2 October 2018

Robert Tijssen and Jos Winnink

The 21st century world of science is still a very unequal world, dominated by the advanced economies in the ‘Global North’ with sophisticated science systems: this is where the vast majority of scientific research is done and where most of Nobel prize laurates did their breakthrough discoveries. Being among the best in scientific research is generally not seen as the hallmark of science in the less developed countries of the ‘Global South’. Yet, as this blog post will reveal, the South is steadily improving its contribution to ‘global research excellence’.

Our bibliometric data, extracted from processing hundreds of thousands of research publications, is effectively the sole source of quantitative information to tackle big questions like the one we are interested in: has the Global South become more ‘excellent’ in recent years? In our case, we data-mined the Web of Science database (WoS) at CWTS, where we selected all ‘research articles’, ‘letters’ and ‘review articles’ with at least one author address referring to our own delineation of the ‘Global South’: any country within Africa or South America. Getting published in a WoS-covered journal is often a mark of international quality for researchers working in resource-poor countries, especially those publications that appear in the ‘North dominated’ highly-cited scholarly journals.

Teasing out the role of globalisation in 21st century science, we split our set of research publications according to the clearly visible presence/absence of transcontinental research cooperation partnerships. Publications from authors in either Africa or South America that also have at least one address from a co-author located outside the continent were tagged as ‘Global South – transcontinental cooperation’. The vast majority of these cases involve some kind of research collaboration with countries in the Global North.

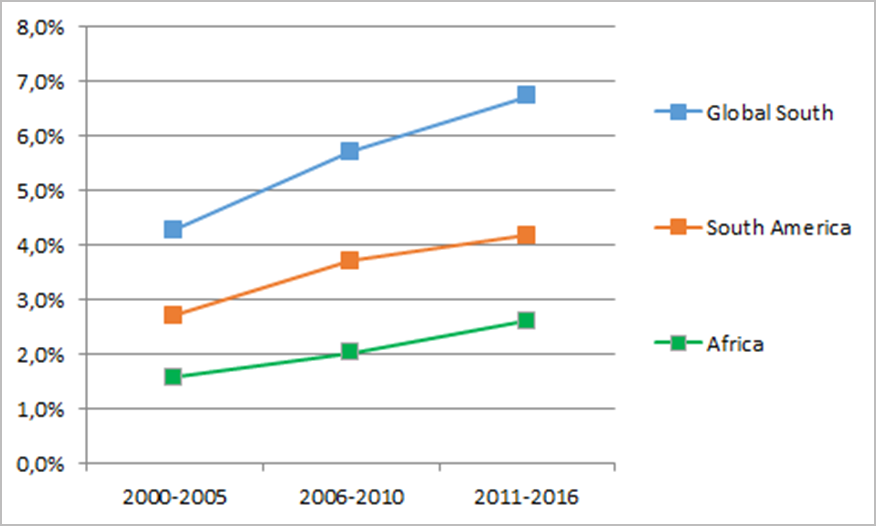

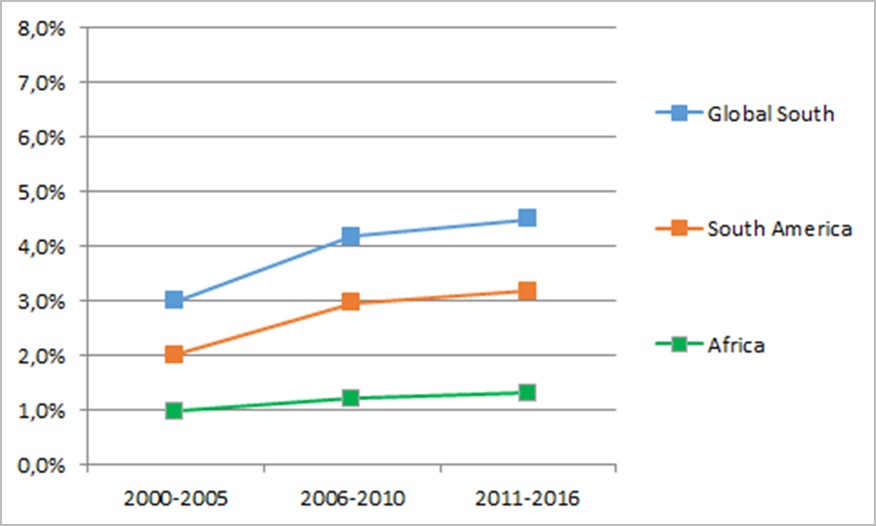

Graph 1 reveals that this simple and straightforward geographical divide produces quite significant results: discarding cases of transcontinental cooperation more than halves the share of African research on the global research publication output, which goes down from almost 3% to slightly more than 1%. The major effect of internationalization raises important issues on how science in the South should be perceived, defined and delineated. As Linda Nordling, an African science writer, features in her comment piece, ‘What is Africa’s real share of global science?’, the key question is: Should we take an ‘isolationist view’, discarding the role of international research partners, or is it more appropriate to adopt an ‘integrative view’ where such partnership are regarded as an integral part of a country’s science system? Both perspectives are of course informative. And the good news is that, irrespectively of the vantage point, the publication share of Africa and South America is increasing as we move further into this century.

