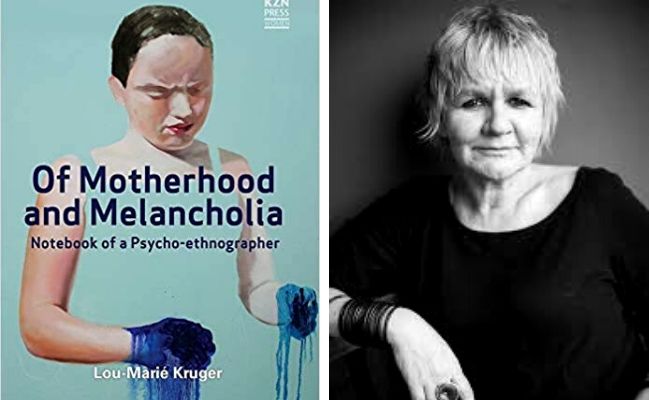

Of Motherhood and Melancholia: Notebook of a Psycho-ethnographer.

Lou-Marié Kruger.

Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2020. 382 pp.

ISBN 9781869144340.

In Of Motherhood and Melancholia, psychologist Lou-Marié Kruger sets out to give an account of the complex realities and lived experiences of low-income mothers in post-apartheid South Africa. The book covers two decades of clinical and research encounters in the Dwarsriver Valley, a semi-rural community outside Stellenbosch in the Western Cape. It is organised around the themes of home, labour, love, work, food, pleasure, illness and death (the ordinary aspects of life that “become brutal” [8] in the valley). Instead of a conventional academic treatise coolly delivering facts and conclusions, the reader finds a text almost literary in form, often fragmented and poetic, filled with anguish and doubt. “Feel my hands—they are always wet” (1) the prologue starts. A work that is birthed with difficulty, questioning its own being-there at every juncture. “I try to write the book. I cannot finish it” (11).

Kruger makes the difficulty of writing this book a central theme of the text, rendering the limitations of her project transparent to the reader (casting off the protective layers of obfuscating academic language and the scientific pretence of objectivity). The cause of her paralysis is far from unique: it is “the problem of white writing” (15). As “yet another white woman trying to write South Africa”, a middle class academic attempting to make sense of the slow violence of racialised poverty, Kruger is “[l]ocked into [a] hierarchical position” from where “writing seems to be an impossibility” (15).

In the beautiful and almost haunting style that becomes characteristic of the text, Kruger articulates this problem metaphorically and symbolically when she unpacks the meaning of the name of the Dwarsriver Valley—a valley “across or cross the river” (253). To get there from the affluent, leafy town of Stellenbosch (“that green hell” [15]) where Kruger lives, she must drive through the Bange Kloof, “a tremendous passage”, a “valley of fear” (12). “I decide my book is about

passages—of pregnancy, of childbirth, of motherhood, of healing, of becoming a psychologist” (13), she writes.

A book of liminality, thresholds, and margins. The hierarchies and borderlines that Kruger finds herself locked into and is trying to write across, are not only between white and black, rich and poor. In her clinical encounters and research interviews she also runs up against the rifts between researcher and research subject, mind and body, observation and engagement, self and other, agency and disempowerment, among many others.

From a feminist philosophical perspective Kruger’s work on motherhood takes on radical symbolic significance, because of its commitment to the liminal. In her famous rereading of Plato’s Cave Myth, French feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray argues that the Western symbolic order is founded on a forgetting or a burial of the (m)other, represented by the cave (the matrix/womb) which the prisoner leaves behind to move toward the Sun/Idea in an erasure of material beginning. The forgetting of the “path that links two ‘worlds’” leads to the “founding” or “hardening” of all “dichotomies, […] all the confrontations of the irreconcilable representations” (Irigaray 247). The result is that difference is constructed as opposition and hierarchy, so that the world is broken up into an endless range of binaries like mind/body, culture/nature, self/other, subject/object, where the second terms are less-than and coded feminine, serving as negative foil for the emergence of the primary terms, coded masculine.

The work of scholars like Oyèrónké Oyĕwùmí shows how this sacrificial logic is not only at the basis of patriarchy, but also structures the racial project of colonisation, where blackness (similar to and intersecting with femininity in relation to masculinity), becomes the negative foil for whiteness and where the hierarchical dichotomy of white/black is mapped onto the dichotomies of human/non-human, spirit/matter, present/past etc. Understood in this way, the intersecting work of feminism and decolonisation requires the undoing of the murder of the (m)other through restoring the forgotten relationship or path:

“Between … Between…. Between the intelligible and the sensible. Between good and evil. The One and the many. Between anything you like. All oppositions that assume the leap from a worse to a better” (emphasis in original) (Irigaray 47–8).

It is this difficult symbolic work that Of Motherhood and Melancholia is engaged in when it commits to thinking in terms of encounter and relation (rather than opposition and hierarchy). Notable here is the book’s consistent and creative undermining of what might be the central dichotomy in the discipline of psychology and our established academic processes of knowledge production, namely mind versus body (closely connected to self versus other). “Fuck psychology and fuck research”, Kruger thinks when the rules of infant observation prohibit the researcher to hold the baby “as if observing is not a form of interaction” (29).

Especially striking in this regard is the chapter on hunger, which Kruger starts with the question: What does it mean to be hungry? (155). “Psychologists do not know what to do with hungry people” (157). The idea of hunger conjures up “an open mouth, lips, teeth, tongue” and “[a] naked bony body with bones, an anorexic girl, kwashiorkor or an obese man,” she writes (157).

However, “always, implicit in hunger is also desire (the desire to eat, to be loved, to be nurtured)” (157). When she thinks about this kind of hunger, she is “not only thinking about the too-skinny, blonde, straight-haired girls” that she encounters in the context of her private practice in Stellenbosch, but also about “the desolate women standing in line for the unpalatable mix-up in the soup kitchen, the school kids who are hungry on Mondays, the many young women who crave a baby, Wilmien Wilders who wants a job, the Wolf Man who dreams of being mouthless, and Dora whose hungry children make her crazy” (173–4).

Kruger’s commitment to thresholds and passages leads her to turn to literature, metaphor and narrative as main register or lens through which to approach and give expression to her work in the valley. By foregrounding the narratives of the mothers, interspersed with journal entries as well as fragments of Beckett, Kamfer, Neruda and Szymborska (among many others), the book becomes “an indirect critique of how the poor and the ‘slow violence of poverty’ have been (mis)represented and systematically obscured in academic writing, albeit inadvertently” (9). Kruger’s own writing is rich, poetic and layered, with some passages so startling in their detail, depth and beauty that the reader pages back, sometimes more than once, to read it again, slowly. Through this turn to narrative, the text holds space for seemingly opposing worlds to exist in relation to one another, for ambiguity and paradox to be generative rather than corrosive of meaning—a defiant gesture against the symbolic matricide at the foundation of the colonial patriarchy that continues to structure our world. In Motherhood and Melancholia, the reader encounters not only the (m) others of the valley, but always also and again, herself.

Works Cited

Irigaray, Luce. Speculum of the Other Woman. Trans. C. G. Gill.

Cornell U P, 1985.

Oyĕwùmí, Oyèrónké. The Invention of Women: Making an African

Sense of Western Gender Discourses. U of Minnesota P, 1997.

Azille Coetzee

azille.coetzee@gmail.com

Stellenbosch University

Stellenbosch, South Africa

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3948-1249

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17159/2309-9070/tvl.v.57i2.8504

Buy the book here:

https://www.bookdepository.com/Motherhood-Melancholia-Lou-Marie-Kruger/9781869144340