Enlarging the gaze on infant mental health

Ufrieda Ho

Illustration by Roulé le Roux

Milk teeth peeping through and those first wobbly steps are typical milestones that parents and caregivers look out for in infants. But researchers say there’s more to take note of and good reasons for it too, especially when it comes to mental health benefits.

The first 1 000 days of life — from conception to about two years of age — are critical in a child’s development. During this time, the brain’s ‘wiring’ develops at a staggeringly rapid rate: First, nerve cells (or neurons) migrate and grow to become the structures that form synapses; next, the synapses connect to form neural pathways and circuits.

Researchers have long known that this so-called ‘golden period’ offers an ideal window for increased support and intervention toward optimal fetus and infant development. Nutrition and stimulation have been critical to supporting brain development for a stronger metabolism and immune system. But as researchers delve deeper into the complexity of neural pathway development, they are homing in on mental health. Thus far, this research has yielded a wide range of practices that pregnant couples, parents, caregivers, and healthcare professionals should be aware of.

The call for early intervention is based on a growing body of research that shows that the architecture of certain mental health disorders seen in adults is cemented long before adulthood.

Dr Berna Gerber (on the left), a senior lecturer in the Division at Speech-, Language- and Hearing Therapy and Dr Anusha Lachman, a senior lecturer in psychiatry and head of the clinical child psychiatry unit at Tygerberg Hospital. | Photo by Stefan Els

A starting block

Stellenbosch University (SU) recently launched the Early Intervention and Child Mental Health ‘public square’. The latter recognises the urgency of responding proactively and innovatively to this new information. This square was built on the concept of intentionally connecting researchers to promote transdisciplinary research and collaboration. It also brings together collaborators outside of the academic sphere, including policy experts, activists, civil society actors, and NGOs.

Dr Berna Gerber is a co-lead of this health sciences public square. She says, “The square is about moving outside of one’s own discipline into a shared space and also about addressing real-world problems and making a difference.”

The square aims for research to translate into impact, especially in the form of support for children and persons with disabilities (including those who have or are at risk of developing mental health issues). In addition, it hopes to raise the call for interventions that may help prevent certain mental health and developmental problems as an infant grows.

“Our public square is directed at the health and well-being of young children. It also considers what happens during pregnancy, and even before pregnancy, because so many things in one’s life depend on factors like what was going on in your parents’ lives before you were born — even before you were conceived,” says Gerber.

Her work in the Division of Speech-Language and Hearing Therapy examines the connection between learning and communication in infants, and how this affects them as they grow. She also focuses on supporting mothers of preterm babies, and on early communication development in such infants.

She says: “We know that children who may be at risk of mental health difficulties may also be at risk of other developmental delays, including delays in growth, learning, and communication, and vice versa.”

Much is still unknown, however, about the effect of infants’ experiences and emotions on their development. To complicate the matter, although many find it obvious to think of infants as “feeling, thinking, experiencing, and sensitive” young humans, it simply isn’t a universal concept, Gerber says. This means that the way that people interact with infants doesn’t follow a single standardised approach.

Gerber illustrates this point by pointing out that some parents believe a child should not be spoken to in so-called ‘baby talk’ or, in certain cultures, spoken to at all. Also, not so long ago, it was considered acceptable for corporal punishment to play a role in the disciplining of children. And, she says, until quite recently, infant pain was not a serious consideration in medical care or research.

“I think, though, that awareness is shifting; societies are evolving. But we really are just at the starting point when it comes to understanding how important it is to spotlight the needs of infants, including their mental health needs,” she says.

The point, however, is to start, Gerber says. According to her own research, parents and caregivers should be encouraged to realise the benefits of being fully present when spending time with a baby or small child: “We use programmes that teach caregivers to ‘observe, wait, and listen’ or ‘watch, wait, and wonder’ when they are interacting with a baby. Of course, we are competing against things like screen time and being in a perpetual rush, but nothing can make up for attention, for reciprocity, or for nurturing between a baby and its primary caregiver. Equally important is ensuring that caregivers are supported and that their most important needs are met.”

