14 January 2021

By François van Schalkwyk, Jaco Blanckenberg, Nico Cloete, Peter Maassen and Johann Mouton

African scientists’ share of the world’s publications has been increasing and more of the research published by scientists from the continent is being cited, but more regular, reliable and comprehensive data on research universities in Africa is needed to ensure that imminent decisions related to investing in the continent’s universities are well-directed.

Knowledge collaboration between high-income countries and countries in Africa has been dominated traditionally by primary education. Collaboration in the areas of higher education and research was seen as a ‘luxury activity’ and has, in essence, been limited to educational and administrative capacity-building and short-term applied research and consultancy projects, as well as scholarships for African students to study at universities in the North.

Collaboration was also primarily operationalised as development aid rather than as sustainable and equitable partnerships.

From 2000, starting with the declaration by the late former United Nations secretary-general Kofi Annan that “the university must become a primary tool for Africa’s development in the new century”, there has been a slow but persistent change, albeit with more promises than deliverables, towards strengthening the research capacity of universities in Africa.

There has also been greater support for and interest in developing a better understanding of the research landscape in Africa.

A major project in this regard was the Higher Education Research and Advocacy Network in Africa (HERANA). The HERANA project had two main features: it identified eight universities in Sub-Saharan Africa as research universities and, over a 10-year-period, it collected data on the research performance of the participating universities. The project ended with the formation of the African Research Universities Alliance (ARUA), a network of 16 research universities.

Since its inception, ARUA has launched a UK-funded partnership focusing on supporting 13 centres of excellence. Currently, ARUA is in discussion with the Guild of European Research-Intensive Universities and the European Union about establishing clusters of excellence between the 38 member universities of the two organisations.

No reliable data for development collaboration

Growing investments in university research and a lack of regular, reliable and comprehensive data on their research activities can easily lead to misinterpretations of research trends, as well as a limited understanding of what kind of investments are needed and the outcomes the investments can be expected to produce.

Consequently, focused investments, combined with the production and use of data, are a crucial condition for African universities to be able to enhance their capacity to operate at the research frontier in some areas, to produce knowledge of relevance for their societies, and to be able to absorb and adopt advanced technologies.

In the remainder of this article, we seek to provide a selection of the currently available data to correct and inform perceptions about the scientific research landscape in Africa. We also seek to draw attention to the data gaps that exist, and which preclude a more fine-grained understanding of the continent’s scientific research productivity and potential.

A note on the data in this article

The bibliometric analysis presented below is based on the Web of Science (WoS) metadata licensed to the Centre for Research on Evaluation, Science and Technology (CREST) at Stellenbosch University by Clarivate Analytics. The analysis is based only on articles and reviews that are indexed in the Web of Science. Research that is published in local journals and that are not indexed in the Web of Science cannot be included, and points to the need for continued efforts to broaden the representativity of the Web of Science.

Africa science rising

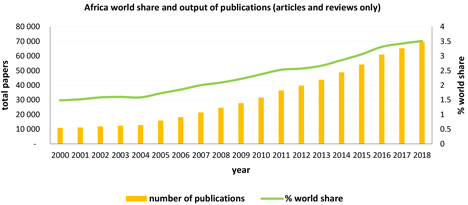

Figure 1 shows that the African continent has increased its contribution to global science in the form of research publications from nearly 11 000 publications in 2000 to nearly 70 000 in 2018. A part of this growth is attributable to the increase in journals covered by the Web of Science as the global scientific output increases, especially in regions such as Asia, where considerable investments in science have been made in recent decades. Therefore, it is more informative to look at Africa’s share of the world’s publications, also shown on Figure 1. This grew from 1.5% to 3.5% in the 19-year period.

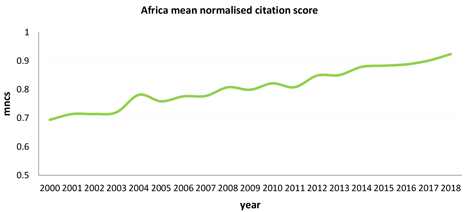

As a measure of academic impact, we focus on citations and use the mean normalised citation score (mncs). A higher score reflects greater academic impact with a score between 0.8 and 1.2 being considered average. Figure 2 shows that research produced by researchers at universities in Africa has not only increased in terms of absolute numbers, it has also made progress in terms of its academic impact. In other words, more of the research published by scientists from Africa is being cited by their peers.

