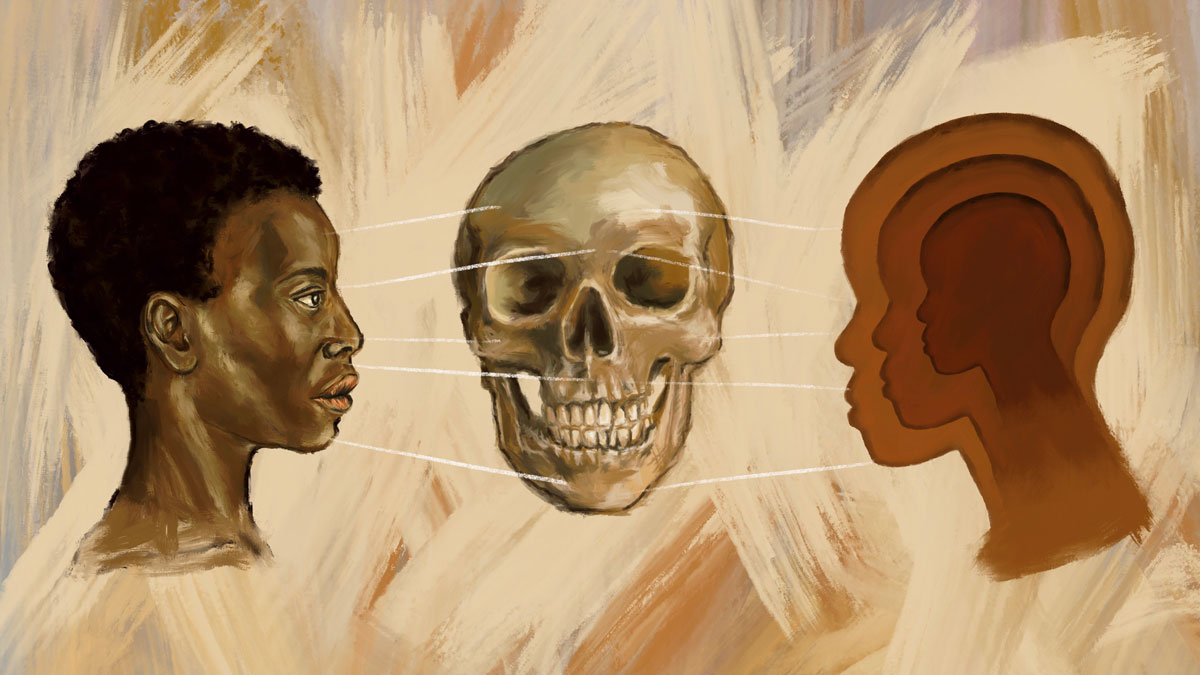

Advances in forensic art explore and preserve our common humanity

Willem de Vries

Illustration by Ronel van Heerden

In her work on projects aimed at restoring personhood for missing and unidentified people of the past — both recent and ancient — Dr Kathryn Smith, Departmental Chair of Visual Arts at Stellenbosch University (SU), is unearthing shared histories and untold stories through art, science, and collaborative work.

“Forensic art is not a discipline as much as a practice or a field of interest,” she says. “Taking into account various boundaries, forensic art is very much on the edge of lots of things. It’s broadly considered a super specialisation of forensic anthropology, as well as forensic odontology. There’s now a tendency to refer to it as ‘forensic facial imaging’, even though art is essential to it.”

Many of the skills in facial reconstruction as a forensic practice have their origin in anatomy and human heritage, says Smith. “As far as I can tell from having looked into its history, it developed in tandem in different spaces where people posed the scientific question whether it is possible to reconstruct someone’s face from their skull.”

Dr Kathryn Smith, with her work The Studio Familiar X0198/1669 which formed part of Between Subject and Object: human remains at the interface of art and science (2014), an exhibition which placed artworks in conversations with artefacts and specimens from anatomy and pathology museums. | Photo by Caroline McClelland

Crafting a career in an emerging field

“The term ‘forensic’ signals ‘applied’. You first have to do the thing that is prefixed by 'forensic'. If you’re a forensic entomologist, you have to be an entomologist before you can apply it to the forensic context,” says Smith.

