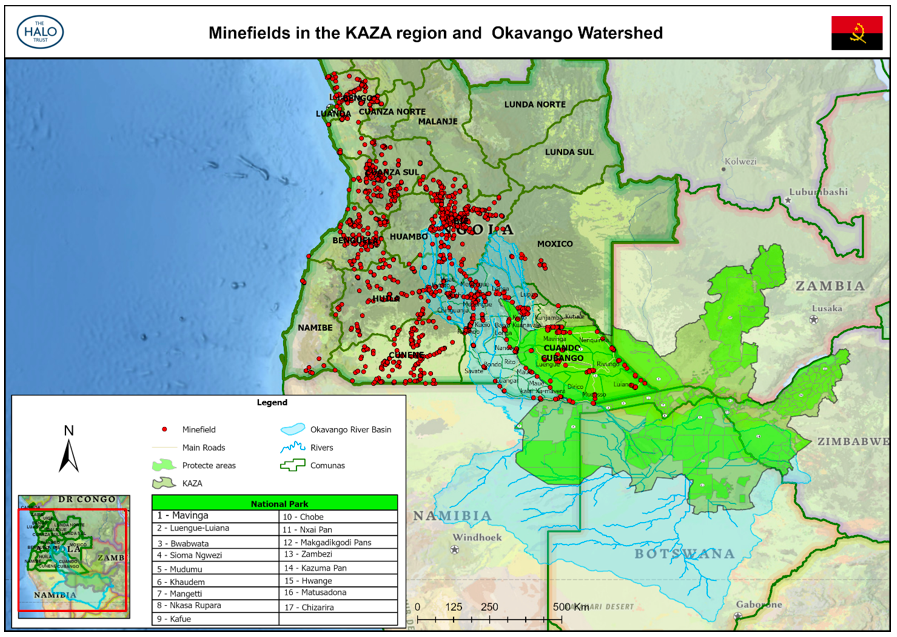

In Angola, the most recent estimates show 40km² of known landmine contamination remains to be cleared. A significant number of minefields in the South East of Angola fall within, or just outside, of the Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA). The KAZA is the largest transboundary conservation area in the world, spanning nearly 520,000km² across five countries in Southern Africa: Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. In Angola, the KAZA area includes the headwaters of the Okavango River Basin, feeding into the Okavango Delta, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Landmine contamination in the headwaters of the Okavango watershed in Angola, including in the National Parks of Mavinga and Luengue- Luiana in Angola, fall within this transboundary protected area.

The following map details some of the known minefields in the central and southern parts of Angola, and their proximity to National Parks and the KAZA region:

The hydrological regime and water quality of the Okavango Delta are heavily influenced by occurrences up-stream, including in Angola. A vital ecosystem for much of Southern Africa, this river system supports large-scale irrigation in neighbouring countries, the eco-system of the Okavango Delta, and subsequently the tourism revenue of national parks within the KAZA conservation area. With water demands on the Okavango increasing, this eco-system is vital to the economy of five Southern African states.

Agricultural and conservation activities in the Okavango basin have both been severely impacted by the presence of landmines, and an early external review of the KAZA conservation project notes that “[T]he presence of landmines in the Luiana Partial Reserve of southern Angola is seen as a major obstruction and limitation towards achieving integrated flow of wildlife and people in the TFCA [Trans-Frontier Conservation Area]”. Landmine clearance activities in the region have adapted accordingly, embracing the benefits of a holistic approach that integrates both social, and ecosystem recovery into the landmine clearance process.

Across the Horn of Africa, communities already suffering from the impact of landmines are faced with one of the worst droughts in decades. Counting on local workforces, access to remote communities and international support, mine clearance organisations are beginning to engage with eco-system restoration activities in recognition of the economic benefits to affected communities; re-establishing native vegetation, restoring soil health, and encouraging the return of local fauna. This process not only aims to encourage biodiversity recovery but also to offer communities essential ecosystem services such as water access, carbon sequestration, and soil erosion control, enabling economic recovery and increasing community resilience to climate change.

Furthermore, the restoration process itself can stimulate job creation, offering roles in demining, ecosystem restoration, construction, and subsequent maintenance. Not only does this provide immediate employment opportunities, but also promotes local ownership and sustainability of land management.

Increased agricultural productivity as previously mined lands are put back to use is a clear economic advantage of the clearance process, along with opportunities for carbon credit schemes alongside the restoration of previously mined areas. Other economic potentials directly related to environmental and conservation activities can be found where clearance takes place in protected areas, on access routes to protected areas, or even where clearance activities will open up conservation opportunities in a much wider region, such as in the Okavango headwaters. In these examples, there are associated economic benefits resulting from opportunities for eco-tourism and sustainable resource extraction. In short, any intervention that leaves the eco-system (and by extension eco-system services) in a more favourable state can, when well managed, be understood in terms of its economic value for the affected community.