Prof Heather Brookes is an associate professor in the Department of General Linguistics and head of SADiLaR’s CLDN, housed at SU. She specialises in multimodal (verbal and gestural) communication. | Photo by Stefan Els

Local data for local good

The public square approach furthermore emphasises the need to advance research and the collection of data that are relevant to and reflective of South African contexts.

Prof Heather Brookes, a member of the public square, heads the Child Language Development Node (CLDN) of the South African Centre for Digital Language Resources (SADiLaR), housed at SU. Her current research shows just how necessary more nuanced research and data are if we want to understand the interaction between cognition, communication, and behaviour within the first days of life.

What we know, Brookes explains, is that there is an interplay between language development and cognitive development. As such, language development is a predictor of things such as behavioural development, success at school, and mental health challenges.

To this end, Brookes and a team of other scientists have adapted a developmental assessment tool to establish gesturing, communication, and early word formation norms for South Africa’s 11 official spoken languages. The South African Communicative Development Inventories (SA-CDIs) project gathers data on children between the ages of 8 and 30 months through questionnaires completed by parents and primary caregivers. The large data set will be developed into a comprehensive inventory that promises to be a game changer for the field, says Brookes.

“Knowing what typical development in our languages looks like will mean early detection and intervention in tackling language delay that might otherwise result in learning and mental health challenges further down the line.”

In developing this instrument, the researchers were deliberate in enrolling parents from both rural and urban households to report on their children’s first gestures, words, and sentences. Brookes says this is necessary to ensure that the developmental tool takes into account South Africa’s socioculturally and geographically diverse, multilingual society.

The project is six years in the making and is now aimed at collecting data from 28 000 households that represent all 11 languages. Globally, it will be one of the largest surveys of child language development yet. As huge and seemingly insurmountable as the task may appear, Brookes says, it is essential — relying on western tests and norms in our African context poses inherent problems.

“Using a British measuring tool, for instance, could lead to South African children being underdiagnosed or overdiagnosed because of the tool not factoring in our linguistic and cultural differences,” she explains.

One of the aims of the project is to create a free and anonymised online child language database and assessment checklist, in collaboration with SADiLaR. There are also plans to develop the tool as an app so that it can reach more households via their electronic devices.

Prof Xanthe Hunt, the mental health lead at the Africa Health Research Institute and a part of the Early Intervention and Child Mental Health 'public square'. | Photo by Samora Chapman

Academic expertise gets back to basics

Prof Xanthe Hunt is a faculty member in SU’s Department of Global Health. She is also the mental health lead at the Africa Health Research Institute, and a part of the Early Intervention and Child Mental Health public square. Her work focuses on ways to strengthen mental health frameworks and to ensure more appropriate interventions toward systemic changes that will prevent mental health care — especially that for adolescents — being pushed to the margins by an overburdened health care system.

For Hunt, the public square offers an opportunity for a collective of specialists to reflect more deeply on how to translate their individual expertise into maximum impact. Hunt believes it begins with acknowledging the blind spots within academia.

Young researchers and academics are encouraged to quickly find a specialisation in order to advance their careers and gain peer recognition, Hunt says. The pursuit of specialisation can, however, result in careers being “siloed”, she argues. This is why she believes generalist scientists can play a critical role in bridging discrepant pieces of research.

It’s a generalist approach, she says, that will allow people to see a much larger picture and tie together seemingly disparate strands of information. Understanding different perspectives, she believes, will reveal to researchers that mental health issues are not separate from, for instance, socioeconomic and environmental factors, or generational trauma. Growing up in communities that have fallen through the cracks and suffer high degrees of violence, crime, and drug misuse, for example, can significantly impact mental health. Even babies are affected by living in environments marked by persistent fear and anxiety.

Hunt says: “We have to recognise that ecosystem change is necessary in the fields of child development and public health [research] and this does require generalists, or at least people with a broad enough perspective to foster interdisciplinarity.”

She adds that inculcating a generalist approach means science and research can take up more seats at different tables. This is essential to growing awareness, strengthening advocacy, and affecting change among a range of actors from government officials, policymakers, civil society members, and community health workers, to everyday moms and dads.