After being lauded as a Standard Bank Young Artist in 2004, she joined SU in 2006 as head of the fine art division in the Department of Visual Arts. Six years later, she realised a longstanding wish to formalise her interest in forensic cultures and procedures, and immersed herself in her studies at Dundee’s Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification in Scotland. Here, she gained the skills and knowledge she intuited necessary to forge a career in what was to become a many-layered forensic art space.

Upon graduating with distinction in 2013, Smith became the first African to attain an academic qualification in forensic art and facial identification. After returning from Dundee, she spent 18 months back in her role at SU before leaving again to pursue a PhD opportunity at Liverpool John Moores University. Here, she worked as a researcher at Face Lab in the university’s School of Art and Design, contributing to a range of forensic and archaeological casework and museum projects, and teaching on the new MA Art in Science postgraduate programme.

Between September and November of 2020, Smith awaited the outcome of her thesis examination and began to plan her return home, just as the hard lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic began to lift. She set to work realising her longstanding idea of a forensic facial imaging lab that could introduce these skills to students from both art and science backgrounds, and develop a research, service and training programme over time. Pearl Mamathuba, another recent Dundee graduate and a member of the South African Police Service’s facial imaging unit, had reached out to Smith, as she was interested in exploring PhD studies. Together they developed a doctoral research proposal, and Mamathuba secured a full scholarship. Along with an MSc student in Clinical Anatomy who Smith was already co-supervising, VIZ.lab was launched in January 2021, an imaging laboratory based in SU’s Department of Visual Arts.

Forensic art is an unregulated field, and how people train for it is very varied, she remarks. “I liked this idea of being almost like an apprentice in that the training is very artisanal, almost guild-like. Often, people who get into this work in the law enforcement context have been mentored by a senior officer, or they’re the one cop in the charge office who can draw, and then they get put in the position of forensic artist. Yet it’s highly specialised, and people love the work so much because they see it as making a contribution. They often do it voluntarily because there are so few actual full-time jobs in the field, but that comes with its own problems.”

Every Contact Bears a Trace, a soft-ground etching on copper plate (2008) | Photo of her own work by Dr Kathryn Smith

Building relationships

Smith quickly realised that if she wanted to do forensic art in South Africa, she would need to do so within a research environment because of the benefits it holds, such as institutional support and authority. She would also need to sign a service contract with the South African Police Service (SAPS) to be able to formally assist with any cases they receive. This realisation led to, among other projects, the formation of the Western Cape Cold Case Consortium (W4C).

“The W4C is a collaborative, ongoing research project that has proven to be one way of both working closely with Forensic Pathology Services [FPS] and getting cases directly referred from them. It involves exploring the possibilities of multifactorial analysis for complex identification cases within a research context, but with explicit application to the improvement of service delivery.”

Smith notes that FPS, which is part of the Department of Health, and SAPS operate under a memorandum of understanding regarding unidentified cases, as each has a specific mandate. FPS investigates the death and is the custodian of the body; SAPS is responsible for its identification. “FPS and SAPS collaborate in order to do this work. Sadly, this relationship is full of challenges, although there are active attempts to enable better cooperation, especially in the Western Cape, which is also the only province with digitised FPS records.”

Dr Kathryn Smith: “I normally make installation environments, or curate exhibitions. I also extend my interest in curatorship to how I approach my own work. I put together lots of different things in order to explore unexpected relationships and the meaning or knowledge that may be created when unrelated things are made to connect, or familiar things come together in unexpected permutations.” | Photo by Gallo Images/Die Burger/Jaco Marais

The ethics of (non-)ownership

Forensic art distinguishes itself from other art disciplines by occupying a collaborative space in which “the supposedly stable idea of there being a sole author is problematised very productively”, says Smith.

“In forensic art, you’re always working in the service of a law enforcement agency or some other commissioning authority. You certainly never see forensic artists in the employ of government agencies or services sign their work. If you’re a freelance artist, though, you need your name in circulation, yet it’s considered almost unethical to own your work as an individual.

“If I’m interviewing you as an eyewitness and you describe an unknown suspect, I create a visual statement in the form of a face from your recollection,” she explains. “Likewise, if I’m reconstructing the face of an unidentified deceased person, it’s not my artwork. It’s a piece of investigative intelligence, the result of working with data from many different sources, which one can’t possibly own as yours alone.”

Shaping a likeness

Smith is often asked the question, “How does one know, when creating a forensic likeness of a person, that it is accurate?”