The economic benefits of a holistic approach to mine clearance activities additionally can also apply to mine action organisations. In their 2022 report, the Mine Action Monitor observe that international funding for mine action activities has decreased every year from 2017 ($696.3 million) to 2021 ($543.5 million). Mine action operations are traditionally funded in the knowledge that mine action activities are finite, with cessation of funding largely expected at completion of state-wide operations. Whilst other funding mechanisms exist that can be utilised for continuation of environmental activities, key to successful implementation lies in identifying initiatives that allow integrated conservation activities to become self-sustaining. A focus on the economic benefits of conservation not only makes investment more appealing to wider and more diverse pool of potential donors, but ultimately ensures the sustainability of interventions where local communities have economic incentives to take ownership of sustainable land management.

It is useful here to consider adopting a business model concept of ecosystem services that understands the economic sector as ‘ally’ to ecosystem conservation, and takes into account the interrelated nature of human development and ecosystem health. This approach aligns well with global trends, with the goals of the UN Decade for Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030), emphasising the need to identify economic returns from eco-system restoration globally, and encouraging holistic approaches to do so. Furthermore, the Global Biodiversity Framework adopted at the 2022 Biodiversity Conference in Montreal included the adoption of the following clause by participating states:

“Ensure that the management and use of wild species are sustainable, thereby providing social, economic and environmental benefits for people, especially those in vulnerable situations and those most dependent on biodiversity, including through sustainable biodiversity-based activities, products and services that enhance biodiversity, and protecting and encouraging customary sustainable use by indigenous peoples and local communities”.

There is increasing understanding amongst donors to the mine action sector that the livelihoods aspects of mine clearance operations require engagement at an environmental level, which necessarily will require targeted funding opportunities. There is also an increasing recognition amongst conservationists as to the environmental impacts of explosive ordnance, especially in light of recent high profile and well-documented cases in Ukraine.

The priority of mine action activities is to prevent loss of life and limb. However, the ultimate aim of mine action activities is to enable social and economic recovery and restore livelihoods through land release activities. Donors, governments, and private investors are more likely to invest when they can see tangible socio-economic returns alongside environmental recovery, and the most successful interventions are likely to be those that become sustainable due to this economic feedback mechanism.

Author: Emily Chrystie, Global Environment Manager at the HALO Trust

Emily recently completed an MS in the Management of Conservation Areas at the Carinthia University of Applied Sciences with her thesis on: "Opportunities in Mine Action for Mainstreaming of Environmental Protection and Conservation."

We support the free flow of information. Please share:

More content

-

Drivers of hunting and photographic tourism income to communal conservancies in Namibia

Mr Joseph Goergen …Hunting and photographic tourism provide ecosystem services that can facilitate conservation. Understanding factors influencing how tourism industries generate...

2024Research -

SANParks Vision 2040: A New Era for Conservation in South Africa

Mrs Emily TaylorReimagining Conservation: SANParks' Vision 2040

South African National Parks (SANParks) has unveiled its ambitious Vision 2040, a…

Articles -

In defence of wild meat’s place at the table

Tim VernimmenQ&A — Conservation scientist E.J. Milner-Gulland

Sustainable and safe consumption of wildlife is possible, and important for those…

Articles -

The diverse socioeconomic contributions of wildlife ranching

Candice Denner…The diverse socioeconomic contributions of wildlife ranching are increasingly recognized as a vital element of sustainable development, particularly...

2024Research -

A conflict of visions: Ideas shaping wildlife trade policy toward African megafauna

Mr Michael 't Sas-Rolfes…The issue of wildlife trade is a major concern for the conservation of African megafauna, such as elephants...

2024Research -

Barriers to the Participation of the Traditional Leadership Institution in Promoting Rural Agricultural Development

Dr Wiseman Ndlovu…The Traditional Leadership Institution (TLI) is constitutionally recognised to promote rural development in South Africa. It works with...

2022Research -

Elephant in the Room - Why a trophy hunting ban would hurt conservation and development

Dr Francis Vorhies“Trophy hunting, if well managed, conserves wild species and habitats and enhances livelihoods in rural communities.” - Dr...

2024Briefs -

Biodiversity means business: Reframing global biodiversity goals for the private sector

Dr Francis Vorhies…The Convention on Biological Diversity strategic goals direct the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity from global to...

2019Research -

The 33rd Meeting of the Animals Committee of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild…

Articles

Get updates by email

Through impactful research, stakeholder engagement, and professional development, AWEI is supporting the wildlife economy across Africa. Please subscribe for occasional updates on our work and forthcoming events.

Sign up for a quarterly dose of AWEI insights

In a complex and changing world, AWEI generates strategic ideas, conducts independent analysis on wildlife economies, and collaborates with global scholar-practitioners to provide training and expertise for biodiversity conservation, climate resilience, and inclusive economic opportunities in Africa.