Recovering subterranean poetry and literature

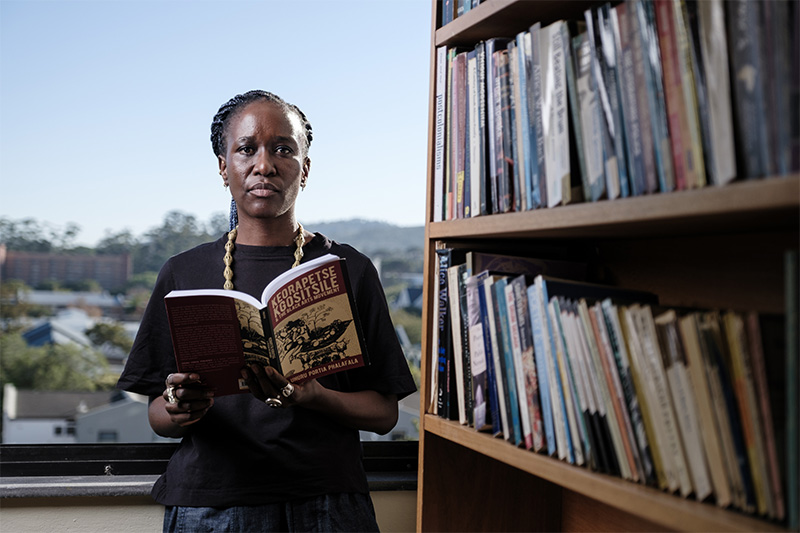

“My research areas are the literatures and cultures of the African continent and throughout the world where Africans are dispersed or displaced through slavery, colonialism, and forced migration,” says senior lecturer in the Department of English, Dr Uhuru Portia Phalafala.

Her focus on these research areas started with her master’s study at Wits University and her PhD study at the University of Cape Town. Today, she holds a National Research Foundation Y1-rating.

“Through interviews with writers and poets, and searches for lost literature I am retrieving some of the histories of African people who have been dispersed, such as South African anti-apartheid activists who lived in exile during apartheid,” she explains. “The stories and writings are biographical studies of black life, including the work of black women activists whose writing, for the most part, is glaringly absent and which importantly contributes to the gaps of knowledge in the archives and libraries.”

Recovering, retrieving, healing

Much of Phalafala’s work is structured under the research title ‘Recovering subterranean archives’. “It’s my lifework,” she says. “It has to do with recovery as a form of retrieving and healing. We say someone is ‘recovering’ when they are healing, and the act of recovering the histories of people who have been marginalised and dispossessed is a form of healing.”

Phalafala explains the subterranean element of her work as referring to the ‘underground’ (both metaphorical and real), as the stories she unearths were previously lost, buried, and unknown. Also, much black literature, music, and intellectuality was circulated underground during periods like apartheid when it was banned.

The poetry of ANC women in exile

An example of unearthed writings is Phalafala’s republication of an anthology of poetry written by ANC women in exile in Angolan military training camps in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The anthology was first published in 1981 by the late South African cultural activist, poet, and politician Lindiwe Mabuza, under the title Malibongwe! ANC Women: Poetry Is Their Weapon.

“This anthology subsequently went into obscurity and I learnt about it through the late poet Keorapetse Kgositsile, who had a copy of it. During apartheid, he was in exile mainly in New York. He became a mentor of mine and the subject of my PhD research,” Phalafala explains.

She republished the anthology through uHlanga in 2020, under the title Malibongwe: Poems From the Struggle by ANC Women. The publication formed part of a Mellon Foundation-funded project on recovering subterranean archives, of which Phalafala was the principal investigator.

Her most recent book, published in 2024 by James Currey/Boydell & Brewer and Wits University Press, is titled Keorapetse Kgositsile & the Black Arts Movement: Poetics of Possibility. She also co-edited The Collected Poetry of Keorapetse Kgositsile, published by Nebraska University Press in 2023.

The cover of Phalafala's most recent book, titled Keorapetse Kgositsile & the Black Arts Movement: Poetics of possibility.

Dr Uhuru Portia Phalafala | Photo by Reza Khoza

The female voice in black consciousness

“What is critical about the Malibongwe research is that, wherever possible, it is connected to people who are still alive. Several of the contributors attended the 2020 book launch, including the former speaker of the National Assembly, Baleka Mbete,” says Phalafala.

The contributing women poets had not laid eyes on the anthology for years and immediately engaged in the “very necessary” conversation about what it meant to be a woman in the struggle, she notes. “Through these discussions, they too moved through the journey of healing and restoration.”

Phalafala explains that, during apartheid, many women left South Africa from as young as 16 to be trained in military camps in Angola and other countries. “They spoke about their good, bad, and heart-breaking experiences as revolutionaries in exile. The poems hold potent content, such as what it feels like to be pregnant and carrying an AK47 or breastfeeding in a military training camp,” she explains. “They spoke about their dreams of a free South Africa and the textures of these dreams are very different to those of male anti-apartheid revolutionaries.”