In answer, she explains that forensic artists do validation studies of anatomical data and utilise medical imaging technologies. “Because of the developments in technology, I could now conceivably put you in a CT scanner, scan your head, and then segment the scan to separate hard tissue from soft tissue, and processing each set of data into virtual 3D models, a skull and a face surface. I would then hide the ‘face’ model so it doesn’t interfere with my study and do a ‘blind’ reconstruction of the skull using existing methods, and then compare my reconstruction with the 'real' face model using 3D mapping to check how accurate my initial reconstruction was, from a shape-based perspective. These studies are common — that’s how validation is done nowadays.”

Smith has studied the relationship between shape-based accuracy and likeness extensively. “If we know that the currently available methods are accurate within two millimetres for 70% of the facial surface, that’s pretty good. But it doesn’t mean that the shape model is necessarily recognisable.”

Forensic art is divided into two broad categories, that of the identification and depiction of both living and the deceased. "For living persons, artists are usually involved with developing composites of persons of interest from eyewitness memory," she says. "For the dead, artists reconstruct facial appearance to assist investigators when other conventional methods of identification such as fingerprints, dental and DNA aren't available."

Increasingly, the importance of secondary identifiers, such as clothing and personal effects, are understood to have huge value in complex contexts, so Smith might need to also reconstruct objects. "It is in the heritage space, where a historical person may be shown wearing garments or with artefacts informed by the archaeological record, this contextual reconstruction informs our understanding of an unknown individual’s personhood. There are many contexts in which one might need to identify an unknown person, yet it is unknown whether they are alive or dead.

"Creating age-progression images, such as those you might do for abducted children or fugitives who have disappeared for various reasons is the least scientific method. In such cases, there is a lot of guesswork involved.

“There are certain things, like juvenile facial growth and development, for which you have data from the maxillofacial field [relating to the mouth, jaw, face, and neck] to refer to. But the specifics of a particular face? There are so many differences, even with twins. Lifestyle can have a huge impact on how they've aged. Age progressions may be the least scientifically supported with the forensic art suite of techniques, but they play a critical role prompting people to remember these events and people, and leads can be called in decades later. This is work of long duration.”

Artist, curator, and collaborator

“By nature, as an artist, you don’t think in silos. You’re used to working across boundaries all the time. It turns out this is very novel for people who normally operate in spaces where their roles and responsibilities are super delineated.

“In my research, I came across the fantastic concept of the ‘pracademic’ in public administration, referring to the practitioner-academic. A pracademic is someone who understands and can function in two or more distinct environments with very different functions, thereby acting as a critical vector of knowledge exchange between them.

“Such a person has active knowledge of and experience in both academic research and practice. A successful pracademic needs to be trusted to be able to move within and between both these spaces.”

Smith prefers to look at art, her own and that of others, through the lens of curatorship.

“I normally make installation environments, or curate exhibitions. I also extend my interest in curatorship to how I approach my own work. I put together lots of different things in order to explore unexpected relationships and the meaning or knowledge that may be created when unrelated things are made to connect, or familiar things come together in unexpected permutations.”

Smith’s online artwork Speaking Likeness, which is also an artist’s book, anthologises the diversity of her community of practice, from a global perspective. This work was recently featured in an exhibition in Norway and is currently on display in Slovenia.

Landing page of Speaking Likeness, an online artwork and anthology of narrative portraits of 18 forensic artists and imaging specialists from around the world. | Photo by Dr Kathryn Smith

Broadening perspectives, crossing boundaries

In the 1950s, the British scientist and writer CP Snow created two broad categories into which knowledge can be divided: knowledge created in the humanities, and that created in the natural sciences.

Snow suggested that these two kinds of knowledge are irreconcilable — a view that Smith is actively working against. In her opinion, forensic art shows anew that Snow’s supposed opposites, his two ‘cultures’ or ‘worlds’, depend on a distinction that lacks merit. And yet, she points out, it is not uncommon for a scientist to ask whether forensic art is at all systematic, or for an artist to question how creative forensic art can truly be.

“A lot of the disparities come from disciplinary conventions. Certain disciplinary conventions within science rub people in the humanities or arts up the wrong way, and vice versa,” Smith explains. This clash in the criteria used in various disciplines can mean that a given forensic facial depiction is completely successful in the forensic space but not appreciated as art, she says.