Understanding individual, community and household needs, Hunt says, enables the implementation of interventions that are more relatable and therefore more impactful than they would otherwise have been.

She argues that it’s important for programmes and interventions to “meet people where they are and not make assumptions”. For instance, she says, it’s important to know where people spend most of their day and to then reach them in those locations, or to know whether a certain community is more collectivist or more individualistic in its approach to child-raising and to then tailor programmes accordingly.

“Simple things like accounting for women’s work in under-resourced communities can change the way we work with caregivers and create safer spaces for children.

“Making sustainable change largely comes from pulling back to things like changing labour regulations and more directed resource allocation for low-resourced communities,” Hunt says.

Better advocating for infants begins with intentionality, and also humility — it requires understanding that scientific knowledge is not the only form of knowledge, Hunt believes.

“Tapping into diverse ways of knowing can foster new insights, and ultimately drive transformative change,” she says.

It also requires humility to understand that, for many, reality is shaped by South Africa’s grossly unequal society. She says: “We need to understand that someone who struggles with emotional regulation as an adult may not have had the opportunity for co-regulation in a responsive relationship with their caregiver when they were an infant. We must also realise that to interrupt intergenerational cycles of hurt and harm, we need to focus on the parent-child dyad.”

Child and adolescent mental health: Building an ecosystem of support

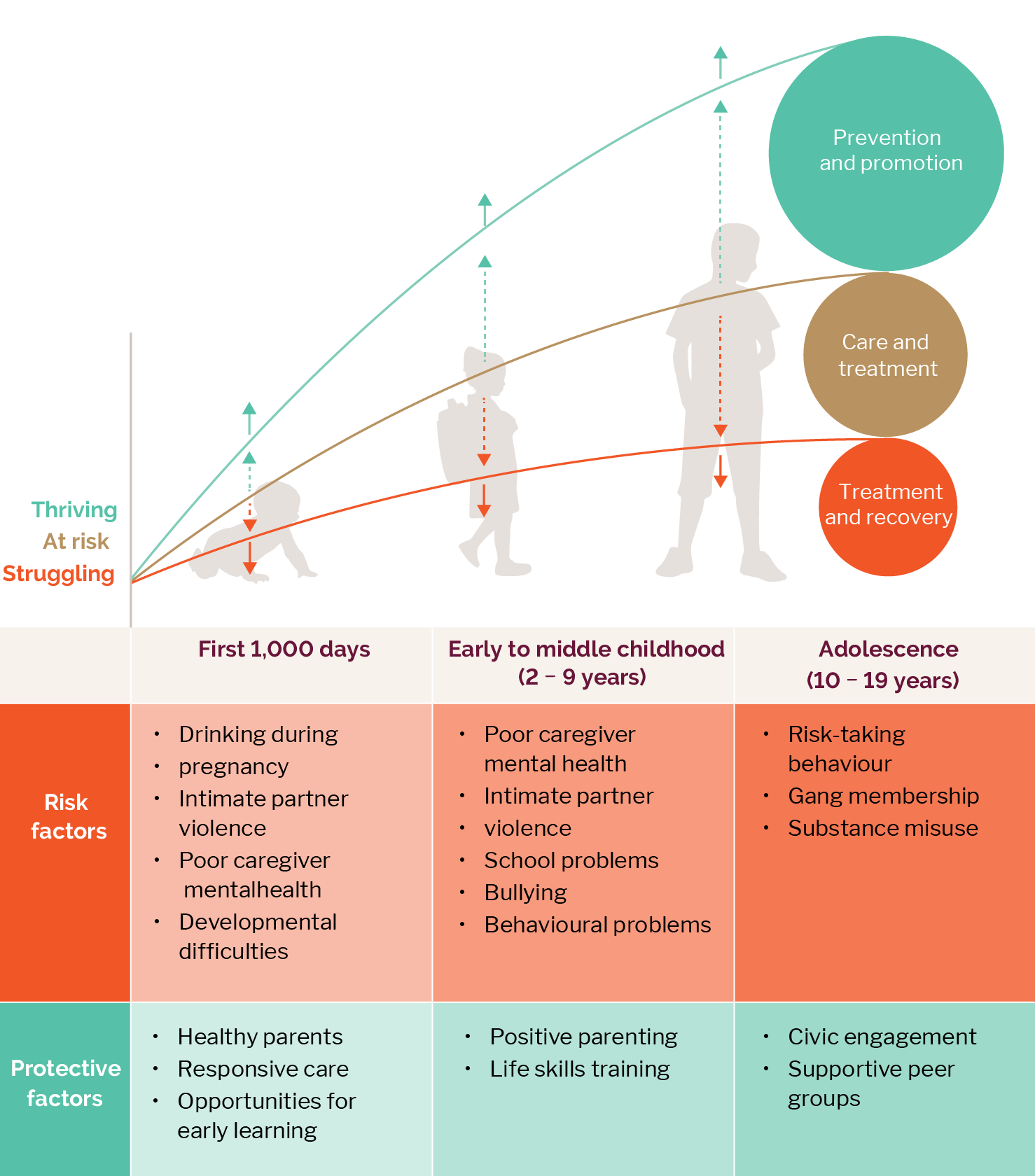

A life-course approach

• The early years of life are critical in determining adolescent and adult mental health outcomes.

• Timely investment in mental health — i.e., through addressing the causes rather than the consequences of ill health — is both essential and cost-effective. This demands early and sustained intervention, starting even before conception.