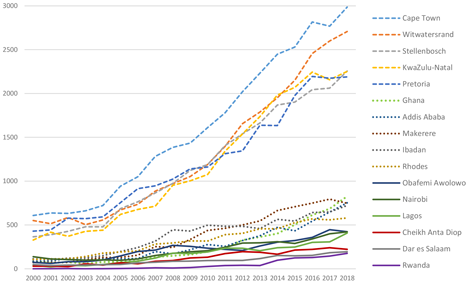

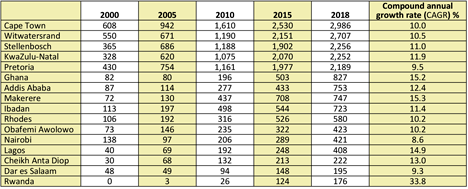

It is possible to disaggregate the data in figure 1 to reveal the publication performance of individual universities in Africa. Figure 3 shows data for the 16 universities that are members of ARUA, the network set up in 2015 to “enhance research and graduate training in member universities”. Figure 3 and Table 1 show the number of research publications produced at all 16 universities, with clear differences in the number of publications and in the growth in publications over time (Table 1). It is also apparent that many universities started to improve their publications’ performance from a very low base in 2000.

At first glance, three clusters of universities appear in Figure 3: (1) those with research publications in excess of 2,000 per annum; (2) those in the 500 to 1,000 range; and (3) those below 500 publications per annum in 2018. What Figure 2 does not show is how many academics each university employs and, consequently, how many publications each university produces relative to the size of their pool of researchers.

To illustrate, Rhodes University in South Africa is in the group that produced 500 to 1,000 publications in 2018. It is somewhat dwarfed by its South African peers. When the number of permanent academic staff is factored in, Rhodes compares favourably with KwaZulu-Natal, both producing 1.54 publications per academic staff member in 2018, while ‘outperforming’ Cape Town (1.51) in efficiency terms. While it is possible to reach this level of analysis for universities in South Africa, it is not possible to do the same for many of the other ARUA universities. The data is either not available, does not exist, or, if it exists, is available only for certain time periods that run parallel to the duration of one-off projects that collected the data.

Does Africa need more prophets or more engineers?

Figure 3 and the data currently available does not help organisations that may be more interested in funding a highly efficient instead of a highly productive university. Similarly, there may be interest in funding only particular areas of scientific research, for example, those aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals.

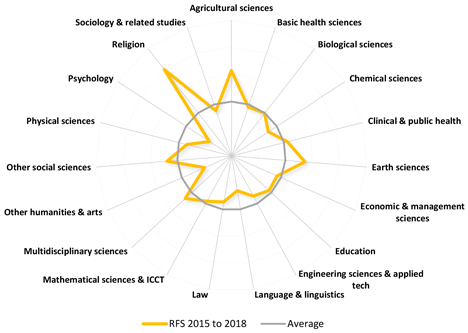

Figure 4 shows areas in the scientific endeavours of scientists in Africa that enjoy relative strength over the endeavours of their global peers. The graph shows strength in religious studies, agricultural sciences and earth sciences.

It also shows relative weakness in psychology, chemical sciences and language, engineering and linguistics. Funders of science may use the data in Figure 4 to identify areas of strength that are deemed to be in need of further investment, or they may use the data to correct apparent weaknesses.

There is a widespread belief that, in order to realise Kofi Annan’s dictum that universities should be at the core of development in Africa, the focus should be on STEM.

Figure 4 shows that the performance in STEM fields are not above average apart from agriculture and earth sciences. While it is certainly important to strengthen the STEM fields, it could be argued that Africa’s main challenge is in the social sciences, particularly governance. Combining religion with STEM is not going to make Africa a more competitive and developed continent.

From aid to partnerships

Collaboration between scientists in Africa and their international peers is seen as crucial for the development of research in Africa and to provide a diversity of perspectives and approaches from the developing world. Such collaboration is supported by equitable partnerships between universities and science organisations in Africa and those outside of the continent.

