Uhuru Phalafala

I have been teaching a course on Black Consciousness poetry in the universities for close to seven years and have been nagged by the silence and absence of women in that unfolding radical moment. For about five years now, every August, the month that in South Africa marks women’s month, an image of Minister Lindiwe Zulu from the 1980s circulates on social media. She looks away from the book in her hands to confront us with a direct gaze into the camera, with a Kalashnikov resting easily next to her hip.

The image represents a battle fought with both ideological and military warfare; what the Cold War machine would have called soft power (culture) and hard power (artillery). That image of a female guerilla looks as provocative as it does organic: the people closest to the pain should be closest to power, driving and informing the contours and contents of a revolution. The country’s history dictated their constitution: black, hypermasculine, clandestine, and Molotov-wielding. The battle lines were drawn along racial lines exclusively.

When the white oligarchy peddled fear in their white subjects through the image of swart gevaar what they conjured was not black women. But history absolves them today. Their variegated voices erased by national liberation narratives shall be heard. Black women were at the frontlines and in the underground confronted with a distinctive battle, against the white supremacist machine impaling their families and communities, and often against hetero-patriarchy within their ranks, which came to symbolise the notion of nation. To be a female guerrilla was to submit oneself to multiple warfares. They were in the trenches of Tanzania, Angola, and Mozambique as fighters, teachers, students, guerillas, and nurses.

Lindiwe Mabuza championed the Malibongwe book project. She drafted a letter to the head of the ANC’s women’s section, Florence Maphosho, to propose the idea. Mabuza asked Maphosho to disseminate the letter to all the women in the camps, offices of the ANC around the world, and at the nascent Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College (Somafco). There was great interest as hand-written submissions from all the camps began to arrive in Lusaka. Angela Dladla-Sangweni, Mabuza’s sister in law, helped to type all the poems. Mabuza had the full manuscript by the time she went to Sweden in 1979. At the time she was also at the helm of fundraising to construct the new Somafco, and had arranged for artists within the Angola camps to contribute drawings and illustrations which she could sell to advance that cause.

She sold the originals to several Scandinavian countries as she was ANC’s official representative to the entire Nordic region, but kept copies for inclusion in the first edition of Malibongwe’s English version. She approached then-secretary at the Center for International Solidarity in Sweden, Bjorn Andreasson, to help raise funds for the publication of the poetry anthology. While this was in the pipelines, the German translation became the first to be published by Munich-based Weltkreis-Verlag in 1980. Translated by Elizabeth Thompson and Peter Schütt, this edition was expedited by the ambassador of the ANC Mission for the Federal Republic of Germany and Austria, Tony Seedat, and wife, Dr. Aziza Seedat. They had already been in liaison with the publisher in 1980, who was at the time publishing another South African poetry collection by Keorapetse Kgositsile titled Herzspeuren/Heartprints (1980), at the behest of Aziza Seedat.

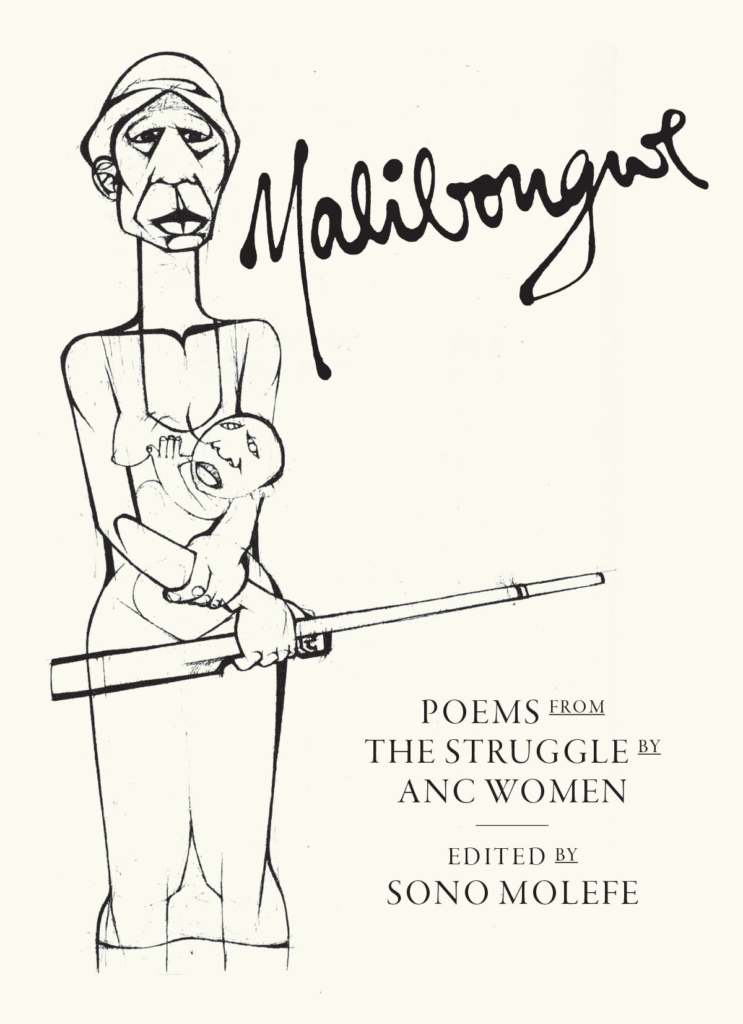

In 1981 Bengt Save Soderbergh of the Centre for International Solidarity of the Labour Organization in Sweden had taken over oversee the full publication process, and published 2000 English language copies. Most copies were distributed by ANC officials around the world, at the discretion of the party’s chief representatives. At subsequent ANC meetings and rallies people were reading the women’s poetry. Meanwhile Soderberg approved funding for Erik Stinus to translate the anthology into Swedish and Danish, published in 1982 by the anti-apartheid solidarity group Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke. Later in the decade (date unknown) the Finnish Peace Committee had a smaller batch of the anthology translated into Finnish and published in Helsinki. The demand for Malibongwe’s German edition resulted in the second edition being reprinted in 1987, this time carrying five illustrations by ANC member and eminent abstract expressionist Dumile Feni, one emblazoned on the cover. This was inspired by the illustration and design of Kgositsile’s collection. We carry the spirit of collaboration in this edition through the awe inspiring Feni masterpiece. These networks of international solidarity and support attest to the power of culture in fostering strong political tools for revolution.

Some of the poets in this anthology have used pseudonyms as they were underground. The following contributors have since passed on: Belinda Martins, Thuli Kubeka, Phumzile Zulu, and Mpho Segomotso Dombo. May their revolutionary souls rest in peace.