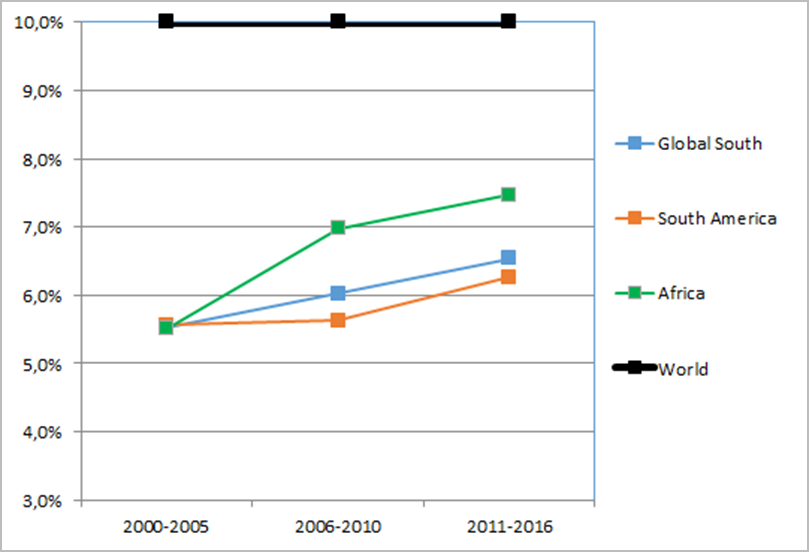

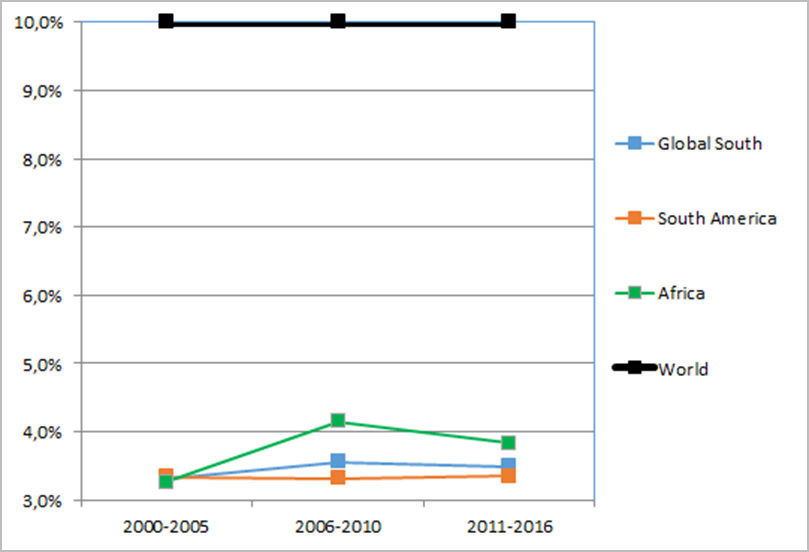

As far as the comparative measurement of research excellence goes – publishing is good, getting cited is better. Your publications being cited by scholarly peers is not only a clear sign of international visibility, it also tends to be regarded as a major achievement, and one of the indicators of research excellence, when your (joint) work is among the most highly cited in your field of science. Graph 2 examines the trends for the share of the publications from the Global south that are among the 10% most highly cited in their field. Although the Global South has significantly improved its performance on this excellence indicator, Africa in particular (see the left hand panel), we find a pronounced negative effect when removing the publications that involve transcontinental cooperation (right hand panel). The share of the Global South’s publications that are among the world’s most highly cited publications drops from 6.5% to 3.5%, and we find no measurable improvement during the last 15 years. Achieving research excellence in the South, in terms of high-end international citation impact, seems to rely heavily on research partners in the North.

The topic of research excellence in the Global South is moving up on science and innovation policy agendas – partially because of national economic development initiatives, partly as a result of internationalization trends in science. This millennium has seen a flurry of initiatives sprung up across Africa, and elsewhere in the Global South, where newly created centres of excellence are often funded or supported by organisations and charities in the North. More recently, in 2016, science granting councils in Africa have initiated a dedicated project, with a series of academic research publications and policy briefs, on this topic. The shared goal of these excellence initiatives is to enhance the visibility, quality and public value of science in the South. However, the ambitious concept ‘excellence’ tends to be both ambiguous and contentious. Its increasingly widespread application tends to meet a fair dose of scepticism. As Linda Nordling argues in a second commentary: ‘Excellence: what is it good for?’. To resolve such legitimization issues a distinction between ‘global excellence’ and ‘local excellence’ may provide a more appropriate perspective for policy frameworks, where Africa should set own standards of research excellence.

Although our macro-level bibliometric study taps into a huge reservoir of reliable empirical observations, the observed patterns and trends are still crude approximates that cover only a fraction of the wide range of research activities and outputs of the Global South. Publications and citations represent real life phenomena, but are very much a partial reflection of complex realities. Moreover, framing and interpreting publications and citations in terms of ‘global research excellence’, a fuzzy and multidimensional concept that is almost impossible to pin down and operationalize in any generally acceptable way, will always require cautionary interpretation. Nonetheless, looking through our ‘big data’ analytical lens, the main message is clear: research excellence in the South is gradually on the way up, aided by partners and their funding from the North.

This blog post is a result of our activities within ‘STI analytics for Africa and developing countries’, a research line within CWTS’ ‘Science, Technology and Innovation Studies’ program and our contributions to the research project ‘Research Excellence in the Global South’ within the South African DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Scientometrics and Science, Technology and Innovation Policy.

Graph 1: Share of Global South in worldwide research publication output: including transcontinental cooperation (top) versus excluding transcontinental cooperation (bottom)

Graph 2: Share of Global South in the world’s top 10% most highly cited research publications: including transcontinental cooperation (top) versus excluding transcontinental cooperation (bottom)