Through her work, Phalafala has given the female voice a significant place in the body of black consciousness poetry, which was previously skewed in the direction of male poets and had a very masculine aspect. “The nuanced textures that emerge from the female revolutionary poets and writers are not just about bombs, bullets, and boots —they focus on the human questions of what it means to be a human living under oppression, and how the human is restructured in regimes of violence.”

Drawing on jazz

In addition to the printed work as a source of knowledge, Phalafala is also exploring the African tradition of conveying knowledges and philosophies through oral and performative cultures. “This requires stepping outside of the archives and interviewing the living repositories of our histories and philosophies. My book on Keorapetse Kgositsile draws on these methodologies: interviews with him and his contemporaries, [analyses of] his poetry (which enshrines African indigenous knowledge systems and wisdoms), as well as the use of jazz as a method of tracing that which lies on the outside of the colonial library,” she explains.

“It reveals that the history of black intellectual production is very communal, and just like jazz, it is about the ensemble. If we look at the histories of displacement, black life was thrown into crisis — a state of emergency that subsequently produced a state of emergence — and this required improvisation as a way of life, hence my reference to jazz improvisation as paradigmatic of black life.”

Phalafala is also researching the relationship between black South Africans and African Americans in the 20th century and how the civil rights movements and black consciousness, black power, and black activism in South Africa and the United States related to one another. “The historical records show the impact of African American politics, culture, and education on black South Africans, but I look at how black South Africans impacted African Americans, drawing on jazz as a modality to capture oral/aural cultures — performative and literary cultures co-created, exchanged, and emulated in dynamic, reciprocal relationships,” says Phalafala, who teaches a course titled ‘Thinking Through Jazz’ to her third-year students.

“It’s a different approach to thinking through history. Instead of exploring history through books or the colonial library, we approach it through performance, through the sonic and jazz, the choral — by listening to history using your ears, such as in Hugh Masekela’s ‘Stimela’,” she explains. “It offers insight into the social theory of racial capitalism and the makings of global capitalism, which is inextricably intertwined with the makings of race. There has to be a dehumanised ‘other’ to work on the mines, and songs like ‘Stimela’ are prisms to learn what it feels like for the miner to be removed from their ancestral land, to stay in male hostels, what food they ate, what their inner worlds looked like, what it felt like to spend your life underground, be treated as sub-human, and only go home for two weeks a year.”

Music offers a different approach to thinking about history.

From the women they learnt the culture of love

Phalafala adds that, as was the case for many South Africans, Keorapetse Kgositsile was raised by his grandmother and mother “precisely because of the racial capitalist mining industrial complex”. She says it was from the women that children learnt cultures of love — love for the self, love for family, and love for community. This love also provided the fuel to resist the hate, domination, coercion, and separatism that characterised the cultures of apartheid and colonialism.

“I argue for the home as a site of resistance — that the cultural worlds transmitted by women become the basis for fashioning black radicalism. As the late author and educator Bell Hooks said: In white supremacist societies you could not learn to respect and love yourself from the outside; it was in the home that you learnt to love yourself. And that love, dignity, and self-respect is the seed of resistance. This is what I call the ‘matriarchive’, whose continuously productive charge forms and informs a transnational black feminism.”

An absent black male and father

Phalafala raises these issues in her poetry anthology, Mine Mine Mine (University of Nebraska Press, 2023). “I look at the core relationship between the mining industrial complex and the extraction of the black male from families, communities, and societies. These phenomena inaugurated new social structures from those of black life before predatory capitalism, and have contributed to many social ills, including the scourge of gender-based violence today,” she explains. “Working underground, with their humanity continually being undermined and diminished, something happens to the men psychologically: They shut themselves off, necessarily, in order not to feel the ongoing attack on who and what they are. Some eventually become prone to addictions, and/or desert their families. Young boys grow up without male role models and they, in turn, don’t know how to be fathers.”

The cover of Phalafala's most recent poetry anthology, Mine Mine Mine.

Black life and the natural environment

Phalafala’s latest work is about investigating black geographies and critical ecological studies from the perspective of black life, which has always been entangled with the natural environment. “The very understanding of the self and who we are and how we relate to the living environment is part of black life,” she explains. “Our languages and our full names (not the names truncated by colonial administrators but our clan or praise names) point to kinship with animals, rivers, mountains, and natural areas. We have totems that pronounce our relationship with the animal kingdom.

“Black geography has everything to do with environmental studies and the concern with the environmental catastrophes we are witnessing. Environmental research as a field of study tends to invalidate or ignore the fact that the unsustainable extraction of the earth in our country, and in many others, is not achievable without the extraction of the black body. They are inextricably intertwined and I draw on this to intervene in environmental and ecological studies today by tracing their roots in colonialism and racialism.”

Dr Uhuru Portia Phalafala

Photo by Stefan Els

Written by Heather Dugmore

Useful links

“The most hidden open secret”: Interview with Uhuru Phalafala on Mine Mine Mine

Sound thinking: Black women’s acoustemologies as resistance

Mine Mine Mine by Uhuru Phalafala

Dr Phalafala talks about her book Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement

LOSS | LAND | LINEAGE | LANGUAGE | LOVE - Mine Mine Mine

X: @MatiesResearch and @StellenboschUni