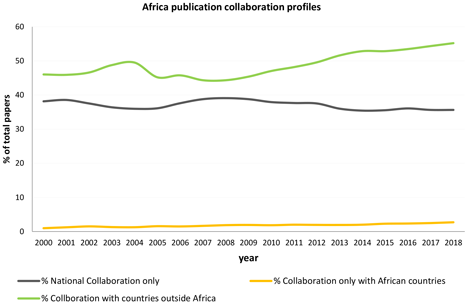

We have assigned each publication from Africa to one of three classes of collaboration: (1) national collaboration only: these are publications where all authors are only affiliated to organisations within the same country; (2) collaboration only with African countries: these are publications where authors are affiliated to organisations in different African countries, but no author is affiliated to an organisation outside the African continent; and (3) collaboration with countries outside Africa: these are publications where authors are affiliated to organisations in one or more African country and authors are affiliated to organisations in countries outside the African continent.

Figure 5 shows that collaboration between scientists from Africa and those from outside the continent has been increasing over time.

Collaboration increased from 46% of scientific papers co-authored with scientists from outside Africa in 2000 to 55% in 2018. Collaboration between scientists within Africa has remained relatively low and we see only a small increase from 1% in 2000 to 3% in 2018.

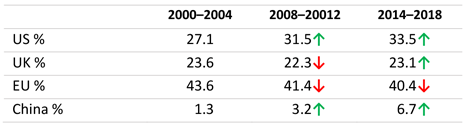

Table 2 shows collaboration at a regional level, that is, between Africa and four regions in the world, for three periods. The data shows growth in collaboration between scientists in Africa and China at the expense of collaboration between scientists from Africa and those from Europe (excluding the UK). It also shows that, if the UK had remained part of the EU, it would be by far the most collaborative region with Africa.

Concluding thoughts

The data presented above begins to provide a fuller account of the research landscape. But it does not tell the full story. There is, for example, increasing momentum in investments in centres of excellence on the continent.

There are at least 75 such centres of excellence at universities across Africa. The World Bank alone has committed to investing more than US$580 million to support these in Africa. ARUA and the Guild of European Research Universities are moving towards a ‘centres (or clusters) of excellence’ model as its preferred instrument for improving collaboration.

And yet, at present, there is little by way of data or evaluative frameworks to assess the performance of these relatively novel organisational structures at universities in Africa.

Missing also is data about other types of research outputs such as masters and doctoral graduates, that is, those on whom the future of the academy depends. Postgraduates are important role-players in the shift from resource-dependent to knowledge-driven economies.

According to a recent Bloomberg report, the proportion of communications companies in Africa’s total market capitalisation rose from 13% in 2010 to 29% in 2020.

During the same period, the share of materials and energy shrank from 34% to 23%. This could, it suggests, be an indication that Africa is growing away from its debilitating dependence on raw commodities.

Africa not only needs more scientific research, but it also needs highly skilled graduates to develop the continent. To reiterate the point made earlier: regular, reliable and comprehensive data on research universities in Africa is needed, as are more data analysts, to ensure that the current interest and imminent decisions related to investing in the continent’s universities are well-directed.

François van Schalkwyk and Jaco Blanckenberg are post-doctoral research fellows at the Department of Science and Technology-National Research Foundation (DST-NRF) Centre of Excellence in Scientometrics and Science Technology and Innovation Policy (SciSTIP), Centre for Research on Evaluation, Science and Technology (CREST), Stellenbosch University (SU), South Africa. Professor Nico Cloete is higher education research professor at the DST-NRF SciSTIP at SU. Professor Peter Maassen is a professor of higher education research at the University of Oslo in Norway and extraordinary professor at the DST-NRF SciSTIP, SU. Professor Johann Mouton is the director of CREST and of the DST-NRF SciSTIP, SU.

This article is republished from University World News – read the original article.

Figure 1: Africa’s scientific output is increasing

Figure 2: Africa’s scientific output is becoming more influential

Figure 3: The top research universities in Africa are increasing their scientific productivity

Table 1: Number of publications for selected years by ARUA universities

Figure 4: Science from Africa shows strength in religious studies, agricultural sciences and earth sciences

Figure 5: Collaboration between scientists from Africa and the rest of the world has increased

Table 2. Scientific collaboration between Africa and China is increasing