Yet, in working with forensic art as practice — something that has been theoretically neglected from a sociocultural, science, and technology perspective — Smith has brought people from various disciplines together. In doing so, many scientists have revised their assumptions that forensic art is “not scientific enough”, and artists altered their opinion of forensic art as “lacking creativity”.

How forensic art functions within a space filled with numerous systemic disparities is in itself a field of research for Smith, one where the quality of the questions is continually adapted and fine-tuned.

Forensic art at a crossroads

In various kinds of forensic work, one is confronted with someone who has lost their identity through whatever circumstance. In this regard, Smith explains: “You can’t ever fully reinstate personhood, obviously, but it remains an ambition. With forensic imaging, you are trying to identify an individual, you’re not trying to create a type of person. This is where assumptions based on legacies of data derived from physical anthropology, or ‘race science’, need very careful re-assessment.

“There is a move among more progressive practitioners in the fields of biological and forensic anthropology towards rethinking the concept of ‘ancestry’ or ‘population affinity’, and towards not including it in biological profiles based on analysis of skeletal morphology. Biological sex also needs some critical reassessment, given that it may not accord with our gender identity or presentation. Yet, the convention is to only think in binary terms, and the forms we use to report this data don’t offer a third space. Today, we understand more about the complexity of our genetic heritage through DNA, but both scientific cultures and popular perceptions need to catch up and get attuned to the full spectrum of what it is to be human, of which scientific analysis is only a part.”

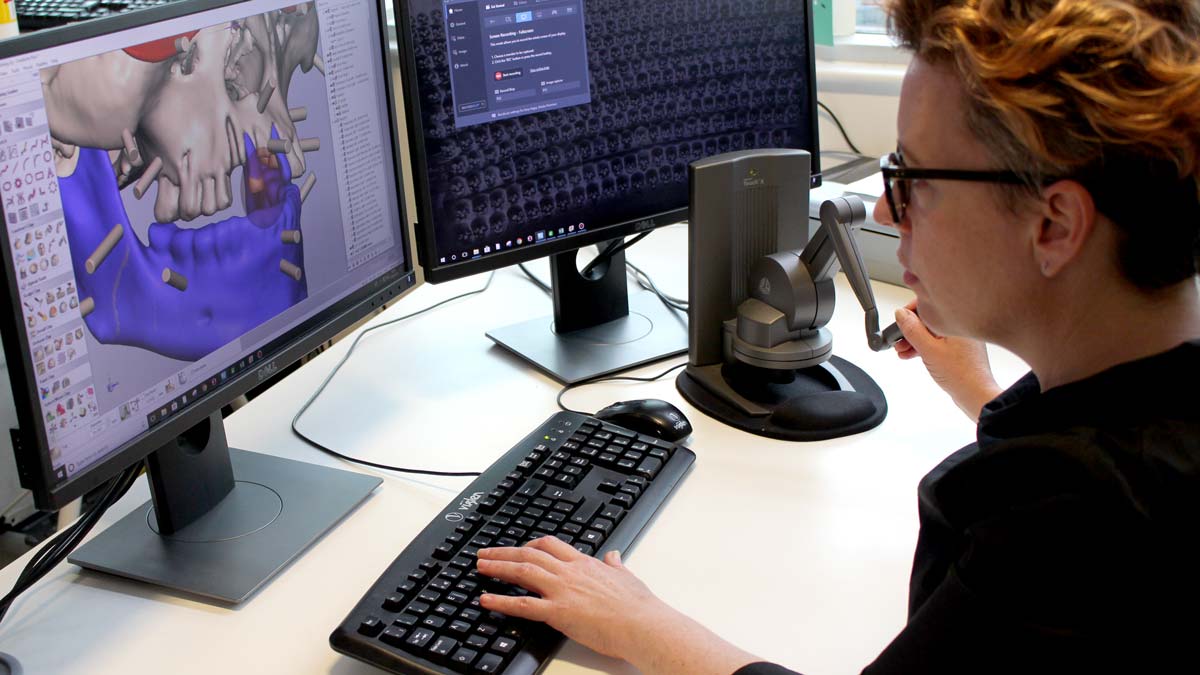

Dr Kathryn Smith utilises a haptic arm and advanced rendering technology to sculpt a three-dimensional model. | Photo by Anél Lewis

Technology, science, and art on equal footing

Technological and methodological advances enhance the scope and application of forensic art, which in turn enriches police work as well as heritage projects.