Environment matters

• Mental health is shaped in powerful ways by children’s relationships and living conditions.

• Poverty, violence and discrimination compromise the development and mental health of South Africa’s children and increase their risk of developing anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

• These risk factors frequently co-occur, with many children facing multiple adversities that accumulate across the life course.

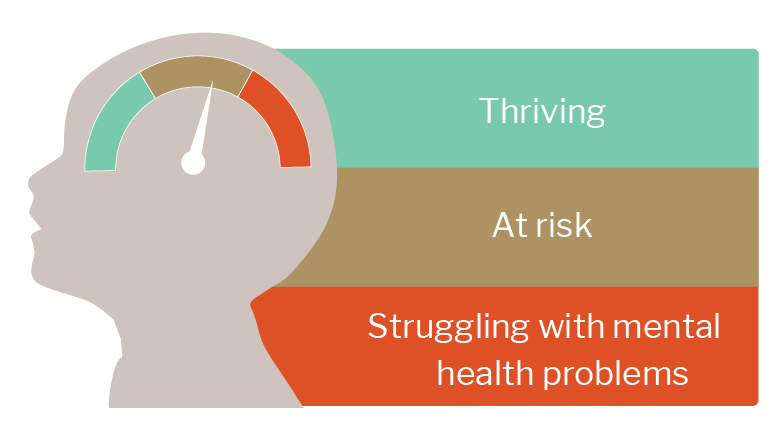

A continuum of mental health

- Children may move along a continuum of mental health in response to changing life circumstances.

- Most children are mentally healthy and have the necessary confidence to handle life’s challenges. That said, all children may experience periods of worry or distress due to a variety of possible difficulties, ranging from starting at a new school or the pressure of exams to the loss of a loved one.

- Children’s mental health becomes jeopardised when their feelings of anxiety and distress start to interfere with their relationships, school work, or everyday routines. With the necessary support, however, they may overcome the challenges they face and return to a state of good mental health.

- About 1 in 10 children will develop a diagnosable mental disorder and/or psychosocial disability that will require professional support and/or psychiatric care.

This graphic highlights how early experiences of adversity can ripple out across an individual’s lifecourse and across generations, at great cost to society. | South African Child Gauge 2021/2022

Dr Anusha Lachman | Photo by Stefan Els

Growing the knowledge network

Dr Anusha Lachman is a senior lecturer in psychiatry and head of the clinical child psychiatry unit at Tygerberg Hospital. She has been involved in implementing a graduate programme focused on infant mental health through an interdisciplinary training infrastructure. The first cohort of master’s students graduated in 2017 and included psychologists, nurses, dieticians, and doctors. To date, 13 students have graduated from the programme.