Smith explains that as a part of the Geomagic Freeform computerised sculpting system, she uses the Phantom Touch haptic arm. This articulated arm lets her control what she is doing on a screen, while feeling what she is doing as she sculpts. “The shape and contours of bone give us information, but that shape we understand through touch rather than sight. A lot of the information you have to get — grooves or depressions, or the bony bumps at the corner of an eye where the ligaments of the eyelid connect — is part of feature estimation methodology.

“It helps to have this haptic system for computer modelling because it offers a non-destructive way of working. It also means we never have to handle the actual specimen. For forensic cases, this is optimal to the preservation of the chain of evidence. The skull never needs to leave the lab. It is scanned, and then I get a 3D model of it. From an ethical perspective, I am not physically handling human remains. You would like to have the least amount of interaction possible with the actual remains, out of respect but also because it is no longer necessary.”

Learnings from AI

As advances in forensic art shape and broaden the field, Smith considers the implications of artificial intelligence (AI) as it is currently playing out: “For a long time, there’s been an interest in automating facial reconstruction. There was also the idea that if we can computerise it, then it is automatically more objective. However, the limitations of AI have since been quite well illustrated in the realm of facial recognition technologies.”

The problem can be explained in terms of these technologies’ current capabilities, she says. “It is essentially computer vision. You train your system on a data set. So, your system is only as good as the diversity of the data. And if you have a limited data set, you are going to get a limited output.”

Problems relating to AI output have already been highlighted in the art and research of, among others, Joy Buolamwini. “She has a Netflix documentary called Coded Bias and gave a TED Talk on the topic a couple of years ago. She realised the problem of the limitations of the dataset,” says Smith.

“The software couldn’t see her face until she put a white plastic mask over her [black] face — she is African American. She realised then that because people build these systems, they reflect our own biases, whether it is racism or whatever else. So, she’s an artist working in computer science to point out these flaws in the system.”

Forensic practice on two continents

Smith has looked at various international examples of how forensic art, both academically and in practice, might benefit people.

“A colleague at the National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children in the USA does facial reconstruction training workshops in different American institutions, using actual cases. He has worked with cases from the New York Medical Examiner’s Office and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The reconstructions are made public at the conclusion of each workshop and, more often than not, at least one or two of the depicted persons are recognised. So, they use a skills-transfer opportunity to simultaneously generate publicity around unidentified people. I want to replicate this in our context, but getting access to the data is the first challenge.”

Compared to ours, American laws tend to have a more relaxed interjurisdictional relationship when it comes to applying forensic art to unknown decedent cases, Smith says. “For instance, the medical examiner’s office could simply clear or make skulls available for such use. The forensic art is practised in a controlled context, led by an expert. In South Africa, however, there’s a lot of fear surrounding mortal remains.”

When asked about the impact of tighter regulation in South Africa, Smith says: “I think there’s so often a lack of understanding within the biomedical ethics space. One of the principles in clinical research is the anonymisation of patient data. In the forensic identification space, however, we are working with already anonymised people who must no longer remain anonymous. We are trying to identify them, which is a requirement in our Inquest Act, as well as a basic human right.

“Often, it can lead to a very interesting conversation as we are ultimately trying to answer the opposite question: How can we ‘undo’ anonymisation in death? Taking into account the greater good, you can often argue that the benefits outweigh the risks, which is essentially what ethics tries to balance.”

Incident Room, an installation exhibition by Dr Kathryn Smith, shown at Gallery AOP in Johannesburg in 2012. The project, which is still ongoing, explores the 1949 unsolved murder of Jacoba Schroeder, known as ‘Bubbles’. It formed part of the Bloody Book Week crime writing festival in Johannesburg before travelling to the Goodman Gallery in Cape Town. | Photo by Dr Kathryn Smith

Art that engages

“I’ve finally come to understand the connection between my forensic interest and my artistic or curatorial interests, which is that in order to properly care for bodies or objects, whether they’re human bodies or objects in a museum, you also have to understand and care for the systems that they pass through, or which are responsible for them. Proper care often involves doing work on these systems, and offering constructive interventions.