As the programme grew, limited supervision capacity meant that not all the applicants could be accommodated. Lachman says the demand has been encouraging, but also shows how much more ground needs to be covered if infant mental health is to become a part of the mainstream health care framework, and if the growing demand is to be met.

Fortunately, Lachman says, the challenge of limited capacity to reach more students presented an opportunity for creative problem solving through different interventions.

The first enlisted the help of the MPhil graduates. “By using our students, we were able to run outreach workshops that served to upskill clinicians on the ground, and to support their education and training.

“Having insufficient capacity also forced us to think creatively around ways to make the information and the field in general more accessible to clinicians, allied health professionals, and educators. This resulted in the creation of our first online short course on infant mental health, which was launched in 2022 and has been offered twice since,” Lachman says.

The online platform, which continues to grow in popularity, has made training available to students beyond South Africa’s borders. “This has been a huge step for us toward making infant mental health in Africa more accessible.”

Lachman adds that having a range of options — from short courses and virtual courses to full master’s programmes — has meant adapting better to the different ways that people want to or are able to learn.

“We need increased public messaging and awareness that infants are a product of their environments and of the support of their caregivers. If we expect infants to do well and thrive, we need to make sure their environments are safe and supportive, and that caregivers are well, both mentally and physically. For that to happen, we must be open to talking about social determinants of mental health (poverty, violence, substance abuse, food insecurity, untreated mental illness, stigma, etc.), and we must screen [for mental health issues] early.”

Lachman says she’s encouraged by the fact that the public square has already taken solid strides forward, especially in terms of answering pressing questions in different ways, and in taking bolder approaches to training, advocacy, and research.

“We have been awarded an important opportunity to advance infant mental health and early childhood interventions through the public square, and we must persevere with this work,” she says.

The square may still be taking baby steps toward its ambitions, but each one of them is moving the initiative steadfastly forward.

Mental health matters

- Global data shows that one in every seven children between the ages of 10 and 19 years suffers from a mental disorder. This accounts for 13% of the total burden of disease in this age group.

- Many different factors may impact a child’s mental health, including low birth weight, maternal malnutrition and mental health issues, and adolescent parenthood. Globally, approximately 15% of children are born at a low birth weight, and a similar percentage of girls become mothers before the age of 18.

- Half of all mental health conditions have their onset by age 14, yet most cases remain unidentified and untreated.

- The World Health Organization warns that failure to address adolescent mental health conditions means teenagers can carry the burden into adulthood, leading to an impairment of both physical and mental health, “and limiting opportunities to lead fulfilling lives as adults”.

- Poverty negatively affects a child’s physical and socio-emotional development. Conversely, mental health conditions can lead to poverty. Globally, nearly 20% of children younger than five years live in extreme poverty.

- Mental health exists on a continuum, with individuals experiencing different levels of difficulty and distress, and being socially and clinically affected by these challenges to varying extents.

- As a basic human right, mental health is crucial to personal, community, and socioeconomic development. This renders it important in achieving global objectives such as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

-

Across the world, in the age group 15–29 years, suicide is the fourth most prominent cause of death.

On home ground

- There are serious gaps in psychiatry regarding treatment, prevention and care for children and adolescents in South Africa.

- Despite South Africa currently undergoing a mental health crisis, there are still fewer than 40 registered child psychiatrists in the country.

- One child psychiatrist is trained only every two years at one of only four local universities.

- Over the last three years, South Africa gained three child psychiatrists.

The research initiatives reported on above are geared toward addressing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals number 3 and goals number 1, 2, 3, and 18 of the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Useful links

SU’s Department of General Linguistics

SU’s Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

Child Language Development Node (CLDN)

South African Centre for Digital Language Resources (SADiLaR)

SU’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences

Africa Health Research Institute

Focus on children, urges president of SA Society of Psychiatrists

More than just words — developing tools to measure early language development

The South African Early Childhood Review 2024

X (formerly Twitter): @bernagerber; @xanthehunt; @SUArtsSocialSci; @MatiesResearch and @StellenboschUni