“Whether the context is that of the museum or the mortuary, objects and bodies have stories. I’m concerned with those people and things that have become somehow disconnected from their story.”

Interestingly, work in the forensic humanitarian action space may involve applying forensic (loosely, ‘for the law’) methods in a ‘counter-forensic’ way. “A counter-forensic approach entails using forensic methods against either current or previous governments or authorities, as a way to investigate unsolved criminal cases or the political wrongs of the past or the present.

“So much in forensic art is archivally driven, and the digital humanities have only begun to unlock it. Take heritage destruction in Syria or Afghanistan as an example. The 3D scanning of artefacts there may now be the only trace that exists of their heritage — the ghost of something, now made to exist differently in a new form, but at least there is a record.”

Broadening horizons

Smith has discussed advances in the field with Prof Sibusiso Moyo, Deputy Vice-Chancellor: Research, Innovation, and Postgraduate Studies at SU, given Moyo’s particular interest in how it could speak to work in the School for Data Science and Computational Thinking.

In this regard, Smith is also considering developing a database of synthetic faces that can be used to apply textures to models. “Otherwise, we have to photograph identifiable people to create these reference databases for feature shapes. The POPI Act, as well as research ethics around identifiable data, makes that quite complicated.

“A lot of the very sophisticated facial compositing software that is now available uses what is called ‘evolutionary algorithms’. When we see faces, we don’t encode them feature by feature. Our brains don’t work like that. We encode faces holistically. These software packages are corresponding more and more to our cognitive face processing and facial recall capacity.”

When using such software, Smith explains, one provides it with a very basic description of someone and then it brings up a gallery of similar-looking faces. “The two most like the person described to an officer are chosen, and these faces are then ‘bred’ together to create another array.

“If you iterate this process many times, it will produce a face very similar to the one someone has been describing. It is not just a case of adding eyes, a nose, and a mouth. The approach is holistic. Furthermore, the software has qualitative sliding scales that you can adjust for anger or health. You can also do animation because we don’t encode living faces as static and in frontal view, like in the bureaucratic convention of a passport photograph.”

Pearl Mamathuba, an academic researcher at VIZ.lab, an imaging laboratory based in SU’s Department of Visual Arts. Mamathuba and Dr Kathryn Smith recently presented their work at the 10th African Society of Forensic Medicine International Conference in Kigali.

A sense of urgency

Smith leaves little doubt that there is a dire need for forensic art skills internationally and also in South Africa. “This is only a back-of-the-envelope calculation because these statistics are not formally kept, but up to 10 000 people in our forensic medicolegal laboratories are left unidentified every year.”

There is a sense of urgency to her views on what needs to be done in terms of developing the field, given the societal implications we otherwise face.

“For one, we need to create jobs in the sector before we start offering any degree programmes. Right now, I am trying to generate as much exposure as possible by talking to academic and popular audiences and looking at ways we can build on existing research networks and projects locally, internationally, and in Africa.

“I recently returned from the 10th African Society of Forensic Medicine International Conference in Kigali. It was an extraordinary meeting, and our contributions were so warmly and well received. There is so much scope for developing forensic facial imaging in neighbouring African countries with some forensic infrastructure, especially in parallel with the extraordinary work of the International Committee of the Red Cross and the new African Centre for Medicolegal Systems.”

Ultimately, Smith sees connecting with and creating open lines of communication between various roleplayers as the first and most important task in the development of the field.

“Stakeholders across the board, from top SAPS officials to forensic officers within FPS who deal with the public, to social justice advocates, established academics, students interested in career pathways in the forensic sciences or art, and everything in between, need to be made aware of all that is at stake if we don’t pay attention to the unidentified bodies in our mortuaries.”

She quotes the statesman William Gladstone: “Show me the manner in which a nation cares for its dead, and I will measure with mathematical exactness the tender mercies of its people, their respect for the laws of the land, and their loyalty to high ideals.”

The research initiatives reported on above are geared towards addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals numbers 9 and 16 and goal numbers 2 and 11 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Useful links

Forensic facial imaging laboratory promotes interdisciplinarity

Western Cape Cold Case Consortium

Dundee’s Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification

10th African Society of Forensic Medicine International Conference

Forensiese kunstenaar: ‘Dit het alles in ’n lykshuis begin'

Twitter: @serialworks and @MatiesResearch